By the start of the millennium, it was becoming clear that the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry was not modernizing as quickly as other industry sectors. Recurrent drug shortages posed a chronic threat to the U.S. health care system and reflected this general lack of manufacturing modernization.

At the same time, scientific breakthroughs and increasing globalization of drug manufacturing placed new pressures on regulators. Regulatory policies fragmented the approach to pharmaceutical quality regulation and entrenched a dichotomy between pre-market and post-market oversight. The bedrock of pharmaceutical quality regulation was then — and still is today — current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) requirements, which define the manufacturing standards to legally market drug products in the U.S.

As humanity hopes and prepares for the start of a post-COVID world, it may prove valuable to reflect on the start of the post-9/11 one. Twenty years ago, the U.S. was newly involved in a global war on terror, a relatively unknown Tom Brady had led his team to its first Super Bowl victory, and newly-launched Pharma Manufacturing magazine published an article focused on a then-new “ambitiously titled” FDA report, “Pharmaceutical CGMPs for the 21st Century: A Risk-based Approach.” This report emphasized the importance of considering risk but represented only a start to the agency’s overall effort to confront the diverse problems facing the pharmaceutical sector.

A more comprehensive vision emerged within FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and culminated with the launch of the Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (OPQ) in early 2015. CDER designed this new ‘super office’ to integrate assessment, inspection, surveillance, policy and research across all sites of manufacture — domestic or foreign — and across the life cycle of all human drug product areas: new drugs and biologics, generics, biosimilars, over-the-counter drugs and certain compounded drug products. Today, OPQ continuously monitors the state of quality for an active catalogue of over 4,500 sites and over 150,000 products and provides a yearly public report on the state of pharmaceutical quality in the U.S.

The discussion of pharmaceutical CGMP 20 years ago centered on satisfying compliance standards for material systems, equipment and facilities, production, laboratory, packaging and labeling — standards that set only a threshold for in-house quality systems. Forward-looking companies, and the FDA, understood the importance of transitioning from routine compliance with CGMP to systems that reflect wider philosophies of continual improvement and quality management. Manufacturing in the landscape of constant technological advancement requires a commitment to quality, thoughtfully designed quality management systems, and the adoption of mature quality management practices. To avoid problems, smart manufacturers conduct robust pre-market product development and continually improve their processes to foresee emergencies, reduce the likelihood of quality-related supply disruptions, and promote innovation. Due to this, over the past two decades smart pharmaceutical quality regulation has evolved beyond focusing on simple compliance with CGMP and toward a more holistic, pragmatic and proactive regulatory approach.

Quality culture drives continual improvement

This full history of pharmaceutical regulation has focused heavily on data collection prior to marketing approval and reactive and punitive measures if problems occur. The FDA vision for the future of drug manufacturing focuses on the development and evaluation of quality management practices and the quality culture needed to foster continual improvement. Much research now supports the fact that sites with more mature quality practices better anticipate and resist supply chain disruptions. A high degree of quality management maturity has a positive impact across an organization, including on the company’s fundamental ability to deliver supply to patients. A focus on quality management practices empowers manufacturers to identify ways to improve the effectiveness of their quality systems, realize available regulatory flexibilities, and improve their overall process capability.

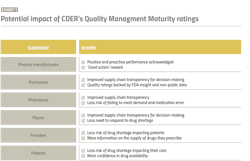

The FDA has proposed the development of a system to objectively rate the quality management maturity of manufacturing sites that will help incentivize drug manufacturers to achieve maturity at facilities around the world (Exhibit 1). A rating system will allow regulators and purchasers to gauge the performance and robustness of drug manufacturing facilities based on their quality practices. CDER cannot evolve to a more proactive regulatory stance without also changing the type of data it receives. More information on quality management will provide a real-world basis for better applying regulatory resources; that is, applying less regulatory oversight in places where it is not justified based on the potential value it brings to patients and consumers. FDA does not seek more data to expand regulation; rather, more data enables FDA to focus regulation on the most appropriate areas of the site and product catalog.Bringing emerging technologies into pharma manufacturing

On a long enough timeline, continual improvement requires the adoption of new manufacturing technologies and approaches. Emerging technologies promise to transform manufacturing practices and improve patient access to therapies. However, manufacturing innovations often present unprecedented technical and policy challenges for manufacturers and regulators.

In 2014, CDER established an Emerging Technology Program (ETP) to encourage early interactions between technology developers and FDA scientists. CDER’s ETP now provides a venue for stakeholders to discuss and resolve potential technical and regulatory issues related to new technologies prior to filing a regulatory submission. As of today, the program has facilitated over 150 meetings with stakeholders who are pioneering or adopting emerging technologies.

Of course, a technology cannot remain ‘emerging’ forever. A technology ‘graduates’ the program when FDA attains sufficient confidence and familiarity with it. An example of a graduated technology is continuous direct compression, a pharmaceutical process that dispenses materials, mixes them, and compresses the blend to form tablets using equipment that is integrated — meaning there are no breaks in the process. Owing to the efforts of the ETP, applications that include continuous direct compression are now handled by standard CDER assessment processes.

Through the ETP, CDER has observed the rapid development of advanced manufacturing technologies across drugs it regulates. Recently, CDER established a Framework for Regulatory Advanced Manufacturing Evaluation (FRAME) initiative to prepare a regulatory framework to support the adoption of advanced manufacturing technologies that could bring benefits to patients. As manufacturing practices expand to embrace new technologies and scientific opportunities, policy initiatives must similarly grow to anticipate the complexities and, above all, protect patient safety and public health.

A global regulatory perspective on quality

The dominant trend in pharmaceutical manufacturing over the past two decades has undoubtedly been globalization. Over three-quarters of active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturing facilities are now located outside of the U.S. and many product launches are global events. But the COVID-19 public health emergency displayed the limitations of tangled international supply chains. With increased globalization, FDA’s oversight of the global pharmaceutical industry has stressed regulatory strategies that are data-driven and risk-based.

Some of these strategies relate to the challenges of making post approval changes in a global regulatory environment. International regula- tors have made great progress in facilitating efficient post approval changes; for example, there is now an international guideline on pharmaceutical product life cycle management. In addition to releasing guidance documents that convey FDA’s thinking, OPQ continues to work closely with international regulators to develop international quality guidelines for harmonized international standards. International guidelines in development have related to, for example, viral safety, continuous manufacturing, quality risk management and analytical procedure development.

CDER will continue leading international efforts to develop harmonized pharmaceutical standards. Yet the alignment of regulatory practices lies a step beyond harmonized standards. The future could well hold harmonized international submissions and inspections with open information flow between regulators, enabling the most pragmatic and efficient regulatory oversight possible.

The next 20 years

A retrospective look at the last 20 years of pharmaceutical quality regulation begets a prospective look at the next two decades. What might the future hold? One of the biggest opportunities and concomitant challenges relates to ‘big data’ and the impending explosion of data available related to drug manufacturing. The most sophisticated manufacturers are already using these data and adopting Industry 4.0 principles that integrate connectivity, artificial intelligence and robotics to enable systems that operate with little to no human involvement. Of course, not all manufacturers are striving for this Industry 4.0 paradigm. Regulators will likely face the challenge of overseeing an industry of old and new technology paradigms existing simultaneously. This may require a regular examination of the regulatory framework, including CGMP requirements being applied to manufacturing technologies that did not exist when the framework was written. If a new paradigm is realized, the future could well deliver unprecedented control, connectivity and digitization of drug supply chains with only minimal, pragmatic regulatory oversight.

The global nature of drug manufacturing justifies a highly coordinated international regulatory strategy. Imagine, for example, a ‘regulatory cloud’ where sponsors could provide one application for all regulators to assess in parallel. A regulatory future could include harmonized regulatory expectations for data elements and standards, regulatory assessments, inspections and a virtual repository for life cycle management of submissions. This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. In fact, the FDA is part of the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities that is piloting programs on collaborative international assessments and hybrid inspections right now.

There is still a long way to go to realize this regulatory and technology panacea. It is good when manufacturers identify an issue and remove a problematic product from the market; but consider that drug manufacturers recalled nearly 800 products last year. More robust manufacturing technologies and quality systems could better prevent some of these problems from occurring in the first place. Facilities still struggle with CGMP issues, and health systems and patients still regularly grapple with drug shortages.

One thing is almost certain: Regulators or industry will not be able to solve these problems by working separately. The global dimensions of pharmaceutical manufacturing and scientific innovation dictate a highly collaborative, data-driven and science-based path forward.