Drug development continues to change dramatically (see Data Use and Misuse, below). As a result, the amount of information that pharmaceutical companies generate and collect during drug development doubles every five years. Unfortunately, only 10% of this information is ever leveraged to improve overall competitiveness and compliance [1]. We decided to find out why, in a survey (Pharmaceutical Manufacturing, April 2005, p. 73) designed to assess the current state of information and knowledge management during pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical process development.The survey (see Demographics and Process Development Growth Trends, below) benchmarked each respondent against an ideal, in which business and information processes are characterized by:

- Visibility

- Traceability

- Accessibility

- Leveragability

- Structured Data

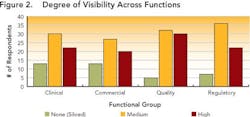

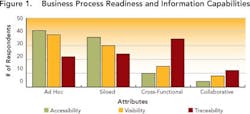

Data visibility and traceability appear to be limited in cross-functional processes involving multiple groups (e.g., manufacturing, quality, compliance). Figures 2 and 3 (below) summarize survey results.

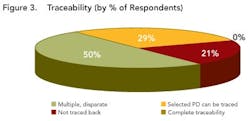

While a few respondents described no data visibility, most indicated that data were at least somewhat visible to various functional groups within their development organizations, indicating that their companies are at least taking the initial steps required to move beyond data silos.However, traceability is still limited, as shown in Figure 3 (below). While half of the respondents indicated that information could be traced, this was often done by paper searches and other labor-intensive activities, throughout the organization.

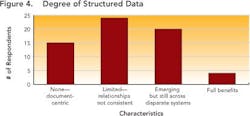

Close to 29% of the respondents could trace selected data back across the development lifecycle, but 21% of the respondents indicated that they could not trace data back at all and not a single respondent indicated that full and complete traceability could be achieved in their environments today.Outside four wallsClearly, poor data visibility, accessibility and traceability diminish efficiency and performance within any drug development organization. However, the negative impact only multiplies when this type of environment is replicated across an organization’s key alliances and partners.As pharmaceutical partnerships become increasingly important (see Demographics and Process Development Growth Trends, below), organizations won’t be able to sustain ad hoc data transfer. To prevent data from getting lost through the cracks, robust, mutually-agreed-upon data transfer systems are urgently required, supported by strong and flexible processes that will allow organizations to “do more with less.”The current FDA regulatory framework rewards companies that clearly understand their processes, whether for manufacturing or development. Clearly, if any drug development organization is to demonstrate full understanding of its development processes, it can no longer rely on disparate sets of spreadsheets, documents and siloed applications to analyze data.Establishing context around every piece of drug development data will be essential to ensuring process understanding and regulatory compliance. Each isolated piece of information will need to be correlated and linked with other pieces of information.For example, drug product lot data will need to be associated with production equipment and the state of that equipment (e.g., maintenance records). But the same lot data should also be associated with data on intermediates and raw materials, including vendor data and Certificate of Analysis (COA) information, as well as the process steps that were carried out, the analytical results and the operators who were on duty that day in that particular facility.The survey indicates that drug development organizations are still a long way from establishing data context. In fact, most companies continue to take a flat, document-centric approach, rather than the multi-dimensional views essential for successful drug development today.Some organizations are taking marginal steps to improve their development team members’ ability to use documents, for example, by offering keyword search capabilities. But fewer than 5% of respondent say that their organizations are taking advantage of structured databases (Figure 4), while 15% indicate that they have no structured data capabilities at all.

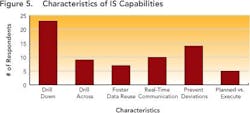

Nobody could clearly identify structured data benefits offered by their existing IT system (Figure 5, below). When asked about “drill down” and other capabilities, only 20% of the 90 people who responded to this question could name two or more characteristics, and only 5% could answer that they had four or more of the characteristics listed.These characteristics maintain the context under which information is generated, and correlate data across key development parameters (who, what, where, when, how) for the entire development lifecycle, allowing practical planning, execution and analysis to take place. While “drill down” capabilities take the user to the right frame of reference for the detailed search — whether by time, date, project or phase — “drill across” capabilities allow users to develop the relationships between processes, materials, equipment, environment, personnel and operating modes (e.g., GMP vs. non-GMP).

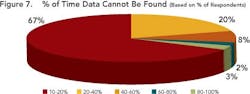

Enabling this context and maintaining the correlation allows development users to follow the thread of information as it is revised, ensuring that all changes are made for the right reasons and determining the impact that such changes could have on overall product performance. Maintaining correlation also ensures that the history and evolution of changes made in a process route or a material can be captured and accessible throughout the development life cycle. Together, these capabilities allow users to pull up and understand data that may have been generated several years ago, ensuring that yesterday’s lessons are applied to later-stage commercialization studies such as comparability studies and campaign summaries.Responses (Figure 5, above) show that many companies don’t have the right infrastructures in place to realize the full benefits of structured data. This lack may prevent them from achieving the goals outlined by FDA’s Critical Path and PAT initiatives, both of which aim to foster a culture of doing things “right the first time” and being more predictive by leveraging lessons from the past.Only a few respondents (between 7 and 20 out of 104) have systems in place to help users avoid mistakes, proactively — for example, notifications that can help an operator make necessary adjustments before the issue becomes an irreversible problem or becomes a reportable error.Size doesn’t matter!Interestingly, both ad hoc and data silo practices occurred in companies regardless of size. Relying on unstructured data and having limited proactive decision-making capabilities appears not only to prolong the time required to search for data, but leads to unnecessary duplication of efforts — for example, repetition of experiments. Figures 6 and 7, below, indicate the average time that individual researchers or development professionals spend looking for data, along with the percentage of time that data cannot be located at all. On average, respondents spend almost five hours per week (or nearly 13% of their time) looking for data for reports that they must prepare, whether progress reviews, filings, technical summaries or engineering studies.

Two-thirds of the participants could not find the information they needed approximately 10% of the time. A combined 28% of respondents indicated that data could not be found between 20% and 60% of the time.

This inability to find important data puts any organization at enormous regulatory risk and drains the scientific and engineering lifeblood of drug development. But it also reduces pilot plant capacity utilization, and increases the cost of running lots and batches due to the number of experiment “reworks” or repeats that have to be executed to fill various information gaps that may exist.Figure 8, below, shows how it leads to unnecessary “rework”, even during late-stage process characterization and commercialization. 63% of the participants said they had to repeat experiments at least 10% of the time and 31% reported having to duplicate efforts 25% of the time. Overall, 8% of the experiments or tests must be repeated when data cannot be located, a significant direct cost, but an even greater opportunity cost, particularly for pilot plants that are running near capacity.

To help make these costs more tangible, we looked at the results of a 2001 survey of 21 pharmaceutical companies. One of the outputs of the survey estimated that 25% of drug development costs were associated with the Cost of Goods Sold with 12% attributed to R&D expenditures. [2] Applying just a 25% reduction in the number of repeat experiments could cause a significant shift in the cost breakdown. Indeed, reducing the number of experiments repeated by just 25% and moving the costs out of COGS to the 12% R&D spending, could increase the R&D budget by as much as 50%!IT systems and user satisfactionThe survey also examined how satisfied participants are by their existing IT systems, particularly given the growing trend of repurposing existing commercial systems for the drug development function. Participants were asked to rate their current systems’ ability to capture information, assessing their ability to:

- Capture large amounts of data created from different sources and types throughout development;

- Enable traceability across the full/complete development life cycle and capture composite views at specific points in time critical to build process understanding or assess status;

- Identify and organize operating discontinuities typical within product development — for example, stop/start nature of campaigns, stop/restart development activities on a compound, changes in clinical or commercialization dates, or development priorities

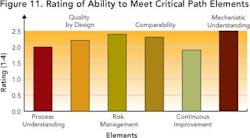

Results indicate that companies are far from achieving the “desired state” required to manage information, and indicate improvement opportunities.Staying on the Critical PathAre today’s drug development organizations ready, from an IT perspective, to reach the “desired state” of drug development? Survey responses (Figure 11), and an average rating of 2.2, indicate lack of alignment between existing IT systems and future goals.

Despite the obstacles and challenges they face, development professionals have a clear “wish list,” summarized below:

To achieve the operational efficiencies afforded by better information management and integration across the process development enterprise, companies must move towards a system that captures data in a systematic, structured and actionable fashion and eliminates information gaps allowing them to leverage data to make decisions and establish rationale.The goal is converting information into knowledge — actionable data that will enable full traceability along the complete set of dimensions making up drug development.References

Ken Morris, Ph.D. – Professor and Associate Head of Industrial and Physical Pharmacy at Purdue University, Dr. Morris joined the faculty in 1997, after working for Squibb and Bristol-Myers and teaching at Rutgers and St. Johns. He is also the technical director of Purdue University’s CAMP (Consortium for the Advanced Manufacturing of Pharmaceuticals), the outgoing associate director of the Center for Pharmaceutical Processing Research, and one of the founders of the Particle Technology and Crystallization Consortium. Dr. Morris received his Ph.D. from the University of Arizona in 1987.Sam Venugopal – Director of Conformia Software’s Life Science Operations, he has over 15 years of management consulting, market research, and technical experience with companies that include Pittiglio Rabin Todd & McGrath (PRTM). At Conformia, Mr. Venugopal currently co-investigator on a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) with FDA, which is examining the root causes of drug development bottlenecks.Michael Eckstut – Vice President of Conformia Software’s Life Science Operations, he has specialized in pharmaceuticals and life sciences consulting at companies that include A.T. Kearney. Mr. Eckstut serves on Booz Allen’s Board of Directors and is co-chair of the Keiretsu Forum’s life sciences committee.

| Area |

Description |

| Business |

|

| Science |

|

| Compliance |

|

- AMR Research Report, Enterprise LIMS Market Research Study, 2002.

- Raju, G.K., Components of Pharmaceutical Industry Costs, a presentation made in 2001.

Ken Morris, Ph.D. – Professor and Associate Head of Industrial and Physical Pharmacy at Purdue University, Dr. Morris joined the faculty in 1997, after working for Squibb and Bristol-Myers and teaching at Rutgers and St. Johns. He is also the technical director of Purdue University’s CAMP (Consortium for the Advanced Manufacturing of Pharmaceuticals), the outgoing associate director of the Center for Pharmaceutical Processing Research, and one of the founders of the Particle Technology and Crystallization Consortium. Dr. Morris received his Ph.D. from the University of Arizona in 1987.Sam Venugopal – Director of Conformia Software’s Life Science Operations, he has over 15 years of management consulting, market research, and technical experience with companies that include Pittiglio Rabin Todd & McGrath (PRTM). At Conformia, Mr. Venugopal currently co-investigator on a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) with FDA, which is examining the root causes of drug development bottlenecks.Michael Eckstut – Vice President of Conformia Software’s Life Science Operations, he has specialized in pharmaceuticals and life sciences consulting at companies that include A.T. Kearney. Mr. Eckstut serves on Booz Allen’s Board of Directors and is co-chair of the Keiretsu Forum’s life sciences committee.

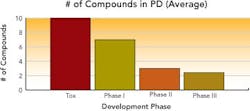

Respondents had on average 18 total compounds in development, with approximately three compounds each in Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials, and roughly 15 in early-stage development. Several manufacturers had as many as 40 to 50 compounds in development.

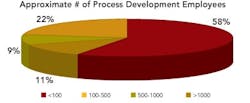

More than half of the organizations had less than 100 staff in development, with 11% having more than 1,000. Of the 35% of respondents representing international, multi-site development operations, 40% indicated that their companies employ over 500 people in drug development.

Collaborative partnerships have helped many respondent companies grow their process development efforts. These partnerships are used to access compounds at different stages of development, access technologies for synthesis or recovery and obtain capacity at a reasonable cost. Between 40% and 50% of the respondents said that they will increase partnerships across all phases of development over the next two years.

About the Author

Ken Morris

Ph.D.

Sign up for our eNewsletters

Get the latest news and updates