This year, 139 professionals working in the pharmaceutical industry took our survey on Operational Excellence, with between 92 and 99 individuals responding to every question. Results indicate broad trends and signal some changes from previous survey results.

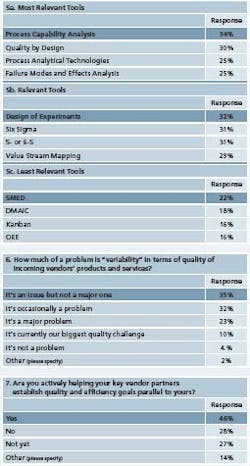

What united respondents this year were three overarching goals (Figure 1), in order of priority:

- Improving internal quality systems

- Increasing manufacturing agility

- Boosting capacity utilization

They were also unanimous in viewing management as the leading obstacle to continuous improvement, with 36% citing senior management and 34%, middle management (Figure 2). “Middle management wants to reap the benefits of what Lean and Six Sigma can do,” writes one respondent from a Big Pharma company, “but they do not want to take the time to educate the line operators on why we are doing what we are doing. So, with the operators, you have to get and keep them involved.” When asked about Quality by Design, less than 20% said the concept had full support from top management, where 52% said it had “some degree of support.”

Roughly 11% said top management paid lip service to QbD but didn’t actively support it, where 14% said it wasn’t even on management’s radar screen. (Figure 3) For Lean and Six Sigma, a quarter of respondents said these programs were fully supported, 36% said theyhad some support, but another 36% said they were either not really supported or not supported at all. (Figure 4) In verbatim comments, some respondents described changeresistant cultures within their organizations. “There’s a reluctance to investigate new areas and incorporate them into practice, even after they’ve been proven to be safe and effective,” writes one. Strained resources have only increased the level of fire-fighting at some facilities, where continuous improvement has fallen to the bottom of the priority list. “There’s not enough time, given the constant press of production,” explains one respondent. Others describe a situation in which Lean Six Sigma efforts are piecemeal and results fail to coalesce or last.

Complains one, who works at a mid-sized facility owned by a top pharmaceutical company “We are trying to implement Lean Six Sigma, but we only seem to ‘get started’ and never fully integrate the methodologies,” hewrites. “For example, we do 5-S but we don’t follow through to make sure we are keeping it up after each exercise. We talk about DMAIC but only during a Six Sigma project.”

In addition, for most respondents, concepts of Lean Six Sigma are only being applied to manufacturing, rather than throughout the organization. 41% of respondents said their organizations were applying the concepts to quality, R&D, and other operations. Experts on Lean and continuous improvement agree that regulatory pressures have made the adoption of Lean a bit slower in pharma than it has been in other industries. “The drug industry is not lean,” says Avi Edelstein, partner with the consulting firm, Tefen, Ltd. (New York City), “It’s not even close.”

Perhaps readers can take heart from the fact that peers from many industries, including some that have been at this for a long time, report suffering from the effects of “Lean as Mistakenly Executed,” the symptoms of which are:

- Lack of management support

- Failure to solicit suggestions from those actually performing the work. This is usually followed by failure to act on those suggestions, and then to offer tangible rewards to individuals for those ideas.

- Ongoing confusion of Lean programs with cost-cutting

- Isolated results.

Experts note that Lean and continuous quality take time to become established within any corporate, or industrial culture. Joseph Juran, whose Quality by Design book and concept helped transform Japanese and U.S. manufacturing, used to describe the situation with this homespun simile, relates Joseph De Feo, CEO of the Juran Institute (Southbury, Conn.). Quality, Juran said, is like an egg. If you try to rush its hatching by applying heat, the egg not only won’t hatch, it will become hard-boiled.

Avoiding the Tool Trap

“Many people fall into the tool trap, says Fred Greulich, director with Maxiom Group (Waltham, Mass.). “They learn and implement a few tools, post a few short term results and call it Lean or Six Sigma,” he says, noting that there are really three separate, yet integrated dimensions to a successful Lean implementation: an operating system, a management system, and a set of tenets and beliefs that underlies them. “You also need to implement a new set of metrics to support Lean or Six Sigma,” he says. “Success also requires that you have enlightened leadership that is asking the hard questions and rewarding the right behaviors.”

What is essential, Greulich says, is connecting Lean and Six Sigma to business objectives directly. A lot of pharmaceutical companies may understand that “process is king” as far as the actual steps involved in making a product — the SOPs, batch records — but the same mindset must be carried forward when it comes to managing and improving other parts of the business, including engineering and back office functions. Management support is critical, he says.

“You can’t call it Lean or Six Sigma when someone at a low level in the organization gets interested in 5S, Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) and other tools and applies them in a few places. They can try some things in good faith and score some early wins, but without leadership, they can’t migrate or sustain these initiatives,” he says. At the heart of the problem is failure to manage for quality and reward individuals for their contributions.

As Greulich explains, Lean change occurs at the micro process level, the level where real work gets done. “Many have no appreciation for the micro process level. They’re functioning at the mega process level and don’t know what’s going on down there. Enlightened leaders need to understand.” “Top pharma management is generally hands off,” says Tefen’s Edelstein.

His company, like many in the field, makes it a point to bring executives to the floor and pull them into the fabric by setting up a structure with regular meetings. “At too many facilities today, there are fires to put out and SOPs to sign, and until the top level readjusts its priorities and shows strong commitment to Lean and continuous quality improvement, programs won’t show the results that they could,” he says.

New Patterns, Inconsistencies in Survey Responses

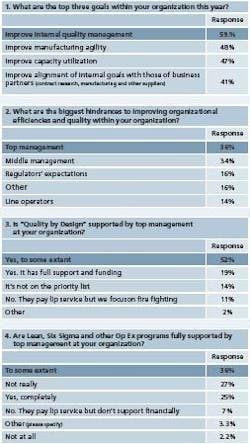

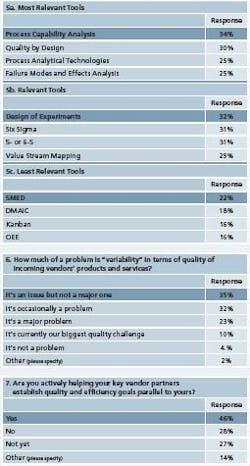

Most interesting in survey responses this year was a newfound respect for process capability analysis (Figure 5), which was cited as the most frequently used tool. In previous surveys, Cpk had been rated as less important. In addition, this year, more respondents noted that they were using process analytical technologies (PAT) and that their companies were adopting Quality by Design.

FMEA is also becoming more widely used, responses suggest. Howeverthere were some areas where goals and tools seemed to be out of synch. Respondents noted that improving internal quality management was Goal number 1, and the top tools they selected: QbD and process capability analysis were in line with that goal. Error proofing, being used at roughly 20% of respondents’ facilities, figured higher than it did in past surveys.

However, goals 2 and 3 were manufacturing agility and capacity utilization. A closely allied goal: reducing changeovers, was lowest on respondents’ priority lists. “Reduced changeovers was the second lowest goal of all, when in fact, that’s the best way to achieve manufacturing agility since changeovers can be one of the biggest time consumers in any manufacturing operation,” notes Edelstein.

In addition, he notes, the tools required for agility and improved capacity utilization — specifically, OEE and SMED — were not in the top list of methodologies. Edelstein also found it troubling that Six Sigma’s DMAIC process figured so high on some respondents’ lists of tools. “It’s nothing more than a structured methodology to run a program,” he says. “Unfortunately, in many organizations, it becomes a goal in and of itself, rather than a means to an end.”

He has seen that Six Sigma efforts at companies undergoing lean can get too methodical, to the point where efforts can become mechanical. For instance, some companies may decide they need to train 50 green belts in 16 weeks, only to struggle to find projects for them later. “Some of these green belts will be dealing with real improvements, while others will offer results only on paper,” Edelstein says. Respondents said that variability of product quality was less of a problem at their facilities (Figure 6).

However, it was still seen as a problem. “Variability of incoming components means that equipment setups are harder than they should be,” writes one. “We need to trend incoming vendor products to identify variability or shifts,” writes another. “As long as the product is in spec, QA approves and we’re not using statistical process control for trending, but we plan to start to use SPC for all incoming products and materials.”

With so many respondents focused on improving internal quality working to improve supplier quality systems was somewhat less of a priority. However, efforts are underway, and respondents say that they are developing programs with external suppliers (Figure 7). “We have trained some of our suppliers in Lean and Six Sigma and we have a support program but it is not widely used,” writes one. Several respondents noted that training and continuous education were becoming more important.

So, too, is knowledge management, and most respondents said that their organizations had procedures in place for sharing manufacturing knowledge to improve overall product development and QbD. Respondents all noted ambitious goals for this year, including: Improving overall speed throughout the value stream, empowering employees, improving safety and education, and reducing costs. Some noted specific goals: registering 12 more products with the national drug authority, one noted, or demonstrating the safety and efficacy of using vaccines as “immunodistractants” without carcinogenesis or the effects seen with traditional immunosupressants.

For another, the goals were streamlining new product introduction and tech transfer, establishing a continuous improvement culture and increasing process understanding capabilities and controls using value stream maps. Whatever your specific goals, experts agree that Lean and continuous improvement are important and well worth the time and effort they require. As the poet Rilke once wrote, “Nothing worthwhile is ever easy.”