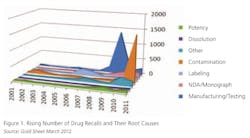

The last few years have seen an increase in drug manufacturers’ failures to follow current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) consistently. This year’s numbers have not yet been released by FDA. But last year, the number of cGMP-related drug recalls increased substantially, exceeding a record set in 2009 (see below).

|

Contamination Drives Spike in Recalls, Warning Letters in 2011 By Bowman Cox, managing editor of "The Gold Sheet" Contamination issues drove drug recalls to record levels in 2011 and contributed to yet another increase in FDA warning letters that year, according to analysis by “The Gold Sheet,” a publication from Elsevier Business Intelligence that focuses on drug manufacturing quality. Analysis of this year’s recalls and warning letters will appear in “The Gold Sheet” early next year. RECALLS As in 2009, most of the spike was from a single repackaging incident. Much of the rest was from potentially contaminated antiseptic swabs, pads and wipes sold by H&P Industries Inc., Hartland, Wis., and distributed through its Triad Group Inc. unit. Of last year’s 2,329 drug recalls, 1,024 resulted from a single incident, in which Aidapak Services LLC, Vancouver, Wash., realized that penicillin could have cross-contaminated numerous products repackaged in its facility. The incident mirrors previous repackaging failures that inflated recall numbers in 2000, 2006 and 2008. Aside from the Aidapak and Triad recalls, there were another 248 contamination-related drug recalls in 2011, still four times the prior decade’s annual average. Of those 248 contamination recalls, 33 involved issues related to glass containers such as cracked syringes or the presence of glass flakes. Another 10 involved malodorous plastic bottles tainted with 2,4,6-tribromoanisole (TBA), a degradant of the chemical wood preservative 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP). There were also a number of cases involving foreign tablets, a few involving precipitation or crystallization, and a variety of cases of particulate contamination of injectables involving stainless steel, polyvinyl chloride, rubber and food grade gasket materials or unspecified materials. Injectables recalls were three times the prior 10-year annual average due to the same combination of factors that drove them to record levels in 2010 and that have contributed to shortages of critical drug products. There was a huge increase in warning letters to injectable drug manufacturers in FY 2011, which corresponded to the increase in recalls for injectable drugs. FDA inspections also found more problems with sterility assurance for injectables. The number of warning letters going to injectables manufacturers shot up from four in FY 2010 to 13 in FY 2011. Also, FDA inspections last year identified more problems in the global supply chain. Of the 52 warning letters issued in FY 2011, 17 went to active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturers, up from eight in FY 2010. An analysis of the 52 warning letters by “The Gold Sheet” found that production record review, which includes batch failure investigations, was the most common deficiency cited during the last fiscal year. This deficiency was noted in 28 of the 52 warning letters issued, or about 54 percent. The increase in warning letters going to sterile drug manufacturers is reflected in the higher number of deficiencies noted in the microbiological controls area. The full analysis of FY 2011 FDA recalls and warning letters is available at the elsevierbi.com website. |

Both Warning Letters and recalls of injectables were notably higher, with injectable recalls three times the 10-year annual average reported two years ago, according to Bowman Cox, managing editor of “The Gold Sheet,” which analyzes and reports regularly on FDA data.

“We’re seeing the same types of failures we saw in the early 1980s, when nearly 70 percent of ethical pharma was under Warning Letter or Consent Decree,” says one consultant, who asked to remain nameless.These compliance failures have far-reaching effects, not only on corporate reputations and bottom lines, but also on patients. In discussions earlier this summer between FDA and members of U.S. Congress, manufacturing noncompliance was noted as a key reason for chronic shortages of important drugs, including injectable anesthetics and cancer treatments.

According to Jeanne Ireland, FDA’s Assistant Commissioner for Litigation, who detailed facts in a July letter to Elijah Cummings on the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, this year, quality control issues at drug manufacturing facilities continue to account for shortages of drugs, particularly injectables. Last year, manufacturing issues, including QC problems, resulted in nearly 70% of shortages.

Consider the critical anesthetic injectable Propofol. Serious contamination issues at its manufacturer’s, Teva Pharmaceutical’s facility in Irvine, Calif., led to a shutdown of the facility, resulting in chronic shortages. The plant was reopened this spring.

Problems involved endotoxin contamination of Propofol emulsion. The company had failed to test for endotoxin in its lot samples, had been unable to find the reason for out of trend results in endotoxin level, and failed to maintain cleaning and sterilization equipment effectively, FDA said.

In this brief overview, observers and experts share insights into some of the industry’s most chronic recurring cGMP noncompliance areas, citing lessons that manufacturers might learn for the future. Some consultants refused to be interviewed, while others asked to remain anonymous because they work with some of these manufacturers to help them resolve these issues. However, the companies and the problems involved are in the public record.

What’s notable, one consultant says, is the fact that many of Big Pharma’s recent cGMP failures have involved fundamental quality principles and are coming from companies that know better. “Many of these companies were the shining example of compliance in their day,” he says.

Among the most glaring recurrent problem areas that FDA inspectors have noted (sidebar) is a failure to validate processes. In addition, many drug manufacturers today are inconsistent in documenting or systematizing QC operations, says Ken Reid, publisher of “Validation Times and Food and Drug Inspection Monitor,” both of which track FDA enforcement activities very closely. There is also frequently a failure to establish adequate laboratory controls or to get to the root “out of specification” (OOS) problems, he says.

Former FDA inspector Dennis Moore, now managing partner of AUK Technical Services, has seen this misunderstanding of Quality Systems first hand. During a recent visit to a company with a good compliance record and sophisticated approach to quality, Moore asked for a copy of the company’s Quality Policy, and, at one site, was presented with 20 different versions.

Pharma is still at a relatively early evolutionary stage in its quality and risk management systems, said Mike Long, Director of Consulting at Concordia Valsource, during a November webcast. In addition, Moore says, many companies are using HAZOP for risk management, but driving processes to their critical control points. This can lead to turf battles over which process is more critical. He suggests that drug manufacturers embrace the modern spirit of medical device quality management systems guidance. In fact, he says, ICH Q9 refers directly to this guidance and FDA inspectors are being trained in its principles.

| Top 10 Reasons Why Drug Manufacturing Plants Fail FDA Inspections 1. Failure to document, in writing, and/or follow QC responsibilities and procedures 2. Lack of process validation to assure proper identity, strength, purity and quality of drug 3. Insufficient laboratory controls 4. Lack of investigation into Out-Of-Spec batches, and complaints, or batch-to-batch variation 5. Insufficient GMP training and written procedures 6. Written SOPs and production procedures aren’t being documented and/or followed 7. Lack of written procedures for equipment cleaning and maintenance 8. Insufficient cleaning and maintenance 9. Lack of testing to assure the specs of API 10. Lack of in-process monitoring of critical process parameters that validate the performance of manufacturing processes that might cause variability. Source: Sharon Toma, FDA Inspector, ORA from a presentation at the International cGMP Conference, March, 2012, summarized in Validation Times, March 2012 |

Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) programs, and failure to trace patient complaints in the field continue to dog manufacturers, based on a cursory look at FDA enforcement records. As Rick Friedman, Associate Director of FDA’s CDER’s Office of Manufacturing and Product Quality has said, manufacturers still emphasize the C in CAPA, when they need to focus on the P. It was just this failure to investigate serious adverse effects in patients that led to the inspection and closure of Teva’s Irvine facility.

CAPA is never directly spelled out in the cGMP code, says Moore. He suggests that drug manufacturers refer to the QSIT guidance on FDA’s website, as well as ISO 14971, both of which are medical device-oriented, for best practices.

Winners and Sinners?

When asked for examples of proactive corporate quality systems, consultants cited biopharmaceutical manufacturers as the best examples. Biopharma has had its problems with contamination, which led to one recent consent decree at Genzyme’s Allston facility. However, one consultant says biopharmaceutical manufacturers are generally more proactive about compliance and quality. He cites Genentech’s use of intermediate modeling and design of experiments to ensure process understanding when compounds reach commercial stage. He also mentions Amgen, which is currently studying how to use ASTM 2500 in qualification and validation efforts.

Another consultant praises Abbott’s approach to CAPA. At least before the restructuring, he says, the company used one standard CAPA system for its multiple product lines. In most cases, he notes, pharma companies are using different systems, or developing their own homegrown approaches, which can lead to confusion.

There are no real “winners” and “sinners” in this story. Today’s sinners are often the compliance models of the future. But here are some case studies in compliance from FDA’s recent inspection and enforcement records:

• Novartis

The company’s recent GMP problems showed a failure to investigate consumer complaints of foreign products in its oral solid dosage forms. There were more than 160 such complaints since 2009, but a root cause was never found. The company also failed to extend investigation into all potentially affected product batches. In addition, FDA noted that complaint investigations took up to 100 days, and there was no attempt to retrieve suspect material from the marketplace.

There was a mixup in packaging so that the wrong product was placed in the wrong package. “Line clearance is a core quality element of any manufacturing organization,” says an anonymous consultant. There were also failures to address root causes of contamination and repeated analytical and procedural failures.

• Johnson and Johnson

Three sites move toward remediation since being cited by FDA. All three were cited for failing to investigate complaints and establish root cause of quality problems.

• Hospira

The company’s Austin and Rocky Mount facilities received warning letters for problems with injectables, CAPA and sampling.

• Ben Venue

The company’s Bedford plant recalled 10 products due to sterility assurance problems, particulate contamination and low-fill volume. In addition, the company was sited for poor maintenance, staff training and building problems such as mold.

• Sandoz Canada

Crystalline material was found in sterile injectables; foreign matter and broken tablets were found in opiate products produced in Nebraska.

As one consultant points out, these failures aren’t intentional, but may reflect corporate cultures where greater value is placed on the creation and dissemination of systems and processes, rather than the content of these systems. “CEOs can talk the talk, but if they do not reinforce the concept that high quality will ultimately equate to bigger and better profits, it is just lip service,” he says.

Editor’s Note - Pharmaceutical Manufacturing will be increasing its coverage of compliance in 2013, and will also be launching a new e-newsletter focused exclusively on this area.

References

QSIT Audit Guide Summary

Kerr, M., ISO 14971 and ICH Q9