Many products released to the market that are used on a daily basis are not required to be sterile. Examples include over-the-counter medicines, creams and supplements to name a few. The microbial quality of these products is ensured because the manufacturers are required to evaluate the microbial content of each product. To accomplish this, Microbial Examination of Nonsterile Products is performed. This test, formally known as the Microbial Limits Test, determines the bioburden of the product and also if objectionable organisms are present. On May 1, 2009, the harmonized test method became effective, requiring manufacturers to meet the new guidelines set forth in it.

For manufacturers, it is critical to understand how the recent harmonization of the USP, EP and JP requirements affects the processing of raw materials and finished products. It’s also essential for manufacturers to be well aware of the considerations to examine when establishing a microbial limits testing policy.

AFFECTS OF HARMONIZATION

The harmonization of this test made some major changes to the USP requiring manufacturers to evaluate their testing plan and products in order to meet the newer requirements. One of the major changes was the splitting of the older test, contained in USP <61>, into two tests now contained within USP <61> and <62>. The testing discussed in USP <61>, Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Tests, covers the examination of a product to determine the microbial content. In contrast, the testing covered in USP <62>, Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Test for Specified Microorganisms, sets forth the methods used to detect organisms that are considered objectionable. These two tests make up the referee test used to determine if a product meets your established specifications for microbiological quality.

A benefit of the harmonization is that comprehensive single test can be followed to comply with the three pharmacopeias’ regulations. However, to accomplish this task, changes had to be made, which pose some challenges to manufacturers. The biggest change came in the addition of three microorganisms to the previous four that were contained in USP <61>. Tests for bile-tolerant gram-negative bacteria, C. albicans, and Clostridium species were added to the list of specific organisms now contained in USP <62>. The methods used to screen for E. coli and Salmonella sp. were also updated to conform to the other pharmacopeia.

Additionally, negative controls were added to the suitability and growth promotion tests. As a result of these changes, manufacturers will have to evaluate their testing methodologies to ensure they comply with the new guidelines.

A new requirement to confirm any growth detected during the test for specified microorganisms was added. Manufacturers may not have performed identifications before and may not be familiar with which method would be most suitable to use. The compendium does not speak of a specific method to perform these identifications. To help determine which method is best, it is important to understand the rationale for the ID. USP <62> is used to screen for specific organisms, therefore utilization of a technique capable of identification to the species level would be most appropriate. Today’s modernized PCR genetic identification techniques are best suited for this application because of their large libraries and accuracy.

When planning for these changes, one should keep in mind the scheduling implications of meeting the new requirements. Ensuring the test method is compliant with the new USP methods will require re-validation of the E. coli and the Salmonella sp. Additionally, one may need to validate the three organisms that were added to the USP. Performing identifications on growth detected during the <62> test will likely extend the turnaround time for the final results. These are all important factors that need to be considered when planning or evaluating one’s testing schedule.

Scheduling implications are not the only drawback to the harmonization of this test. There are fiscal concerns that arise considering portions of the test will have to be validated and that one may have to perform identifications during the testing. It is also likely that the price of testing may have increased because of the changes that were made during harmonization. These may not have been planned for in an original testing budget, so supplementary funding may be required to cover these costs.

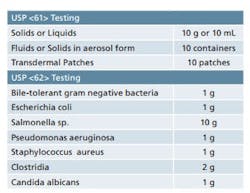

Sample requirements for Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products as per USP <61> and <62>.

One final consideration that needs to be addressed is the availability of sample. If established sampling plans are in place, the availability of product may be limited. Due to re-validations being required for some parts of the test, additional sample may be required. This may involve modification of your current sampling plans to ensure that there is sufficient product available for testing.

SAMPLE REQUIREMENTS

It is important to ensure that adequate quantities of product are available when you are developing your sampling plan. USP <61> and <62> detail the quantity of sample that is required for each of the tests contained therein. While the minimum quantities are provided in these chapters, it’s best to have some material on hand for any unforeseen circumstances. Table 1 provides a quick reference for the quantities of material that are set forth in the USP chapters. Final sample requirements will ultimately vary based on the number of organisms being screened and whether or not suitability work is required. Also note that there are some special sampling provisions provided in the guidelines that are not included in Table 1.

PROCESS

When a product is submitted for Microbiological Examination of Non-Sterile Products, USP <61> and <62>, the examination process is initiated with many steps being performed concurrently. The microorganisms that are used for the assay are cultivated and their populations are determined; this process is accomplished within a couple of days from start to finish. The current USP guidelines emphasize the need to use fresh cultures; therefore the microorganisms are grown and used within 24 hours of harvesting.

The required media for testing is procured and the quality of the media is assessed. To accomplish this, growth promotion tests, inhibitive properties tests and indicative properties tests are all performed on every new batch of media used. This ensures that each batch of media is capable of supporting or inhibiting growth of the microorganisms.

Stock sample mixtures are prepared using aseptic practices in a Class 100 Laminar Flow Hood or a Biosafety cabinet to avoid contamination of endogenous organisms. For microbial enumeration, USP <61>, appropriate volumes of the sample preparation are plated to Soybean Casein Digest Agar and Sabouraud Dextrose Agar.

USP <62> outlines methods used to encourage the growth of existing microbes present in the product that could go unnoticed without enhancing the organism’s growth. Therefore, the sample and suitable portions of the prepared sample stock solution are transferred to separate, appropriate mediums to begin the enrichment phase of the test. These mediums include, but are not limited to Soybean Casein Digest Broth, Sabouraud Dextrose Broth, or Reinforced Medium for Clostridia.

The initial sample-broth mixtures used for enrichment are then sequentially subcultured to selective media one or two additional times before final results are obtained and documented. Although the media used is relatively selective to the organism screened for, a positive result is confirmed using microbial identification methods.

If the product has not undergone suitability testing, then each of the challenge organisms are combined with the sample stock preparation to validate both USP test methods. Suitability Testing validates that the microorganisms will grow in the presence of the product. A satisfactory result indicates that the product does not inhibit growth of the challenge organism and the methods employed for testing have been appropriately designed.

SUITABILITY TESTING VS. VALIDATION

The USP requires that the testing method used is proven suitable for its intended purpose. The primary purpose of suitability testing is to establish that the product being tested does not have any adverse effects on the test, specifically inhibition of the control microorganisms. Some products may have antimicrobials or preservatives in them which could interfere with the detection of organisms. To demonstrate that there is no interference in the test, sample preparations are spiked with a known concentration of control microorganisms, incubated and the recovery of the microorganism is determined. If growth of each challenge microorganism is not inhibited by the product, then the method followed is deemed suitable.

There are two ways of showing system suitability differing primarily on the stage of product development. In the earlier stages of development, rather than performing the validation at this time, manufacturers may consider performing the suitability test with each new lot produced. The reasoning for this is because changes may need to be made during the development of a product which would, in turn, require re-validation. If a suitability test is performed after changes have been made to the product, it ensures that the test method used is still acceptable. This allows the manufacturer to maintain some level of flexibility while performing research and still certifies the quality of each product.

After a final product is manufactured and is ready for release to market, then a validation should be performed. According to USP <1227> a validation is performed on three independent lots of identical product. This should exhibit that the product does not interfere with the test method, while also showing that the method is repeatable between different lots of material. The benefit to this approach is that, after completion of the validation, the sample screening alone would be needed to release your product. A validation essentially locks the manufacturer into the final formulation of each product; therefore, if changes are made to the product, it would need to be re-validated.

ESSENTIAL PRODUCT INFORMATION REQUIRED FOR TESTING

Before submitting samples for testing, manufacturers should be prepared to answer several questions related to each product’s specific requirements. Although the answers to these questions are easily obtainable, an inability to provide them may cause delays in testing. Manufacturers should supply as much information about their product as possible to the testing laboratory to lessen delays in processing. Some of the information that should be provided will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

There are inherent differences in some products that require different means of handling. This is addressed in the USP by providing different methods for sample preparations based on which category the samples fall under. These categories are water soluble, non-fatty products insoluble in water, fatty products, fluids or solids in aerosol form and transdermal patches. Each of these categories has a different method to prepare the samples for testing. Therefore, it is important to know which categories each of your products belong to so they are handled properly during testing.

Manufacturers should also be prepared to provide the product’s Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS). The MSDS will be helpful to the testing laboratory when they are preparing to test the product. It contains important safety information about the product, including handling procedures, which will determine how the product is managed when tested. Also included in the data is solubility information that will assist the laboratory in determining how to prepare your sample for testing. Many laboratories will require an MSDS up front to determine if the manufacturer’s product is something they can work with safely. Being able to provide this information as soon as possible will help prevent costly delays.

Each product’s specifications are critical to assessing its microbial quality. In order to establish this limit, the intended use of the product needs to be considered as well as who the intended recipients will be. USP <1111>, Microbiological Attributes of Nonsterile Pharmaceutical Products, is a starting reference to establish a baseline criterion. However, a thorough risk assessment of each product should be conducted to determine if these criterion are adequate.

Sometimes additional objectionable pathogens should be considered. These are determined by how each product is manufactured, where the raw materials are sourced, the product’s intended use, and who the end-user will be. Is water associated with the cleaning of the system or used to make goods? Do the raw materials come from the America’s mid-west or a developing country? What is the intended use of the product? Will it be applied topically, orally, inhaled, etc.? What are the health hazards to the consumers? Are they immunocompromised? The aforementioned questions are only a few of countless considerations.

Objectionable organisms can come from an infinite number of sources. One critical area that can introduce objectionable organisms is the raw materials used in the product. Knowing the source of these components, location and physical source, will help in deciding if screening for additional organisms is necessary.

Materials sourced from regions that may not have adequate quality and environmental controls should be thoroughly examined for potential organisms that need to be screened for. Also, items that are sourced from animals or plants may harbor endogenous organisms that may be pathogenic to humans.

The production process can be a major source of contamination. Even with the best of controls, there will still be opportunities for contamination. Understanding your production process will help identify those potential vulnerabilities. Some steps of concern are those that involve compression and water. As these steps mix in-process material with outside resources there is a higher risk of contamination. Therefore, any contaminants present in these sources may be of concern. To aid in determining additional organisms of concern, an analysis of both the production process and environmental data can be beneficial.

Looking at infection trends and infection susceptibilities are also important when determining if additional objectionable organisms should be examined. Since your target recipient may be susceptible to certain infections, knowing who the product will be administered to is critical. It is important to note that not every infection will be of a concern. Infections would have to be examined along with the likelihood that your product will contain the pathogenic microorganism that could potentially cause such illnesses. Since some infections can only be transmitted via specific routes, the route of administration for each product should also be known.

When performing the product’s risk assessment, these are all questions that should be considered.

The intended recipient and the method of administration for each product are important factors when establishing the final acceptance criteria. Different recipient populations may require different acceptance criteria based on their ability to fight infection, age, and if any preexisting conditions exist. For example, if the product is used on neonates and infants, a more stringent criterion would likely apply because these groups have developing immune systems and are less capable of fighting infections. Likewise, if immunocompromised patients are the intended recipients, then a tighter criterion would also apply for the same reason. Other less obvious factors, such as preexisting diseases, wounds, or organ damage are important when establishing acceptance criteria. A thorough risk-based assessment should look at all of these factors when establishing the final acceptance criteria.

REFERENCES

<61> Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Tests

<62> Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Tests for Specified Microorganisms

<1111> Microbiological Attributes of Nonsterile Pharmaceutical Products: Acceptance Criteria for Pharmaceutical Preparations and Substances For Pharmaceutical Use

<1227> Validation of Microbial Recovery From Pharmacopeial Articles

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

James Gebo is a Technical Services Representative at Microtest Laboratories. He has hands-on experience in regulatory microbiology and virology testing since 2004. He holds a B.S. in Biology, a Masters in Public Administration, and is a Registered Microbiologist (NRCM). To contact Gebo directly: 413-786-1680 or [email protected].

Kimberly Kitch is a Laboratory Technician II at Microtest Laboratories. She has been employed by Microtest Laboratories since January, 2006 and has worked in a number of different areas, including but not limited to, Microbial Limits, Genetic Identification of Bacteria and Fungi, LAL/Biocompatibility, and Bioburden Testing. She holds an A.S. in Biology and intends to continue to pursue the field. To contact Kitch directly: 413-786-1680 or kkitch@microtest

labs.com.