Tunnells Philippe Cini on Pharma Operational Excellence

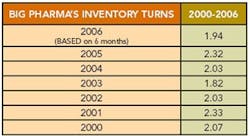

Editor's Note: A few months ago, we had calculated a “Lean Index” for pharmaceutical manufacturing based on inventories and cost of goods sold. We learned that most pharma companies appeared to be running inventory turns of 2 or less (Figure 1, below).

As a “reality check,” we spoke with Philippe Cini, Ph.D., vice president of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Services at Tunnell Consulting, for his views on pharma operational excellence programs, and the roles that PAT and Quality by Design should play. Lean is important, Cini says, but reducing the cost of quality represents a significant financial opportunity, much greater than reducing inventory levels. He spoke about these issues late last year, at a conference in Toronto.

What follows is a conversation with Cini on PAT.

PM — What is the best way for drug companies to measure true operational excellence? Is inventory turns a good metric, or is it too simplistic?

PC — The best approach is not to use one metric, but to take a balanced scorecard approach, using 5 to 10 different metrics to ensure that your performance is adequate. The word “balanced” is very important because you don’t want one metric to be so good that it offsets another. Consider inventory levels, for example, they cost money and many manufacturers want to reduce them as much as possible. But if they are reduced too much, it will result in shortages of needed products and poor customer service. Organizations need to set some equilibrium, some intermediate optimum level.

Within the plant, another good metric of use is how much of the product was “right the first time”; this is a good measure of quality. On a more granular level, you want to track number of deviations and number of investigations, number of rejected batches.

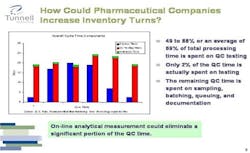

Figure 2. Click chart for larger image.

PM — How is the drug industry doing, overall, in terms of its “balanced score card?”

PC — Performance varies, but as a whole, it’s fair to say that companies with typical drug company metrics could not survive if they were operating in another industry with lower profit margins such as the chemical industry.

Figure 3. Click chart for larger image.

Because of high demand and high margins for its products, pharma still forgives some inefficiencies. However, the industry could significantly increase its current inventory turns if it were to change the technologies it uses and the way it approaches its overall supply chain.

For example, more manufacturing processes could be converted from batch to continuous. The supply chain could be redesigned to a “push/pull” model, in which one manufactures to a forecast to a certain point, then, in pull mode, make product to order, thus reducing inventory and increasing responsiveness to changes in the market. For such a model to become feasible, cycle times need to be compressed and information flow needs to be improved.

PM — Which are the best models from outside pharma?

PC — Consider Dell, which uses modular equipment. It makes a certain amount to stock, but uses modular equipment to make a finished product, and its inventory turns are over 90. If pharma can start mimicking this approach, it will be able to improve its inventory level situation. Of course, constraints must be in place for life saving drugs, where FDA sets specific requirements to protect the public from sudden shortages.

PM — Within pharma, which companies are the best Lean models?

PC — More companies are adopting Lean/Operational Excellence programs. J&J and BMS both have such programs that are well developed. They are not the only ones.

PM — Where are the most significant savings to be made in pharma OpEx today?

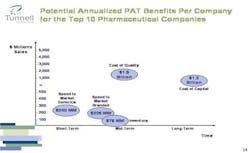

PC — There’s no question that reducing inventory is important and could save large pharmaceutical companies tens of millions of dollars. This is the order of magnitude we calculated.

However, the real savings come from reducing the total cost of quality.

Figure 4. Click chart for larger image.

If one were to implement a quality improvement program based on the principle of Right First Time, our calculations indicate that each one of the top 10 pharmaceutical companies would find that the inefficiencies in quality cost on average $1.5 billion, providing a much more dramatic opportunity for improvement.

Figure 5. Click chart for larger image.

If I were a CEO, I’d pay a lot more attention to the cost of quality. Inventory savings in the neighborhood of $100 million are good, but they aren’t enough to change the fate of a company.

PM — What is your view on PAT and its acceptance by pharma to date? We see more companies evaluating it but, PAT hasn’t yet become an established way of doing things yet.

PC — It hadn’t been positioned very well, and was promoted by technical people who didn’t speak the same economic language as the executives. The new paradigm being advanced by FDA, Quality by Design, encompasses PAT but offers a broader framework. Executives can understand it more readily and is likely to gain traction more rapidly than PAT alone did.

PM — Are pharma companies using operational excellence tools as fully as they might?

PC — In general, use of these tools is far from uniform. Some companies use them very well and consistently across the entire organization and some don’t.

PM — Is training the main problem?

PC — It is clearly a need. Greater capabilities in process engineering, quantitative analysis, operations management, lean techniques would benefit the industry.

PM — Will the current mantra of reduced spending have an impact on operational excellence within the industry?

PC — It should, as the need for improved efficiencies will increase.

PM — But won’t downsizing impact PAT?

PC — Downward cost pressures are likely to impact PAT programs and any other program for that matter for which the benefits case is not clearly articulated. As I indicated earlier, we have not spent nearly enough time collectively trying to quantify that value. On the other hand, it is my impression that the QbD framework and the value derived from it are more easily understood and accepted by Pharma executives. In a way, PAT paved the way for QbD.

PM — You’ve already described how PAT shouldn’t be defined. How should it be defined?

PC — What PAT really means is being able to understand your processes and control them more tightly and efficiently. As references, there is the PAT guidance document, but also now ICH Q8, and the Quality by Design initiative.

ICH Q8 introduces the notion of Design Space, Critical Process Parameters and Critical Quality Attributes. Importantly, it describes the regulatory flexibility that the Design Space avails.

PM — You had mentioned continuous manufacturing. Can this become the norm for pharma?

PC — It’s already a reality in some cases, but still isn’t common. For example, consider blending in manufacturing suites. The cost of operating these blenders is huge, because each one spends a lot of time either being cleaned, inspected or idle.

The technology to feed and blend continuously already exists. Imagine using a small cyclone in a continuous way as opposed to a large blender in a batch operation. The capital expenditure would be drastically reduced.