What once felt like a faraway threat has become an imminent crisis.

Metaphorical warnings about melting ice cream cones have become quite literal in the last few years, with record-breaking temperatures and climate change-induced events happening all over the world.

Our planet is sick, and inevitably, so are we.

The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report estimated that half of the world’s population is threatened by water shortages; extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and severe; and more than 14% of the world’s species are at high risk of extinction as global temperatures rise.

In the U.S. alone, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that there were 20 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in 2021, just two events shy of the record set in 2020. These events caused at least 688 fatalities and scores more injured.1

Last November, a Canadian woman in her 70s became the first person to be officially diagnosed with ‘climate change.’ Earlier in 2021, Canada went through a record-breaking heatwave that killed at least 500 people and worsened air quality over 40 times what is normally accepted — which the patient’s doctor decided was to blame for her ailments.

And just like this climate change-induced health crisis can no longer be ignored, our role in the deterioration of our environment can’t be diminished. According to the Lancet Countdown, an annual study that looks at the impact of climate change on human health, these heatwave events “would’ve been almost impossible without human-caused climate change.” 2

We have no choice but to fix what we have broken, and the road to healing our planet is long. This journey toward a greener future is one we must all take together, and manufacturing industries play a big role in the solution.

Research sites and manufacturing facilities can be among the highest energy consumers, doubling the resource consumption of corporate office space. A recent study found that the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry is spending more than $1 billion on energy consumption every year — and generating 55% more emissions than the automotive industry.3

Pharma’s road to sustainability comes with unique challenges, but in the end, the industry’s efforts will have a big impact, inspiring sustainability throughout the supply chain.

First stop: corporate responsibility

Deciding to embark on the journey toward sustainability is a decision made by everyone getting in the car. And the pressure to start driving comes from regulatory and legislative accountability, at least initially.

Adopted in 2016, the Paris Agreement is an international treaty on climate change signed by 196 countries committed to working toward the long-term goal of keeping the rise in temperature below 2°C, which would require emissions to be cut by roughly 50% by the end of this decade. This global accountability trickles down to local governmental and regulatory agencies alike, ultimately becoming an issue of compliance for the pharma industry.

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency outlines several laws and regulations that the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector must abide by. These cover general compliance guidelines like the Inorganic Chemical Manufacturing Statutory and Regulatory Summaries and include resource management guidelines specifying air, waste and water regulations.

But having to comply with stricter environmental regulations is not the only thing nudging pharma companies to go greener.

“There is growing pressure to pay more attention to sustainability,” says Thermo Fisher’s Chris Williams, vice president of Engineering Technology, Operations and Innovation for the company’s Pharma Services Group. “What I like about the pressure is there’s passion in the people that are trying to figure out how to really affect the carbon footprint.”

The pressure, Williams says, now comes from multiple sources, all the way from stakeholders to Thermo Fisher’s own employees. “Corporate social responsibility has grown, and maybe we were headed that way before COVID,” says Williams.

More recently, Thermo Fisher committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, in addition to their earlier goal to reduce carbon emissions by 30% by 2030.

Williams adds that, as the world slowly returns to normal, people and companies alike are more mindful of their impact. “There are more and more companies rightfully making the proper commitments and holding each other accountable.”

For Germany-based global CDMO Vetter, a company with a long history of environmental stewardship, accountability is inextricably linked to company reputation. In 2020, all of Vetter’s European sites became carbon neutral, an effort that had been underway since 2014. Social commitment is a part of the company’s core values, with a focus on looking beyond the products and services offered to recognize their impact.

“When considering the benefits associated with sustainability practices, it is important to realize that successful companies have reputations to uphold. They are expected to not only be financially stable but also socially responsible,” says Henryk Badack, senior vice president, Technical Services/Internal Project Management at Vetter.

Badack emphasizes that companies are expected to act in a sustainable manner and to do all they can to support the environment. “That means using natural resources whenever possible and meeting high ethical standards. Being sustainable means adopting a culture of responsibility. It is important that companies make every effort to live within the earth’s natural restrictions and accept the boundaries and limitations of its ecosystem,” he says.

And while pharma has a good track record of corporate environmental stewardship, with companies like Roche consistently ranking as one of the most sustainable companies in the world and other pharma giants like Pfizer and Bayer leveraging green chemistry to reduce their global carbon dioxide emissions greatly over the last few years, sustainability specifically within manufacturing is driven by a different force and is a distinctive beast to tackle.

Defining ‘sustainable’ facilities

Sustainability is more of an umbrella term — a catch-all word used to discuss a very broad concept that can be applied to almost any aspect of any industry. But within pharma manufacturing, going toward sustainability has become nearly synonymous with moving toward efficiency.

“When you talk about sustainability, at least through our lens, it’s about how you maximize efficiency in the resources that you use,” says Jeffery Odum, CPIP, practice leader for ATMP and Biologics at Genesis AEC, a full-service project delivery firm providing expert architecture, engineering, construction management, commissioning, qualification, and validation for pharma companies.

“Environmental sustainability and the environmental constructs of a building are a natural outfall of what we consider to be efficient to design-build,” says Odum.

This intrinsic relationship between sustainability and efficiency allows for specificity in goal outlining.

“Sustainability within the manufacturing facilities is a system engineering formula,” says Ken Anthony, vice president and Life Sciences Division leader at Haskell, which was ranked No. 1 by Engineering News-Record among green design firms and green contractors in the manufacturing and industrial sector.

“If you can make the summation of all the systems and subsystems that go into manufacturing equal zero and still produce what you want to produce, that is considered a perfect system,” continues Anthony.

According to Anthony, the most widely-used evaluation grid for this ‘perfect system’ and efficient design-build is Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED). “LEED is the gathering point for architects, engineers, instructors, and clients,” says Anthony.

Within the LEED building evaluation system, there are 100 possible base points given across five categories including site sustainability, water efficiency, energy, atmosphere and material resources, as well as indoor environmental quality. Additional points are given for innovation in design and regional priority.

Not only is sustainable design measurable through a LEED score, but there is also a quantifiable benefit that can be calculated. Resource management affords manufacturing facilities the ability to say, “if I cut my energy utilization or water utilization, or increase water reuse, there’s a formula or an actual dollar amount the company can determine,” Anthony says. And this dollar amount is an important incentive to know.

“Clients want as much volume in a building they can get per dollar,” Anthony adds. “We start at the beginning phases of a new facility, and as design-builders, we are in the mode of getting our clients the most efficient, operational facility, keeping the summations formula in mind.”

As green energy sources have become more available, affordable and better, sustainable practices and pharma manufacturers getting ‘the most bang for their buck’ have grown synonymous. Efficient sustainable design is on its way to becoming the best for both worlds.

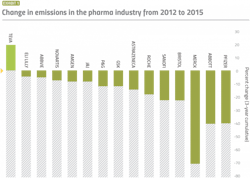

A study published in 2015 that examined the carbon footprint of pharma companies over four years found that Roche, J&J and Amgen all showed very significant increases in revenues amounting to 27.2%, 25.7% and 7.8% respectively between 2012 and 2015, while still managing to reduce their emissions by 18.7%, 8.3% and 8% respectively during that same period.3

Plant floor sustainability

For pharma, adapting to more stringent regulatory requirements has also resulted in more efficient, sustainable facilities.

At their core, according to Odum, good manufacturing practices are about protecting the product. Pharma manufacturers are using technological advances to reevaluate their approach to quality practices. On the facilities side, scientific advances have enabled the industry to shift from focusing on classifying a space to protect the product, to closing the manufacturing process instead.

The latest global regulatory guidance — the new PIC/S Guide to Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Product Annexes — is now focused on process closure to reduce risk. Closing the process means that pharma manufacturers are operating to ensure that the product never comes into contact with the environment, operators or contaminants. And if you can prove that, the space itself is not as critical as it was previously.

Odum adds that there is a direct relationship between the requirements for classified space and more efficient facility design.

“If you can close a system now, going back to the definition of sustainability, suddenly you can reduce electricity consumption or the amount of air that you’re moving. You can really make your asset so much more energy efficient. And, it’s not because you purposefully went out to try to reduce your carbon footprint, right? You’re doing it because you’re protecting the product and you’re gaining an advantage from that,” says Odum.

Vetter’s largest sustainability project was also motivated by the pharma industry’s increasing regulatory requirements. In 2017, the company expanded its Center for Visual Inspection and Logistics located in Ravensburg, Germany in order to bundle capacity for final product inspection and logistics at one site. This came in response to tightening requirements for final product inspection as well as for transportation and storage of pharmaceutical materials.

The site, which won the coveted ISPE Facility of the Year Award in 2018 as a ‘Facility of the Future,’ includes an environmentally friendly block heating and power plant, the use of geothermal energy, the comprehensive use of excess energy, as well as photovoltaic systems.

Bumps on the road

For pharma, the road to sustainability is certainly not without obstacles.

“The very nature of our business means we face significant challenges since the production of medicine is resource-intensive,” says Badack. “Furthermore, due to the required high standards and strict, ever-increasing regulations by health care authorities, it is difficult to entirely avoid residual emissions.”

Pharma manufacturers often find themselves in a balancing act, trying to make the ‘formula’ stay as close to zero as possible, without making environmental trade-offs.

Sustainable choices within manufacturing facilities are addressed at one of two stages, Williams says.

One of them is the conception stage, with the support of firms like Haskell and Genesis, where green design and building ensure a sustainable facility from conception. On the other hand, once a manufacturing facility is operational, options can be more limited.

A powerful way in which existing pharma manufacturing facilities have joined on the journey is through outsourcing of resource management.

By building integrated interdependencies, Thermo Fisher has worked together with a third-party, fixed facility to manage solid waste in selected New England facilities as zero waste, where at least 90% of the generated waste is recycled. Collectively, Thermo Fisher’s certified zero-waste sites have saved almost $7 million between 2012 and 2019.1

SAK Environmental, an environmental consulting company, performed a third-party audit and certification of Thermo’s Bedford, MA campus, a site that performs manufacturing, research & development of life science products. Every month, SAK ensures that up to 9 tons of waste are managed, including general waste, e-waste, drums, labware and residuals.

“We’re trying to get any expertise and help that we can find. We don’t always have the solutions. All these businesses must run, and some parts of the business are larger than others. The more we can look for where people have already solved the problem, the better,” says Williams.

Operating manufacturing facilities can also incorporate sustainability when making equipment decisions. Many pharma companies have turned to secondhand suppliers for help repurposing machines already in their network or to find used equipment that can be decontaminated and brought back to the GMP environment.

An added and unexpected benefit from purchasing used equipment, says Justin Kadis, Business Development Director at Federal Equipment Company, has to do with timelines.

“Original equipment manufacturers can give timelines between 12 or 18 months for a new machine. Whereas if they were to buy it used, it can be shipped and utilized within days,” says Kadis

He adds that this growing focus on green and circular economy from a facilities standpoint has made used machinery a more approachable option for larger pharmaceutical manufacturers. “In the past, big pharma tended to sell us the machines and we used to then sell those machines to contract manufacturers or generics manufacturers. Now, given the timing, they’re taking a harder look at used equipment and asking if it can serve any function within their network,” notes Kadis.

Even if a piece of equipment is not rebought or become outdated, companies like Federal Equipment help ensure a green journey all the way through its life.

“Even if it’s the worst-case scenario, we still have the capability to take a machine and try to salvage as much as possible, either by refitting, dismantling for parts or scrapping for metal,” says Kadis.

Hope ahead

Amid the global discourse of despair over climate change, pharma has paved a hopeful road. Through climate mitigation all the way throughout the manufacturing facilities — from design to machine scraps — sustainability can reap benefits for companies and the planet alike.

Williams predicts that looking ahead, sustainability discussions within the pharma industry will take a wider perspective, with more attention being paid to the supply chain and its interconnectedness.

“How do we share scope three responsibilities across a globally integrated supply chain? It’s a challenge,” says Williams, referring to the Green House Gas Protocol. The protocol establishes globally standardized frameworks to measure and manage greenhouse gas emissions from private and public sector operations, value chains, and mitigation actions.

Emissions are categorized into three scopes. Scope 1 is direct emissions from facilities, scope 2 emissions are those made from purchased electricity and steam, and scope 3 includes all indirect supply chain emissions.

At the same time, Williams hopes that technology improvements will continue to allow heavy facilities to be greener.

“It’s easier to make an office building green. Depending on the part of the climate, maybe you have solar, maybe have a wind farm. But technology improvements are needed so that we can make the right choices for the heavy part. How do we share scope three? And how do we evolve some technologies for the heavier side biological pharma manufacturing?” Williams adds.

Just like the journey up until this point, overcoming these future challenges will continue to require collaboration between all experts ensuring sustainability conversations at every step of every new and existing manufacturing facility site.

Badack reiterates the importance of collaboration between all pharma stakeholders as the way through the climate crisis.

“For many companies in our industry, achieving an efficient contribution to the sustainability effort is paramount. While this will require some investment, it will help ensure long-term, stable growth and profits. Biopharma companies, suppliers, and CDMOs should continue working together toward sustainable solutions,” says Badack.

“When you die, you hope that with your last breath you know you’re leaving the world a better place,” Anthony adds. “I think in our generation, we’ve become aware of the vastness of the pharma industry and how it takes a whole village to think about creative solutions for efficient builds and overcoming the roadblocks to sustainability.”