Implementing a single control platform across all plant-floor applications provides you with a number of advantages, including reduced spare-parts requirements, more synchronized processes and lower maintenance and training costs. It also improves plantwide integration by enabling the seamless transfer of real-time data from disparate control systems for improved decision-making and increased manufacturing flexibility.

Many plants with process applications have an outdated distributed control system (DCS). As these systems reach the end of their useful life, migration to a new automation system is required. However, before this can take place, you must provide financial justification.

This justification must compare the cost of continued DCS operation to the costs and benefits of migration to a new automation system — or the total cost of ownership (TCO) for each system. This is the most comprehensive way to analyze and justify a DCS migration project. TCO takes into account all relevant financial factors, including purchase price, maintenance costs, energy consumed, downtime and quality.

Evaluating the Old System

Excessive maintenance and support costs, along with high levels of downtime, are the most visible reasons to migrate from a DCS to a new automation system. They’re also the easiest to quantify. Older DCSs can become expensive to operate and maintain for three reasons:

- Increased system failure due to deteriorating components.

- Difficulty procuring spare parts.

- Lack of qualified maintenance staff.

All three of these, in addition to product changeovers, can cause excessive downtime and increased costs. This is a significant expense for continuous process operations because plants typically take hours or even days to restart after an interruption.

Harder to analyze are the costs associated with poor process control. Substandard process control results in excessive energy use, poor quality and reduced throughput. Controlling the process tighter to set points helps maximize these components and minimize waste.

For example, heating a product to 0.1° over its set point consumes less energy than heating it to 2° over its set point. For plants running batch processes, adding too much of an ingredient can create an unacceptable product, and thus scrap. Even if the batch is acceptable, costs might be higher than needed if the ingredient is added in excess quantity.

It’s also important to consider the system’s level of integration with third-party hardware and software platforms. Older DCSs generally don’t support modern, open communication standards, so it might not be possible to add needed features. With a new automation system, additional features can be built in or relatively simple to integrate.

New Automation System Costs

In addition to calculating the TCO, you also need to quantify new automation system costs and benefits. New system costs can be broken down into three main categories:

- Installed cost of the new automation system.

- Cost to train employees on the new system.

- Downtime incurred while installing the new system.

The first two costs are generally straightforward to quantify because suppliers can give fixed-price quotes for each.

The cost of downtime incurred while installing the new system is harder to quantify, but can be minimized by following a three-phase migration method. Breaking up the total required downtime into multiple periods often is advantageous and spreads migration costs out over a longer period.

In phase one, the most obsolete components — the human-machine interfaces (HMIs) — are converted first. This often can be performed with minimal downtime, and in some cases, none.

In phase two, the legacy process controllers are replaced while allowing processors to reuse existing I/O modules to maximize the return on their existing investment.

In phase three, the I/O is replaced. In many cases, automation suppliers have wiring solutions that allow you to remove legacy I/O without the need to remove field wires, reducing installation costs and risks associated with I/O replacement.

Financial Analysis

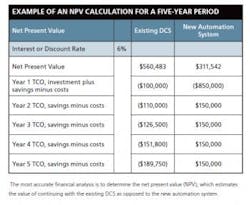

The final step in justifying the value of migration is a financial analysis. The most accurate financial metric is the net present value (NPV). The NPV estimates the value of continuing with the existing DCS as opposed to the new automation system. It also incorporates the interest rate, referred to as the corporate discount rate.

The NPV can be difficult to quantify because it requires annual costs and savings for each option to be listed for the expected life of the shorter-lived option. For example, if the DCS will be obsolete and unsupportable in five years, then the annual TCO for the existing DCS and the new automation system would have to be calculated for each of the five years, with all values discounted back to the present. The table below shows an example of an NPV calculation for a five-year period.

As the table shows, the existing DCS has an annual TCO of $100,000 that’s increasing at a rate of 10% the first year, rising by 5% per year to 25% in the fifth and final year as the DCS becomes increasingly unsupportable. In the end, a new automation system would require an investment of $1,000,000, but would save $150,000 per year in TCO as compared to the existing DCS.

Do It Right

Comparing the TCO for the existing DCS to that of a new automation system indicates whether the migration is financially justifiable. Outside assistance sometimes is required to evaluate a prospective upgrade, and this can be provided by consultants, system integrators or automation suppliers. A good partner should be able to provide much of the data required, help you identify your needs and put together a migration plan based on your goals, constraints and future plans.

Rockwell Automation

Migration Solutions

Published in the May 2013 issue of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

About the Author

Mike Vernak

Rockwell Automation

Sign up for our eNewsletters

Get the latest news and updates