The Shingo Prize has been referred to as the Nobel Prize in manufacturing, but you won’t see much glitz or glamour at its annual ceremony in Florida. Like its namesake, Shigeo Shingo, the Toyota engineer who brought so many Japanese phrases into the U.S. manufacturing lexicon, this prize focuses on the nitty-gritty shop-floor issues, the details that are still taken far more seriously by the average aerospace or automotive manufacturer than the typical drug maker. Examples include “visual” and mistake-proofing systems, often simple devices that improve efficiency and reduce waste, and help keep operators focused on areas for improvement.

One does not “win,” but receives this prize, emphasizes Ross Robson, a self-described “pracademic,” who has directed the Shingo Prize for 18 of the 19 years that it has been in existence. Most Shingo recipients have been aerospace and automotive companies.

Baxter’s North Cove 2,100-person manufacturing facility in Marion, N.C. (a 2005 Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Team of the Year) became the first drug manufacturer to win this award seven years ago, and this year became the first-ever “two time recipient,” Robson says. But Baxter’s 1,000-person Cuernavaca facility in Jiutepec Morelos, 45 miles south of Mexico City, also received a Shingo this year, the first Mexican drug manufacturing plant to be thus honored.

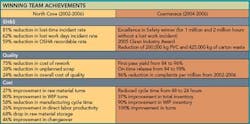

Both facilities are noteworthy for product flow, and Cuernavaca showed major continuous improvement in just a few months, Robson says. “Employees at both facilities clearly have a sound understanding of Lean principles, tools and culture, and North Cove has raised the bar considerably since it won its first award,” he says. The results that these teams have achieved so far speak for themselves.

Applying for the prize is not for the lazy or unfocused. Applicants must complete a 100-page, four-section achievement report, a process that took a team of 10 people at North Cove some 18 months to complete, says manufacturing director Beverly Smith. “It takes three months just to gather all the data,” says Ivonne Nogueira Flores, who led the Cuernavaca team’s improvement efforts.

Click chart for larger image.

However, even preparing the submission is a learning experience and provides focus, says Baxter North Cove plant manager Tony Johnson, who has become one of the company’s operational excellence gurus and a “go to” guy for questions about Lean and Six Sigma implementations.

Judges check what’s in the report against Prize criteria. Applicants are graded, with 1,000 points being a perfect score and 765 the cutoff point. “We look for inconsistencies across various categories, or holes in thinking, where actions we see within the plant don’t appear to match up with what they’re saying in the report,” explains Prize examiner (and 2006 winner) Gwendolyn Galsworth.

Often, reports are very uneven, Galsworth says, showing that the facility may excel in one area, but is weak in another. It’s also important that the report reflects reality. Companies that hire a consultant to write the report miss out on an extremely valuable learning experience, she says. “Have a consultant review your report, but get the people involved — who are doing the work — to write it.”

Those 15 facilities whose applications have the highest scores must then agree to a one-and-a-half-day site audit conducted by a team of five or six experts from the Shingo Prize Board of Examiners in Lean, Six Sigma and Op Ex from various industries. After a presentation by the project leader at the host facility, reviewers split up for plant audits, each covering a different area, to “verify, clarify and amplify” what’s in the written report.

The auditing team then usually meets briefly to decide what to pursue and whether “deep data dives” are needed into financials, HR and turnover, delivery or on-time schedules, Galsworth says. After a few hours, the auditors submit a list of documents they want to examine. Security is ensured because all reviewers sign strict nondisclosure agreements, but they must be given full access to any nonproprietary documents they request.

Then the actual assessment begins, based on what the team sees at the site.

One critical yet often overlooked ingredient for a successful plant audit is the presence of effective visual devices on the plant floor — boards and other tools that convey to employees the information that’s needed, when and where they need it. “This may not show up all that prominently in the report application, but it is very important in scoring the facility,” Galsworth says.

Politics are kept out of the judging process, and prize recipients are selected by consensus. The team leader, Galsworth says, is critical in discussing “outlier” results, starting open discussion and ensuring that nobody just gives up and says, “Okay, I have to catch a plane.”

Baxter’s Cuernavaca team members in action. Since the team members couldn’t all go to the award program, special celebrations were held at the Cuernavaca and North Cove facilities.

Writing the site report, which is later sent to the host company, then takes another portion of a day, but examiners too learn a great deal. “Different experts bring different complementary strengths,” says Galsworth.

North Cove:

Refinement, Critical Mass

For Baxter North Cove, there had been no significant changes in direction or new points of emphasis within its existing continuous improvement program. Instead, the facility’s staff has been refining existing practices. “More team members have been through the training, so our critical mass is larger than it was seven years ago,” says plant manager Johnson. In addition, more operations, beyond manufacturing, have been integrated into the value stream.

The facility has staged Kaizen events with its suppliers, both internal and external to the Baxter corporate network. One of these sessions led to a change in the type of container used, from disposable to reusable, explains manufacturing director Smith.

Within the past two years, the facility’s teams have been focused on digitizing information, Johnson says, making necessary data available, from the most recent report on employees’ vacation time and attendance to manufacturing and business KPIs.

It’s important, Johnson advises, not to get hung up on the “prettiness” of the data display, because that tends to be directly proportional to the amount of care and feeding the system requires. “We didn’t want ‘monsters’ that we’d have to feed, so we selected systems where data were easily accessible but that wouldn’t take a lot of time to update,” he says. The facility measures OEE across every production line, using both manual and electronic methods, he says.

Baxter Cuernavaca started its Lean program in 2004, driven by the company’s overall quality leadership program. There are 800 manufacturing employees, but over 1,000 when distribution and other functions are included.

Visual Stream Mapping Is Crucial

Visual stream mapping (VSM) was the single most powerful tool that the facility used, says plant manager Alejandro Ochoa, to identify the key types of waste: overproduction, movement, inventory, rework and defects.

VSM directed all other efforts, from waste identification to plant layout changes and team assignments. “In the past, when looking at employee productivity, we were thinking of efficiencies but we didn’t see the whole process and such things as inventory levels,” Ochoa says.

Basic training was an important first step, says project leader Ivonne Nogueira-Flores. “We provided specific training, based on area requirements, whether Lean, Six Sigma, Kaizen, SMED (Single Minute Exchange of Die), Just in Time (Kanban) or Error-Proofing (Poka Yoke).” A number of different approaches and formats were used, she adds. In some cases, consultants helped set up a program; professors from local universities also assisted.

One of the most powerful training tools the facility has is a simple tour, Nogueira-Flores says. Conducted monthly or bimonthly, these tours invite people from different functional areas to see “how the other half lives.” For example, a packaging line professional will visit the quality lab or the manufacturing floor.

Poka Yoke and Visual Taken Seriously

Baxter Cuernavaca is taking mistake-proofing very seriously, and has a specific program in place designed to improve it, with process engineers assigned to it, Ochoa says. Options range, Nogueira-Flores notes, from use of sophisticated software to control mixing, to placing a small device in a sampling line to prevent the wrong connection.

On a filling line, for instance, where it is imperative that the right anticoagulants and additives be added to the right bag, Baxter uses different port sizes, with a different diameter tubing for each, to avoid mistakes. “It’s simple but effective,” Nogueira-Flores says. In sterilization, the facility uses barcoding with a software package that controls the movement of 1,000 trucks, or containers where product is placed to be sterilized, per day.

“Poka Yoke is not rocket science,” says North Cove’s Johnson. At his facility, mailbox flags are placed on the containers in which empty bags are moved from one location in the plant to another, to show whether they’re full (flag up) or empty (flag down). This system has the advantage of both functioning as a “pull,” signaling the need to produce when they’re empty, and preventing errors (flag up vs. down).

Similarly, flags have been put on some of the machines to indicate the status of production. “It’s the proverbial square-peg-in-the-round-hole approach,” Johnson says.

Visuality of data is also critical. It’s the key to employee involvement, says Cuernavaca’s Nogueira-Flores. “Without this information, they cannot succeed,” she says. “We used to meet once a week for about an hour with 20 pages of documentation on every batch and its status, but a lot of those batches were still there the following week,” says Terry Foxx, who is, along with Smith, a manufacturing director at North Cove.

The company set up a board where every batch is visually moved, depending on how many days it has been sitting there. “[Now] we meet at 8 a.m. every morning for 15 minutes, and are kept up to date on everything,” he says.

Plant manager Johnson also meets with staff every morning to talk about what happened during the previous day in terms of output, machine downtime and the key metrics that each line records. It’s a standup meeting that takes 10-15 minutes out in the center of the plant. “Anyone can walk over and report, and update the team on quality, uptime and output,” says Johnson. The data are also posted — and kept updated — on all the hallways that operators must walk through, adds manufacturing director Smith.

Baxter uses 6S (with the last S standing for security) as a basic platform from which to establish the commitment and discipline that employees will need to follow the procedures required for other aspects of OpEx such as Kanban, she says. “It’s also an excellent tool for good manufacturing practices (GMP), mandated by FDA,” she adds.

VSM led to changes in plant layout to minimize wasted motion, Ochoa says. One such change halved the distance that employees must travel in the plant.

Wasted time between batch changeovers was also addressed using Shingo’s “Single Minute Exchange of Die” method. For one sterile plastic sheet operation, it used to take seven hours to change the rolls, Ochoa says. It now takes 25 minutes. Similarly, in another area of the plastics plant, changing from a 6-L to a 1-L filling machine reduced changeover time from four hours to 20 minutes.

Cross-Training

Formal training is important at Baxter, which advocates the “Lean Six Sigma” approach, Ochoa explains. The facility currently has 20 to 24 green belts certified by Mexico University, but only one or two black belts.

Cross-training has been an essential part of Cuernavaca’s program, Ochoa points out. “In the past, employees specialized just in filling or packaging, but with Kanban they must be able to move to different lines,” he says. “We believe that each and every employee should be able to work in three different positions in three different lines.” Depending on the complexity of the position, that training can last from three weeks to six months.

For both applicants and judges, the Shingo Prize offers an opportunity to benchmark manufacturing operations and gain insights from outside the drug industry. North Cove’s Johnson has judged teams, and describes it as a very educational opportunity. Even if you haven’t won the prize, experienced professionals can apply to join the Board. For more information, visit www.shingoprize.org.