Dismantling the Gray Maze

By Agnes Shanley, Editor in Chief

Japan’s pharmaceutical market may be the world’s second largest, but, until recently, only the most persistent of optimists hoped to do much business there. Drug approval requirements, among the most stringent in the world, drove many foreign drug manufacturers away, leading some to focus their efforts elsewhere in Asia. As a result, the supply of pharmaceuticals approved for sale in Japan still lags several generations behind what’s available in the U.S.

If the term “risk averse” sums up the U.S. drug industry, it’s even more applicable to Japan. Lawsuits may be unheard of, but any Japanese citizen can launch a product recall or bring a drug company to its knees, simply by going to the press with a complaint about a serious adverse reaction, which they assume to be linked to a drug.

In this closed environment, it could be very difficult for foreign companies to understand the context behind feedback they would receive from MHLW, or to grasp the basis for regulatory hurdles, says Sue James, vice president of worldwide regulatory affairs, compliance and quality for GlaxoSmithKline in Parsippany, N.J. There was an unwillingness to challenge the existing paradigms, she says.

Cultural issues

Of course, cultural challenges compounded the difficulties, as well as the subtlety of the Japanese language. An interesting example is the concept of “elegance,” so pervasive in Japanese culture, which has led some Japanese reviewers to reject up to 40% of foreign made materials. Even a microscopically small speck on a tablet that has passed all quality and safety tests in the U.S. and Europe may be deemed unacceptable in Japan, says Dr. Ulrich Taglieber, an independent expert on Japanese pharmaceutical regulatory affairs, and former VP of international regulatory affairs for Merck.

This attitude can extend to inspections and documentation, too. “Six minor typos or errors in a 50-page document can lead some Japanese officials to describe the document as ‘seriously flawed’,” he says. “Japan would like to assume 100% inspection of everything, and achieving that final 4% of perfection can take as much effort as the initial 96% did.”

Within the past few years, the U.S. FDA has, at least, articulated a more scientific and risk-based framework for drug regulation. Experts say that Japan could benefit from such an approach. However, they agree that Japan has already made tremendous progress in a very short time, opening up what had been a closed and highly protected industry.

A black box

To appreciate the changes that have taken place within Japan, one must go back to the 1980s and 1990s, Dr. Taglieber says, when Japan was “running on its own separate rail.” Foreign drug companies hoping to sell pharmaceuticals in Japan had to duplicate all Phase I through III data in Japan, on Japanese subjects.

“At that time, the consultation process was essentially a black box,” Taglieber says. “You threw a new Japan-specific drug application file into the system, and, a year and a half later, you received an oral pronouncement attributed to the Agency’s expert reviewers, all in Japanese. You’d have to get a stenographer to take down the pronouncements, literally, at an expert’s door. Sometimes you interpreted them correctly. Sometimes you didn’t.”

The conduct of clinical trials in Japan was another issue. The trials themselves were often dominated by investigators rather than by the scientific focus of the sponsors. Often they were poorly organized and inefficient, so that the output was quite unpredictable, Taglieber says. “You could have as many as 150 or more investigators for a single trial, each covering one or two patients.”

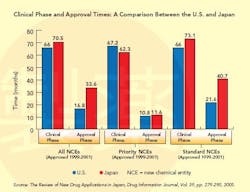

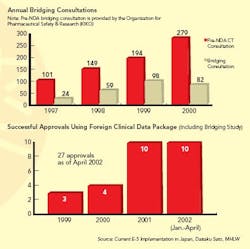

This situation changed dramatically in the 1990s (see Graph below), a decade that saw the establishment of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH), whose goal is to standardize and coordinate efforts between regulatory bodies in the world’s three largest drug markets: the U.S., Europe and Japan.

In 1997, Japan established new guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), based on ICH standards, which brought “structure, science and rules” to the process, Taglieber says, setting guidelines for informed patient consent and monitoring. A year later, it adopted ICH’s E-5 standards, designed to reduce the unnecessary duplication of clinical test data. Guidelines for E-5 are a bit vague, however, and the acceptance of foreign data continues to be a major point of contention (see CLINICAL TRIALS AND E-5, below). Nevertheless, from this point on, Japan no longer required that all trial data be duplicated. For many foreign firms, this was a major step forward, and earnest discussions with sponsors began to take place.

In 2002, another turning point came when the Ministry issued a “pharmaceutical vision statement,” acknowledging the need for the Japanese regulatory environment to change and for the Japanese industry to become more competitive, internally and globally.

PMDA is established

The following year, the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law restructured Japan’s regulatory framework, establishing the Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices Agency, an independent, nongovernmental agency separate from MHLW, and making ICH’s voluntary principles part of national law.

These changes are starting to increase access to the Japanese market. They’re also beginning to bring greater alignment for chemistry manufacturing and control (CMC) and clinical process development, says GSK’s James.

“The new Japanese Agency has much more of a scientific focus than the old,” says Taglieber. “They’ve focused on recruiting more Ph.D. biologists and M.D.s, and have established a structure where teams review therapeutic data. Now interaction is not only possible, but consultative discussions are invited, and written communication is the norm.” PMDA has also hired two statisticians.

Further progress is needed, argues Dr. Osamu Doi, who has worked for both MHLW and PMDA, and is now senior executive director of the Society of Japanese Pharmacopoeia (see A NEW DAY FOR JAPANESE PHARMA, below). And some obstacles preventing ICH’s global vision from taking shape may originate outside of Japan. “Japan is increasingly keen on harmonization and developing agreement with regulators such as the FDA, but the FDA isn’t always in the best position to cooperate,” says Paul Hajdukiewicz, a GSK regulatory affairs executive based in the U.K. “When I asked one FDA official whether the dialogue between FDA and EMEA had extended to MHLW, it was clear it had not,” recalls his U.S. colleague, vice president Sue James.

However, experts agree on the issues that remain. Number one is speed and transparency of approvals. “We need better transparency and predictability within PMDA, particularly for clinical trials, consultation advice and review,” says Taglieber. “They’ve made great headway but still ‘veil dance’ on some issues, giving us much more data than previously, but not the individual data points, so it’s often difficult to analyze what their detailed performance is.”

“There are separate approval paths for locally manufactured versus imported products, and for in- versus ex-monograph products,” says David Parsons, director of international regulatory affairs for GSK’s consumer heathcare R&D, based in the U.K. Although manufacturing and product approval are now being unified, there may still be a need to repeat some preclinical and clinical activity. In addition, a lack of harmony between pharmacopoeias (USP and organizations in Japan) can add further delays. In general, it can take a very long time to get approval if you are out of an existing monograph, says Hajdukiewicz.

The practice of rotating MHLW reviewers every two to three years has led to a lack of “institutional memory” and inconsistency, Taglieber says. Expert reviewers are drawn from the National Health Institutes, Cancer Centers and other government agencies and assigned to a review team. “It usually takes them 1 to 1.5 years to get up to speed, and once they’ve mastered the intricacies, their rotation is over,” Taglieber says, “and the next reviewer assigned to the team may not agree with their decisions.” This is difficult for sponsors to cope with.

Even within PMDA, earlier, faster consultations are needed. “Regulators in Japan must accept the fact that, initially, only minimal data will be available, just as FDA and other agencies do,” Taglieber says. Some observers note that, at times, the relationship between the private PMDA and the government-run MHLW has appeared to be somewhat “adversarial.”

Whatever obstacles remain, it is clear that Japan’s regulatory agencies are serious about change, GSK’s James says. “We know that science will prevail,” says Taglieber. “We’ve seen tremendous progress in eight years,” he says. “The spirit for change is there at the top levels of Japan’s regulatory organizations, although it may take another five years to reach the next level.”

A NEW DAY FOR JAPANESE PHARMA:

|

CLINICAL TRIALS AND E-5

Japanese clinical trials, which cost roughly three times more, per patient, than they do in the U.S. or Europe, have been a sticking point for most foreign drug firms doing business in Japan. When Japan officially embraced ICH E-5, it agreed to allow the use of foreign clinical trial data in drug approval applications. In fact, though, Japan had already agreed to do this back in 1986 when it signed the Market Oriented, Sector Selective (MOSS) agreement with the U.S.

Osamu Doi, Ph.D., opened up scientific discussion within ICH about whether Japanese data were always needed. Ultimately, Japanese experts agreed that variations between individuals within the same ethnic group were more significant than those among different races, but they did not agree that all parts of clinical trials could be waived on this basis. “In early discussions, they agreed to waive some Adsorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion (ADME) studies, but not the more expensive Phase II and III studies” says Dr. Wen-Hua Kuo, an MIT scholar who has studied E-5 extensively. In 2003, they took a more restrictive position.

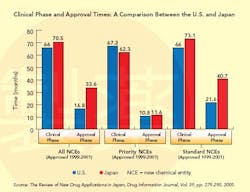

When a drug is suspected of having different effects in the Japanese population, ICH approves the use of “bridging studies” (see Graphs below) to extrapolate findings from foreign clinical trials. The concept of bridging, itself ambiguous, may have only widened the divide between the West and Japan on the subject of clinical trial data validity, says Kuo. Western firms view bridging as a valid way to determine whether more-limited Japanese clinical studies will suffice. Some Japanese regulators, however, see it as a compromise.

Fundamentally, Kuo says, it is a philosophical question: “The West believes in primary unity among races while Japan appreciates the diversity. But, so far, each side has failed to convince the other, fully, of the scientific merit of its arguments.”

Could pharmacogenomics provide a neat answer to all these issues? “It just opens up another box,” says Dr. Ulrich Taglieber, former VP of international regulatory affairs with Merck. “You still need clinical trial and population kinetics data.”

Yet, conditions appear to be changing. Six years ago, AstraZeneca had several products approved in Japan without clinical trials. GSK has also successfully used U.S., European and international clinical data in applications in Japan, says regulatory affairs VP Sue James. However, Wyeth is assuming the need for Japanese clinical trials, and has significantly increased the number of clinical trials it is conducting in Japan, and running them in parallel with, rather than after, trials in the U.S. and Europe: 12 Wyeth compounds are now in Phase I in Japan, seven are in Phase II and six are in Phase III, running the gamut from oncology to cardiovascular and neurological treatments to a pediatric vaccine.

LINKS TO RELATED MATERIALSState and Race in the Genomic/Global World, by Dr. Wen-Hua Kuo The Japanese Pharmaceutical Revolution, by Rafizadeh-Kabe and Fike Clinical Relevance of Ethnic Factors: A Simulation Study, by Wang, Ou, Chern and Lin The Review of New Drug Applications in Japan: The Decline in Approval Times After the Introduction of an Internalized Review System, by Ono, Yoshioka, Asaka and Tamura The Current Status of Clinical Trials in Japan, by Takeyuki Sato |