Quality problems are rising in the pharmaceutical industry, often to the point of crisis. But remediation is no simple matter. If not handled effectively, it can be extremely cumbersome and expensive, often without even fully meeting its main goal: reducing patient risk. Delayed or ineffective efforts can also bring on drug shortages, which hurt patients and the industry as a whole — not to mention creating greater financial risk.

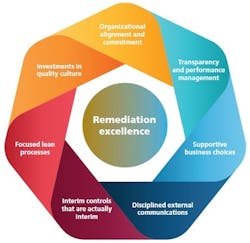

Exhibit 1: Successful companies have included seven key elements in their remediation programs

It’s time for companies to devote more attention to effective remediation initiatives. Empirical evidence demonstrates that an intensive investment early on, following a structured approach to problem solving and project management, can make remediation run much more smoothly. Indeed, properly managed remediation efforts can not only restore operations to normalcy, but also strengthen a company’s quality systems and operating culture to help forestall future crises.The good news is that companies entering a remediation can learn from those that have navigated their own quality crises. The leaders of those successful pharmaceutical companies have found ways to implement focused and time-sensitive fixes while laying the groundwork for better quality systems for the future. We’ve distilled seven foundational principles from the successes of those companies (Exhibit 1).

1. Align & Commit the Whole Organization

To ensure successful remediation, the entire organization must be committed to the effort. Typically, quality and compliance problems that are large enough to require remediation are complex, with root causes that are difficult to identify and resolve. Sophisticated solutions cannot be implemented solely by the quality staff or even the entire operations organization. Successful remediators make it a company-wide commitment, requiring the wholehearted engagement of top management, the allocation of necessary organizational resources, and cross-functional collaboration focused on finding and eliminating the root causes.

A remediation program requires significant resources. Without intervention from the top, managers are stuck with the untenable burden of carrying out remediation activities and simultaneously completing day-to-day tasks. So companies should identify the necessary resources from the earliest stages of any remediation program. At a minimum, they should establish a strong project management office (PMO) tasked with coordinating remediation activities, tracking progress and measuring key performance metrics. For larger and more complex remediation efforts, it is prudent to set up an entire remediation organization led by a senior executive with sufficient technical and management resources on hand — including targeted infusions of staff from other divisions or from external contractors, when needed.

The hard work of remediation starts with a structured approach to root-cause problem solving — not simply by jumping on first- or second-order diagnoses. Ideally, the problem solving should be cross-functional. In one company, the sessions included personnel not only from the engineering, manufacturing and quality groups, but also from HR. That inclusive approach helped to pinpoint the fact that some production workers were not following established operating procedures.

Cross-functional collaboration is just as important once the root causes are clear. Quality and manufacturing must align on solutions and adjust their operating priorities consistent with the remediation program. Procurement and other functions might need to get involved, too. IT may need to step in to build systems that can capture more data or better analyze trends. And it may even be valuable for the R&D group to join in, postponing unrelated work in order to focus on solutions that change the product lineup, for instance.

2. Make Performance Management Transparent

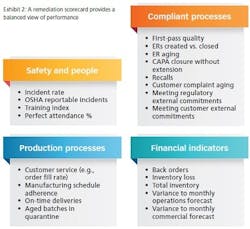

The work of remediation differs so much from that of the core business that it requires a very different approach to managing performance. The most successful companies establish balanced scorecards to track remediation activities and overall company metrics; they also create a robust forum to properly review this performance, and they aggressively manage the performance of third parties such as remediation consultants brought in to provide interim controls.

The best remediators also make a point of aggressively managing the performance of third parties. In one scenario, a large company set up a remediation control tower at one location to manage a cross-continental program involving nearly 1,000 contractors. The project managers had the tough job of remotely managing remediation initiatives and contractor activities across as many as 20 sites. The control tower provided transparency to all the PMOs so that the managers could easily track progress and performance. Control tower staff were able to rapidly escalate site-level concerns to project owners for resolution. Furthermore, the control tower facilitated regular communications and flagged key challenges on remediation progress to senior executives.

3. Ensure That Other Business Choices Support Remediation

Done properly, remediation can require not just extensive resources and management attention but also R&D and production capacity. To free up those elements without impairing the drivers of corporate revenue, companies have to be disciplined about setting priorities for a host of other activities. Cross-functional collaboration is essential here, too — with help from the strategy staff to make sure that the inevitable changes are consistent with corporate goals.

We’re pleased to report that we’ve seen many companies come together with business choices that are truly supportive of the remediation efforts. We’ve observed project managers working closely with the commercial function to simplify product lines, and manufacturing teams drawing on wider networks to shift production to other locations (either the affected product itself or close replacements for it) and expediting production to build up inventory before shutting down a production line. We’ve also seen some companies shifting important resources and talent from across the globe to support the location where remediation is needed most. That’s a meaningful sacrifice not just for the sourcing locations, but also for the individuals who must uproot and live away from home in order to support the remediation activities.

At one company, product managers quickly rationalized several SKUs. By shutting down production of a number of high-risk legacy products, they not only freed up resources, but also reduced demand for remediation work. Additionally, these managers delayed some marketing plans in order to free up space in plants. They could do this only because they were fully aware of the trade-off in value, and they used their business judgment to distinguish between the short-term gains available to them and the long-term success of the organization.

4. Communicate with the Outside World in disciplined ways

Remediation requires communication — and plenty of it. It is not something that can be dealt with by hunkering down and improving internal operations while ignoring the outside world. Pharmacos that try to “keep a lid” on remediation activities can soon find themselves embroiled in public relations crises. Open up any major news service after a big quality issue in the industry and you will find piercing headlines that grab the attention of the affected pharmaco’s customers and investors. The concerns ripple outward: Consumers will question the safety of the affected brands, while distributors and retailers will fret about the company’s reliability.

So a vital component of every remediation effort must be the ability to work well with external parties and communicate with them clearly, crisply, continually and proactively. Having a clear communication strategy is essential in working with regulators, shareholders, the media (including social media) and, of course, customers facing drug shortages.

In fact, we contend that it is absolutely crucial to establish a productive dialogue with regulators. Agency officials should receive continual updates on remediation plans and progress against those plans. Pharmacos must resist the temptation to merely send reports; instead, they should engage in a two-way conversation on how best to emerge from the crisis. At one pharmaco, the chief executive made it a top priority to personally communicate with the company’s regulatory agencies. In addition to the company’s delivery of concise quarterly reports on progress and challenges, the CEO scheduled multiple meetings to keep the regulators entirely up to date with the remediation effort.

Shareholders are the other constituency that must be kept in the loop. Communication with them should include not just the immediate operational challenge for which remediation is necessary, but also a vision of how the remediation investment will help the company become stronger, operationally and financially. Companies that have successfully navigated remediation have been upfront with shareholders about the required investment. They’ve also provided clear road maps on how costs will stabilize and what the post-remediation organization will look like.

5. Interim Controls

Remediation is a sign that the company’s existing quality controls have failed and must be rethought. Until new procedures are in place, regulatory agencies often require pharmacos to install temporary controls that provide greater margins of safety. These “interim controls” ensure sufficient oversight over quality in the company’s ongoing operations.

In addition to the added oversight, such controls signal how seriously the company’s leaders are viewing the remediation activities. In effect, the measures are saying, to both internal and external constituencies, “We know there’s an issue and although we don’t fully understand it yet, we’re acting immediately to protect patient safety and our overall reputation.”

In some cases, a company can administer the interim controls itself, but more often it will hire third-party consultants experienced in collaborating with regulators on these measures. Regardless, it is vital to clearly define the role and scope of the controls so that employees are more likely to break out of their usual work habits when problems arise. They might need to escalate quality issues to senior quality leaders much faster than they usually might or ensure double inspection for documentation. Controls should include metrics so that staff can be confident of which steps to follow during this unusual period.

However, interim controls should be just that: stop-gap measures. They should specify the time line over which a company can phase them out. Otherwise, companies can find themselves saddled with ongoing costs and burdensome procedures that become entrenched in the quality system.

On top of covering all of these functional needs, companies will also want to design the controls to generate knowledge about underlying issues in quality and compliance. This might require additional people or resources, of course. But the intensive oversight that comes with such controls can yield valuable information that would never surface in the course of normal quality practices — and at just the time when the organization is establishing a new quality system.

6. Practice Lean Processes

The actions taken after a quality and compliance incident are not expected to be highly efficient. The priority is to react fast and implement interim controls as quickly as possible amid considerable uncertainty. Remediation brings unfamiliar requirements that can easily slow down employees and production lines by creating new bottlenecks. Approvals that were dealt with quickly in the past may now require multiple new handoffs as well as sign-off from senior managers.

So it might seem counterintuitive to say that remediation is an ideal time to think and act “lean.” The focus should be on implementing requirements in efficient ways and ensuring that additional controls are adding quality to the process.

In one instance, a pharmaco assessed the performance of a remediation group assigned to investigate a quality problem. The company found that less than a third of the work actually was productive — in that it identified and eliminated the root cause of the problem. Other activities were wasteful, including a slew of auxiliary paperwork and excessive time spent fact-finding. With an understanding of the drain on time, the company took immediate action to add extra administrative support. Now, the group could focus on the main work: streamlining approvals and standardizing data collection processes.

7. A Culture of Quality

Remediation is a shock to an organization, and some employees will see it only as a time-consuming ordeal that they must tolerate. Employees are eager to move on as soon as possible and “check the necessary boxes” so that they can get back to operations as usual. Yet remediation can also be a golden opportunity to alter the way that the organization approaches day-to-day quality issues. Leaders can take advantage of the experience to instill a renewed quality mindset, to ensure that the company doesn’t find itself in another quality crisis a few years later.

Transforming quality can start with a “quality maturity” assessment that establishes a baseline for the current-state culture, highlighting the current quality mindset and the management and process gaps. Once the gaps are understood, specific interventions, initiated by employees and supported by leadership, can begin to change the quality culture.

The good news is that there are already many successful remediation stories out there. By incorporating these seven key principles into their remediation programs, and with the sincere support of leadership teams, companies that are launching remediation initiatives can be more confident that they can regain their footing — without any noticeable negative impact on everyday business activities.

The experiences of one large pharmaco show what’s needed to handle remediation relatively well:

Thorough assessment of the problem.

It wasn’t enough for the company to issue general calls to take remediation seriously. It was able to shift its culture toward embracing quality only by increasing organizational accountability . As one manager proudly stated, “We have created a system where people can’t find loopholes [so they] have to do the right thing.”

Managers were able to take immediate steps, such as taking difficult-to-manufacture products off the market for either remediation or elimination. The organization also benchmarked against external best practices to dig deeply into quality issues. “Answering 483s only touches the surface,” recalled a manager. “Without structured problem solving, we would never have gotten to the root cause.”

However, some elements of the remediation program were not handled in the most effective ways. The new quality system was not simple to use. There were persistent skill gaps affecting operation of the system, and the company suffered from a shortage of subject matter experts.

Organizational commitment.

The company wisely assigned a new leadership team to remediation — a team whose members were comfortable with critiquing the status quo. As one manager said, “It’s hard to get the architect of a system to change it; you have to place people in charge of the transformation who don’t have strong ties to the system in place.”

The new team worked to address key issues in a timely and efficient manner, with clear decision rights within the steering committee. The team members also demonstrated the willingness to make tough decisions, while fostering an open culture that made people comfortable with raising difficult issues. “We truly shut down R&D and focused all of our resources toward the initiative,” noted one member. “This sent a positive message about how serious we were.” And throughout, they kept the teams under them focused on solving the quality problem, without being sidetracked by related issues.

Nevertheless, some elements of effective governance did fall short. Decision rights weren’t so clear below the level of the steering committee, and individual remediation projects weren’t integrated enough. The remediation teams also had limited two-way learning with quality experts from other divisions. And leadership was fragmented at the various sites that were affected by the remediation initiative.

Communication.

The company did significantly better at communicating compared with its earlier compliance programs. It had a disciplined and targeted external communications strategy. Customers got important updates, but the company held back from providing guarantees. Regulators, however, got special attention. As one manager said, “Taking the lawyers off the front line was critical to building our relationships with the FDA.”

Internally, the company pressed forward with more open communication. Management appointed guides to speak about the program, and sessions for specific employee groups helped to pass along further detail. As the remediation projects unfolded, though, communication became more of a challenge. The program management office initially treated messaging as a secondary staff duty; the office had no communication professionals. “House message boards” drew a mixed response. Here again, the accelerated schedule left little time to prepare for change management in advance.