President Obama’s first 100 days in office have already signaled a major change in the Administration’s stance toward FDA. Sympathetic observers say the Agency has struggled with unfunded mandates, rapid industry globalization and staff morale issues ever since former president Ronald Reagan trimmed the ranks of its reviewers and inspectors in the 1980s.

Although the nominee for FDA Commissioner, Margaret Hamburg, has yet to be approved, her deputy, Joshua Sharfstein, whose tenure has already begun, has long been critical of industry practices.

Sharfstein also spent time working as an aide to Rep. Henry Waxman, who has long accused FDA of “getting too cozy” with industry, and who analyzed and attacked its enforcement record last year (you’ll find the report here).

Senators Grassley (R, Iowa) and Kennedy (D, Mass.) have, once again, introduced a bill that aims to increase the power of FDA. Similar legislation they’d proposed last year never reached a final vote. This new bill would allow FDA to issue subpoenas and stop suspect imports at the border without approval of U.S. Customs. It would also put the onus on manufacturers to ensure that new drug applications are not misleading, and meet regulations. Failure to meet these regulations will trigger criminal and civil penalties.

In the meantime, HR 750, the FDA Globalization Act of 2009, proposed by Congressman Dingell, would increase funding for inspection of offshore manufacturing plants and, among other things, require disclosure of country of origin for all active and inactive ingredients used in any drug formulation.

Setting the new tone, even before the new President was elected, were key bills strengthening FDA’s enforcement powers, as well as the appointment of consumer advocate Sydney Wolfe to FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management. Now, observers note that the Agency seems more determined than ever to distance itself from the industry, and to step up enforcement.

Speaking even more eloquently to the change in climate is the $3.2-billion budget that FDA has requested for 2010, representing a 19% increase from last year. This figure includes budget increases of $295.2 million and an extra $215.4 million in industry user fees.

Drug companies that do not have a compliance strategy in place may soon pay a very high price, said Deborah Autor, Director of Compliance at FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the FDLI conference in Washington, D.C. last month. The Agency’s top priorities this year, Autor said, will be:

• Swift, aggressive enforcement action

• Civil monetary penalties

• Increased scrutiny of data integrity, global operations and unapproved drugs

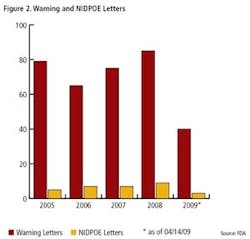

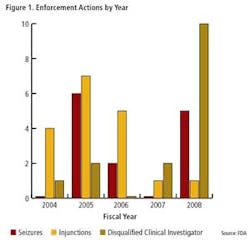

Clearly, FDA enforcement actions are on the rise (Figure 1), and the number of FDA warning letters and clinical Notice of Initiation of Disqualification and Opportunity to Explain (NIDPOE) are trending up (Figure 2). By mid-April, only four months into this year, they were already at nearly half the level of last year.

In the meantime, enforcement timelines are becoming “head spinningly” short. For instance, only a few weeks separated the last FDA inspection of KV Pharmaceutical’s manufacturing facilities and the issuance of a consent decree. This was the second consent decree that FDA issued within a two month period this year.

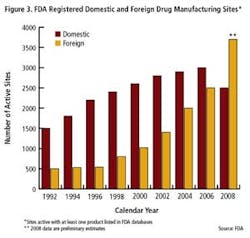

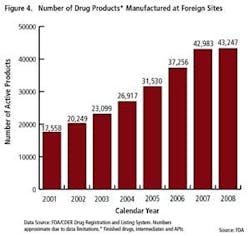

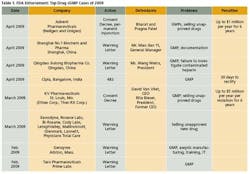

As the importance of offshore drug manufacturing centers increases (Figures 3 and 4), inspection of foreign manufacturing plants has increased dramatically this year, after the establishment of FDA satellite offices in China and India. Table 1 summarizes key enforcement activity this year, and companies in the U.S., Canada, China and India all figure into the picture.

Data integrity was seen in the Warning Letter sent last month to a Chinese heparin “manufacturer” that was actually a “shadow plant” handling materials made elsewhere.

FDA also cited its Application Integrity Policy against Ranbaxy’s Paonta Sahib plant in India, when the truthfulness of information in its drug applications came into question.

Clinical practices are undergoing much greater scrutiny, too, ever since a sting operation within the Office of Management and the Budget revealed shady practices in establishing Institutional Review Boards (IRB’s). Three weeks after a congressional hearing showed that one contract IRB had approved a fabricated study involving a fake device, FDA issued a warning letter to the company, Coast, which went out of business a few months later.

We asked consultant Michael Gregor, CEO of Compliance Gurus (Boston, Mass.) to update his last assessment and critique the industry’s FDA compliance for 2008 and 2009. Two years ago, Gregor, whose library houses extensive data on enforcement actions and regulations, cited data management, training, validation (particularly for software and IT systems), SOP writing, and process control as key problems.

Little has changed since. Below is Gregor’s assessment of industry performance in this new regulatory environment.

PhM: How has the pharmaceutical industry compliance landscape changed since we last talked?

M.G.: We’re still seeing an overall lack of production and process controls. One good example that you’ll find in many 483’s and Warning letters is failure to adequately monitor bioburden in buffers after hold times. We also see more findings involving discrepancies in manufacturing batch records for critical drug substances and drug products.

PhM: FDA appears to have been trying, via voluntary efforts and requirements, to emphasize the need for process understanding and control. Is this message sinking in?

M.G.: It doesn’t seem to be.

PhM: What are the cGMP lessons that industry still needs to learn?

M.G.: Most of those lessons center around SOPs. Companies need, first of all, to follow their own SOPs, to ensure that SOPs are adequate to cover disparate processes, and ensure that employees are properly trained if processes and SOPs change. These themes run repeatedly in 483’s that FDA has issued over the past three years

PhM: What’s wrong with the SOPs? Are they too difficult for operators to understand?Or are they too superficial?

M.G.: It’s a compilation of issues. First, you have contractors or employees writing SOPs without the specific process knowledge. Ideally, users should write the SOPs themselves since they carry out the relevant operations each day and have the most experience.

But even where SME’s are writing the SOPs, I find that they’re often writing them so vaguely that different employees end up carrying out same process indifferent ways. For FDA inspectors, this signals that an organization is out of control.

SOPs call for stronger language.

PhM: Do they contain enough detail?

M.G.: Many companies write SOPs at a high level, and put all of the detail in work instructions. This practice makes it very hard for employees to figure out what to do. In general, SOPs need to be short and to the point, and written by the people closest to the process involved.

PhM: What are the key words to use and avoid?

M.G.: Direct is good, so words like “must” are required rather than the waffling “perhaps,” “should,” “may,” or “depending on”

PhM: What’s wrong with the way that pharmaceutical companies are setting up their quality control departments?

M.G.: Some companies are not utilizing QC departments adequately, and not ensuring that these departments have the resources that they need. Often, SOPS are written specifically to exclude the Quality Control department, because operations and manufacturing are afraid of bottlenecking processes. As 483’s show, predicate rules specifically call out need for quality control systems and there have been a lot of FDA citings that single out SOPs as they pertain to the responsibility of the QC unit.

PhM: What needs to happen? Are the wrong people, or those with the wrong type of training, working in QC?

M.G.: More staffing is needed for QC. There’s an ever running problem of QA and QC employees not having enough technical knowledge to be able to review and understand manufacturing batch records for drug products or substances, either for clinical or commercial scale supply. This lack of knowledge is also seen with computer systems validation.

PhM: How are companies doing where validation is concerned?

M.G.: I‘ve seen several companies either fail to properly validate their manufacturing systems or to validate at all. Many make mistakes occur when validating both manufacturing equipment and systems. Companies seem to struggle with where to begin their validation process and to what extent to perform validation, therefore, leading to insufficient validation evidence.

PhM: How can that be? Isn’t approval contingent upon validation?

M.G.: In theory, yes, but FDA inspectors aren’t always careful in assessing equipment or systems validation. It seems FDA inspectors focus more on process validation as opposed to equipment and computer system validation. However, this may change, as a significant increase in the FDA budget will allow for more investigators.

PhM: Do you think that FDA’s draft guidance on process validation will change that, and also change industry response? Are inspections being handled differently now, embodying concepts of 21st century GMPs?

M.G.: No, I still see FDA inspectors coming that know nothing about the respective industry---for instance, microbiologists evaluating manufacturing operations or diagnostic imaging centers used for clinical trials.

PhM: As far as IT validation is concerned, are GAMP documents helping?

M.G.: No. Neither GAMP nor ISO standards are law. GAMP is an industry reference, ISO is a standard. They’re great starting points, but people are using them as if they were the law. When FDA shows up at your door, they won’t care whether you used a GAMP or ISO model for IT systems validation. They’re going to care whether records are maintained in a validated system to operate as intended. That’s a huge problem.

PhM: Can you point to any glaring examples of validation omissions as lessons?

M.G.: Companies are failing to define system requirements, and they aren’t testing to ensure that the requirements of the system are being met. If you don’t have good requirements that define what a system is going to do, and you don’t test your requirements and then trace them, you won’t have a system that operates as intended. Companies must ensure their respective systems operate as intended, as the FDA requires companies to do so. If you’re maintaining records as required to be maintained by CFR Parts 210 and 211, you had better perform your system validation to ensure data integrity and patient safety.

PhM: Outside of GMP, in the clinical area, what are the biggest issues?

M.G.: Integrity of IRBs is a major problem. The second issue is outsourcing of clinical trials and noncompliant CRO’s. Contract companies often fail to validate computerized systems, and companies are failing to adequately audit their CRO’s.

These CROs are failing to validate systems and train employees. They’re also, in some cases, double verifying data, so the same person that entered data is verifying it. This is very scary, when you consider the validity of data and the safety of the world drug supply.

PhM: Overseeing contractors seems to be a problem across the board, from research to manufacturing. FDA has published Quality Systems guidance. Is anything missing from that guidance, why are there still problems?

M.G.: A lot of the independent contractors I’ve seen don’t have experience for a particular position and companies don’t want to spend on training.

PhM: Is this also a reflection of hiring practices and the way HR departments are run today? We hear that most HR is now being outsourced.

M.G.: Over the past six years, staffing firms have been handling more placements, as many companies are outsourcing. Jobs are constantly posted on sites like Dice or Medzilla, and hundreds of resumes are received. Staffing firms then do a very general search using key words such as Part 11, quality, or validation, and pick up a number of resumes. The problem is that the client often needs much more specialized knowledge, so they end up with someone who is “on the fence.”

Staffing firms who call about specific jobs and read the requirements right from a job description from the client always surprises me, as it’s clear that they have absolutely no idea what the terms mean. Unfortunately, these people gain access to client sites to get their requirements so what ends up happening is Pharma companies get a pool of sub-par candidates to chose from. Ultimately, what clients end up with is a mismatch for key quality positions that impact data integrity, patient safety and welfare. Very unfortunate for consumers.

PhM: We hear that companies aren’t vetting CROs and CMO’s sufficiently. What are you seeing?

M.G.: One consistent issue I see is inexperienced people performing audits. It takes someone with many years of years experience (minimum 10-15 years) to have a true understanding of what to look for. Not to knock entry level people, but you should not send them alone to conduct an audit, and I’m seeing a lot of that. Inexperienced auditors cannot effectively audit when they are unfamiliar with terms like systems validation, data entry verification, or randomized double-blinded studies. I always suggest that inexperienced auditors need to go along with an experienced auditor in order to learn how to audit more effectively over time. Many CRO’s and CMO’s are non-compliant with federal requirements, therefore, posing a significant risk to patient safety. Unquestionably, this is one of many areas FDA investigators need to spend more time.