Drug development programs are no exception to the rising importance of quality for pharmacos. Increasing demands by regulators and business partners have made it imperative for quality functions to have scientifically sound processes for review and assurance, rather than solely fulfilling the requirements set out in regulatory guidelines. Regulators have increased enforcement of compliance, especially for vendors and other third parties and for trials conducted outside the European Union and U.S. used for EMA or FDA registration. Indeed, the number of warning letters relating to GCP and GLP has more than doubled in the past five years. At the same time demand is increasing for an evidence-based approach to development activities. This means pharmacos must focus on establishing and verifying a clear, measureable, and objective quality standard and account for the risk-benefit tradeoffs of a particular product or treatment.

A robust approach to quality in development programs is also required to proactively address and minimize vulnerabilities (such as those relating to clinical sites’ compliance and protocol integrity) that could lead to unexpected delays or regulatory interventions.

Pharmacos seeking to improve quality in development programs will find there is no “quick fix.” First and foremost, they will need to raise the organization’s awareness of quality’s importance in development and its potential impact on the successful commercialization and launch of products. They should ensure that the development function regards quality as a core capability and that the quality function proactively addresses issues and aligns its strategy with the development strategy.

Beyond raising awareness of quality’s importance, pharmacos need to strengthen four pillars to build lasting excellence for quality in development: organizational structure; process ownership and improvement responsibilities; skills, capabilities and tools; and quality metrics.

Achieving excellence in four pillars: What are the challenges/opportunities?

We have observed a common set of challenges and opportunities for each of the four pillars of quality in development:

1. Organizational structure. Pharmacos need to address the challenge of optimizing the quality organization’s structure given the varied activities that comprise the development value chain. Activities and oversight are fragmented not only among different parts of the R&D value chain (for example, pre-clinical, clinical and technical development), but also within the same step of the value chain (such as activities related to clinical trials from phase I to phase IV). Quality often has limited oversight of critical areas, such as the commercial function (including registries and education material) and vendors. Further complicating oversight, the quality function’s support services are typically fragmented across different units, such as regulatory QA and quality systems and training. Quality performance is also undermined by the absence of adequate interfaces between the quality function and various parts of the development value chain, including pre-clinical and clinical

development, pharmacovigilance (PV), technical development and national affiliates.

2. Process ownership and improvement responsibilities. In many cases, it is unclear whether the development function or the quality function is responsible for ensuring that a process is implemented and appropriately simplified. This can lead to the existence of several independent quality systems, each with its own set of standard operating procedures (SOPs) that are not well harmonized (for example, clinical SOPs, preclinical SOPs, and technical development SOPs). Multiple SOPs, each

entailing a number of process steps and roles, increase the complexity of quality assurance and often are not adequately supported by IT systems that facilitate access, use and efficient updating. The existence of multiple quality systems also means that quality support may not be scalable at the right stages of the development process, such as clinical, PV or business development and licensing.

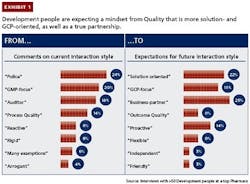

3. Skills, capabilities and tools. Many quality functions lack the skills, capabilities and tools to engage effectively and efficiently with the development side and influence its decisions. For example, the interaction style of personnel in the quality function is often not well aligned with development personnel’s expectations (see Exhibit 1). Development personnel perceive quality personnel as acting like policemen or auditors and having a manufacturing mindset focused on GMPs, whereas they are

looking for solutions-oriented business partners with a clinical mindset focused on GCPs. Among all development personnel, pharmacos need to raise the appreciation of and adherence to evidence-based decision making.

4. Quality metrics. In many development programs, key quality indicators (KQIs) are not effective for driving better quality performance. These metrics often are not harmonized with GLP or other standards. Many organizations fail to link their KQIs to clear consequences if targets are not met or do not provide incentives to promote continuous improvement.

Achieving excellence in four pillars:

How to make it happen

Leading pharmacos apply a set of best practices to capture the opportunities relating to each of the four pillars of quality in development:

1. Set up a “fit-for-purpose” quality organization. Top pharmacos ensure that the structure of their quality organization is well suited to supporting development programs’ business objectives. A fit-for-purpose organization has a clear structure that optimizes support for quality issues and drives higher internal efficiency in quality activities through better coordination.

Leading companies designate one clinical leader as the “single point of contact” (SPOC) to manage all quality-related activities in development. Integrated oversight serves to consolidate previously fragmented responsibilities and enables an end-to-end approach to quality that fosters consistency and alignment, internally and externally, among clinical activities that range from safety to technical development.

Leading companies also create specific groups to manage vendors and commercial standards. This helps them guarantee sufficient oversight and avoid fragmentation by integrating support functions such as Quality systems and standards and training into a single group. Moreover, they build a “continuous learning unit” through dedicated roles that allow a better alignment with training and continual improvement of processes.

Several pharmacos have rebalanced the staffing of their quality functions among locations. To be closer to recently relocated development organizations and gain cost advantages, they are relocating quality and compliance activities (especially standard or repetitive ones) to low-cost countries.

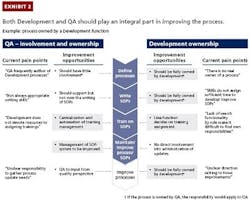

2. Strengthen the development function’s ownership of quality processes and improvements. Development organizations need to leverage the expertise of development process owners to design better quality processes, SOPs and support systems and facilitate their use. The outcome will be more efficient development operations and enhanced compliance through stronger adherence to processes.

Best-practice companies recognize this need and ensure that both development and quality leaders have strong ownership of quality processes and play an integral role in improving and simplifying them (see Exhibit 2). Business leaders identify the full list of processes and clarify process ownership and responsibilities between development function and quality. They can then take steps to simplify the processes. This includes ensuring that documents are not unnecessarily complex and making them easily accessible. For example, search functionality in the IT system used for document management can help individuals find their role in a specific process. Simplified processes also allow organizations to customize training for employees, who can focus on the specific steps and interfaces relevant to their jobs.

Simplifying processes also entails harmonizing quality and SOP systems with common quality procedures in GxP areas. This harmonization makes it easier for the quality function to continually optimize its efforts to proactively prevent quality issues from arising in clinical and non-clinical activities.

The example of a pharmaco that experienced numerous quality issues in clinical development illustrates the opportunities. Quality was not getting involved early enough in clinical trials, and the support it needed to provide was not clearly defined. Significant time was spent resolving issues that arose from ambiguities in the protocol and related documents. Development and quality personnel did not systematically track quality and compliance issues across all phases of the clinical trial process or systematically share information on quality risks across the clinical programs or teams. Moreover, the roles and responsibilities of the various quality functions were not always clear to the development personnel.

The company took several steps to address these shortcomings. It involved the quality function earlier in the process of developing the protocol and related documents, thereby reducing ambiguity and saving time and effort later in the process. The company designated a SPOC at the program level to proactively support the preparation of regulatory submissions. It facilitated the SPOC’s support by providing a set of checklists and detailed process steps to follow, including a QC checklist for protocol development and amendment process steps in critical submissions for QA to review CSR for quality issues. It also developed a handbook that details who is responsible for which activities within the organization and who to contact if an issue occurs. The company continually updates the handbook over time to prevent it from becoming obsolete. Finally, the company developed a database of lessons learned that provides insights from root cause analyses, which it shares with clinical teams

on a quarterly basis.

3.Develop mindsets, capabilities and tools that emphasize solutions and prevention. An emphasis on solutions and prevention helps a quality function identify potential issues before problems occur in development programs, thereby enabling faster and more efficient trial execution.

Rather than serving in a corrective, policing role, a quality function needs to be a partner to the development function in solving problems. When problems occur, it needs to support the development function in developing the right solution from a range of alternative solutions, as well as provide support in discussions with regulatory bodies.

Leading companies ensure that the quality function is proactively involved early on to shape the entire development process, such as by helping the function to develop and write clinical trial protocols. Best-practice quality functions also stay current on R&D trends in quality assurance and share this information with Development and other functions. This requires being in contact with regulatory bodies to understand topics that will be emphasized in oversight and regulation.

Leading companies also foster a true collaboration between quality functions and their development counterparts. They establish a clear governance structure, in which, for example, quality leaders are invited to participate in the development committee’s investment decisions. Quality leaders also have experience and expertise that allow them to engage in a “partnership of equals” with top managers in the Development areas.

Moreover, best-practice quality functions apply a clinical mindset when they work within development programs, rather than bringing the same mindset quality specialists apply to manufacturing processes. Systems and structures (such as metrics, discussed below) need to be aligned to support the development of the right mindsets and capabilities. Also, tailored training programs for personnel in both the quality function and R&D are essential for strengthening capabilities.

4. Establish KQIs to drive performance management. Pharmacos need a performance management system supported by effective KQIs to enable full oversight and clearly coordinated activities between the development and the quality function in key risk areas, such as management of vendors and contract research organizations and commercial QA. Tracking metrics and analyzing trends (such as recurring deviations) also enables continuous improvement in quality.

At leading companies, each KQI the organization uses has a clear definition that is understood by personnel responsible for monitoring it. The definition specifies what the metric will track, how it will be calculated, which performance cell (for example, the development organization, quality function or vendor) it applies to, and how poor performance will harm quality. Top companies also differentiate their metrics and related reports by performance cell and at different levels depending

on the clinical stage. Rather than including KQIs for different functions in a single report, the organization provides each cell with a report that only covers the KQIs relevant to its performance.

The KQIs selected should comprehensively cover all development areas. There is a risk that some areas may receive only partial coverage, especially those that are not well aligned with the rest of the development organization (such as technical development in a clinical development organization).

Care should also be taken to limit KQIs to a manageable number that can be reported through a simple performance dashboard. KQIs should be structured so that there are no overlaps and each can cascade through the organization, with metrics for lower levels rolling up to contribute to primary, high-level metrics.

Quality is set to become a key factor in the long-term success of development programs. As both regulatory authorities and business partners require more evidence in support of new drug formulations, pharmacos will find that ensuring quality in development requires a much deeper level of engagement than confirming compliance or taking corrective actions. Leading companies have already taken steps to restructure their quality organizations to meet the new demands on development programs and elevate the roles of development function owners in defining quality processes. And they are supporting and enabling these efforts with the right mindsets, capabilities and metrics. The positive outcomes include:

1) Better support of quality for the business, enabled by a clear organizational setup.

2) Enhanced compliance resulting from stronger adherence with processes.

3) Faster and more efficient trial execution, achieved by identifying and avoiding possible issues early

on through more preventive involvement and stronger solution-oriented mindsets and capabilities.

4) Full oversight and continuous improvement enabled through effective tracking and trending.

Given the importance of development to a pharmaco’s overall corporate strategy, companies that excel in these dimensions will be building a major source of competitive advantage.