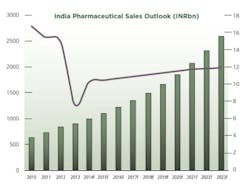

2013 was a challenging year for pharmaceutical firms operating in India. Data from primary research firm AIOCD Pharmasofttech AWACS showed that pharmaceutical sales grew by an average 5.7% in 2013, a far cry from the average growth of 15.3% recorded in 2012. A number of factors have led to the decline in attractiveness of the Indian pharmaceutical market.

DRUG PRICE CONTROL ORDER (DPCO) 2013

In May 2013, India’s Department of Pharmaceuticals released a Drug Price Control Order (DPCO), reducing the prices of 348 drugs included in the essential drug list as part of the government’s aim to make healthcare affordable for the country’s vast 1.2 billion population. The DPCO was cited by Wockhardt, Ranbaxy and Dr Reddy’s Laboratories as a challenge to their financial performance. Furthermore, in January 2014, Alok Sonig, senior vice president and India Business Head (Generics) of Dr Reddy’s, stated that the firm’s revenues for 15 to 20 drugs will be affected by the DPCO, leading to a 5% overall decline in the firm’s revenues in the country.

CLINICAL TRIALS HALTED

The stopping of clinical trials has been partly due to lax regulations, deaths and other serious adverse reactions, which were not properly reported. Between 2005 and 2012, a total of 2,868 deaths were linked to clinical trials, with 89 of the cases attributed directly to trials — although compensation was only paid to 45 of these victims. Amendments were subsequently made in January 2013 to the Drug and Cosmetics (Third Amendment) Rules 2013 to safeguard patient safety in clinical trials. Following this, in September 2013, the Supreme Court halted clinical trial approvals in the country, stating that there were no comprehensive rules available to regulate the sector. At the time of writing, the country has yet to approve any new clinical trials.

This essentially means that India has halted approval of clinical trials for approximately a year. This has a significant negative impact on pharmaceutical firms that are looking to launch new drugs in the country, affecting revenues and overall sentiment towards this once very promising emerging pharmaceutical market.

2013 was a confusing year in terms of understanding India’s position on intellectual property protection. In March 2013, the country rejected Novartis’ appeal for patent protection for Gilvec (imatinib), ending a seven-year patent conflict. However, in the following months, it rejected compulsory license applications for various drugs, including Roche’s Herceptin (trastuzumab) and Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Sprycel (dasatinib), as well as upholding the patent granted for the original compound, laptinib, of GlaxoSmithKline’s Tykerb. The country’s less aggressive stance on patent protection spells good news for multinational pharmaceutical companies, although the situation may reverse, given the high cost of innovative drugs.

INTERNATIONAL MARKETS FOR GROWTH

Business Monitor International finds that several domestic pharmaceutical companies are well placed to limit the negative impact of uncertainties in the domestic pharmaceutical market, given that the majority of their revenues are generated overseas — particularly in developed states in the U.S. and Europe. However, even the international market is proving to be challenging for some Indian domestic companies, due to disparities in manufacturing standards. This is particularly so for Ranbaxy; the company’s conflict with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) places it at the center of the issue:

January 2013: The U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) filed a consent decree of permanent injunction against Ranbaxy. The decree required the firm to comply with detailed data integrity provisions and prevented Ranbaxy’s drugs from entering the U.S. market. The generic drugs in question were manufactured at Ranbaxy’s facilities in Paonta Sahib and Dewas, India, including drugs such as Sotret (isotretinoin), gabapentin and ciprofloxacin.

May 2013: The firm pleaded guilty to felony charges relating to the manufacture and distribution of certain adulterated drugs made at two of Ranbaxy’s manufacturing facilities in India. Ranbaxy also agreed to pay fines totaling $500 million. The investigation dated back to the period immediately before Ranbaxy was acquired by Daiichi Sankyo, in mid- 2008.

September 2013: The FDA issued an import alert on products manufactured at Ranbaxy’s Mohali plant in India until the company complies with U.S. current GMP standards. The agency identified “significant cGMP violations” at the facility during inspections in September and December 2012, including the firm’s failure to “adequately investigate manufacturing problems.” During the inspections, the FDA found a black fiber in a tablet that could be a human hair.

Despite promises by Ranbaxy and its parent company, Daiichi Sankyo to improve manufacturing standards, in January 2014, the FDA issued Form 483 to the firm, indicating that its investigator(s) have observed potential violations of the U.S. Food Drug and Cosmetics Act at its active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) plant at Toansa, India.

In addition to the FDA actions against Indian pharmaceutical firms, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is increasing its scrutiny of potential manufacturing non-compliance in firms producing generic drugs. In December 2013, the FDA announced that the EMA, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK will work together on joint inspections globally to ensure that generic medications are safe and effective. Given that India is a global powerhouse for generic drug production, the country will see increased scrutiny in its drug manufacturing process. Companies that are unable to fulfill criteria laid out by the two regulatory authorities will lose out on the rising demand for generic drugs in the United States and Europe.

Business Monitor International holds a relatively neutral view on India’s domestic pharmaceutical sector, given that pharmaceutical growth rebounded from negative territory (between September and October 2013) to relatively healthy numbers in November (+6.9%) and December (+8.2%). This potentially suggests that the effects of the DPCO 2013 will wean off slightly in 2014. However, extensive bureaucracy remains a key downside risk to the pharmaceutical industry’s growth potential.