It’s no secret the generic pharmaceutical industry is in a time of change and dramatic growth. The patent cliff, a major driver of this growth with its crescendo in 2012, opened the door to renewed investment into new high-potential generic drug revenue streams. Since Hatch-Waxman in 1984, generic drugs have generated hundreds of billions in savings for U.S. citizens; becoming a timely governor that has helped slow rising healthcare costs. It’s equally apparent that the industry’s prominence and global supply chain has brought with it the scrutiny formerly reserved for Branded Pharma. Generic Pharma has become a global powerhouse. But with great power comes great responsibility, and it’s time for Generic Pharma to demonstrate its leadership on a number of fronts, including quality, safety and accessibility, as well as compliance and issues that have a far-reaching and long-term impact on the industry.

In a recent report “Global Markets for Generic Drugs,” analysts at BCC Research note: “The demand for generics is increasing steadily because of pressure to control health care costs. At the same time, fierce price competition in this area has put some companies in difficulties because of slashed profit margins.” Price pressures continue to eat into current and potential profit margins, and that has led to increased merger and acquisition activity in the sector as well, say BCC analysts.

The numbers associated with Generic Pharma are impressive. According to Ralph G. Neas, president & CEO of the Generic Pharmaceutical Association (GPhA), “Generic utilization hit an all-time high as 84% of prescriptions dispensed are now generic.” In 2012 the global generics sector, says BCC’s report, reached $269.8 billion, and is expected to reach $300.9 billion in 2013; and by 2018, some $518.5 billion via CAGR of 11.5%. According to GPhA, generics saved the U.S. health system $217 billion in 2012 and $1.2 trillion in the most recent decade. Not too shabby Generic Pharma!

With a market like that, Branded and Generic pharma are wrestling even more vigorously over patent rights in pursuit of capturing or preserving the profits from the most promising off-patent compounds — a trend that is showing no sign of abating anytime soon. Such market potential is attracting non-traditional responses as Branded Pharma (“originators” in analyst vernacular) is seeking to sell its own “branded” generics. BCC points to the rise of “Supergenerics” as another response to heightened competition and price pressure. Supergenerics, says BCC, are “offering added value as well as low prices.” BCC notes that many traditional generics companies are not positioned well to exploit the trend, but several majors are exploring their potential to create new revenue streams.

HEADWINDS

The expansion of the global generic drug industry has not come without its share of challenges. The regulatory community, it appears, has been especially challenged by the sectors’ growth over the last 30 years. It became apparent to many in the industry that the FDA and its Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) did not possess the resources to manage the tremendous influx of Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) as a growing number of branded pharmaceuticals lost patent protections.

In his GPhA annual meeting keynote, newly elected GPhA chairman Craig Wheeler remarked that “the companies represented in this room supply about 85% of every prescription drug in the U.S. healthcare system.” Just in the last decade, he said, the industry had saved $1.2 trillion because of the generic drug industry. “We’re a critical part of the solution, not a part of the problem of the health care system we’re facing in this country. Yet as an industry, we have never faced stronger headwinds to the vitality of our companies.” Wheeler pointed to the problem of delayed ANDA approvals directly: “We face cruel delays that wreak havoc on our P&Ls,” he said poignantly. Later in his talk he circled back noting that it’s high time the industry manage past the issue: “Although we are providing the major funding for the FDA in the form of user fees, we have not yet seen … progress in the shortening of regulatory timelines. The FDA has been hard at work preparing … it is only this year that metrics start to kick in. We collectively have a lot of work ahead to get this backlog reduced and achieve the timelines envisioned [by] GDUFA.”

According to Lachman Consultant’s Bob Pollock, the OGD received a record 1,059 ANDAs during Calendar Year 2012. In addition, OGD received 163 ANDAs in December, “traditionally a month with the most number of submissions, as firms attempt[ed] to beat the end of year clock,” said Pollock, on his company’s website. Another blockbuster month in 2012 was September, said Lachman, as the rush to beat the implementation of Generic Drug User Fee Act (GDUFA) occurred.

The ANDA backlog hit its zenith in August 2012 with 2866 ANDAs (plus 1,868 PAS Supplements) waiting processing. To remedy the resource issue, the FDA promulgated and passed into law GDUFA on July 9, 2012. According to FDA, “GDUFA is designed to speed access to safe and effective generic drugs to the public and reduce costs to industry.” Now the industry pays user fees to supplement the Agency’s costs of reviewing generic drug applications and the subsequent inspection of facilities. These additional resources will enable, says the FDA, to reduce a current backlog of pending drug applications, cut the average time required to review them for safety and increase risk-based inspections.

GDUFA: YEAR ONE

In her keynote address at GPhA’s February 2014 annual meeting, OGD acting director Dr. Kathleen Uhl took the opportunity to update attendees on GDUFA and agency’s activity implementing and administrating the Agency’s generic drug program. First, she offered GDUFAs’ three basic tenants: “Safety, so that there [are] high quality standards for generic products; Transparency, which gets to facility identification and communication, and … Access, such that there is predictability and timeliness in the review process.”

Uhl explained that GDUFA basically changed the entire spectrum of the generic drug review process and the interaction between the Agency and the industry, and ultimately, puts tremendous responsibility on everyone. “It increases our responsibilities, our obligations, our commitments and also accountability — not just to each other, but to the American people.”

Uhl said GDUFA obviously causes substantial changes in the review process and communications both internal and external, and changes related to inspection and inspection parity. “GDUFA actually,” said Uhl, “… really forces us to define ‘What is the Generic Drug Program?” She noted to GPhA attendees that many people understood that the OGD is the FDA’s generic drug program, but that in reality that is not the case: “It is not just OGD,” said Uhl, “It is essentially every single component of CDER, as well as other Centers, such as devices, and potentially even biologics.” Regardless OGD is at the center of it all, she said, because it serves as the interface for industry applicants.

Uhl, addressing the audience frankly said, “Now we realize that you … have huge expectations. You’ve paid your money. You want services. We get it. We hear you and we are working very hard … [to provide service] … and that right now [the FDA is] really about instituting the appropriate operations that we need to meet … very aggressive metrics and the implementation of this program, and the success of this program really requires substantial changes at the FDA.”

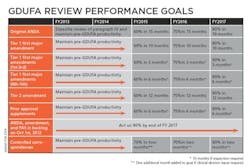

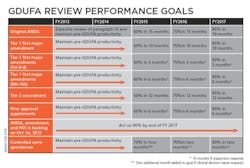

Uhl characterized the Agency’s performance goals as a “Five-year program that is sequential and with progressive implementation.” The bottom line is that by 2017 the FDA’s OGD is obligating itself to approve ANDAs submitted electronically within 10 months. “Because that is our goal,” said Uhl, and “you will get action … [and] get an approval, tentative approval or a complete response — that’s the metric that we are headed for in year five.” Of particular note in her slide “GDUFA Review performance goals” is the FDA’s commitment to act on 90% of backlogged ANDA, amendment and PAS by the end of FY 2017.

|

ANDA and Type II DMF Regulatory Science Inspections Systems and Electronic Standards |

In the name of efficiency (which is the point of FDA’s OGD reform after all), Uhl talked to a slide that outlined four primary categories of enhancements: ANDA and Type II DMF, Regulatory Science, Inspections and Systems and Electronic Standards. Within each of these categories the FDA proposes some very common sense means to increase the efficiency of the approval process, the issuance of complete response letters and the prioritization of inspections, tying them to ANDAs that are otherwise approvable or eligible for tentative approval.

Perhaps most vital to the FDA’s operational and structural efficiency actions is its proposed enhancements to IT systems and technology. This aspect of the FDA’s ANDA process improvement program includes the implementation of an “Integrated Regulatory Review Platform.” According to Uhl, it will provide great value to the OGD with its ability to measure progress against goal dates, real-time visibility into queue and status of applications and reviews, end-to-end support of the generic drug application review process, the reduction of manual and or duplicate entry and provide Agency access to searchable data and dynamic reporting as well as visibility when it comes to patent and exclusivity status, site inspection history and standardized communications documents. In other words, welcome to the modern world of IT functionality FDA!

Similarly, the IT enhancements program provides value to the industry as well, by improving planning and more accurate forecasting, consistent data and communications, structured reporting tools, the integration of process and technology and in general “Greater predictability and transparency of the generic drug review process.” Can we get an “Amen” for that Generic Pharma?

VICTIMS of SUCCESS

The GPhA’s keynote session included a panel discussion moderated by Marcie McClintic Coates, vice president and head of global regulatory affairs for Mylan. Among her panelists was Kate Beardsley, formerly U.S. regulatory counsel and someone who was on the ground floor of Hatch-Waxman. To kick off the discussion, Coates asked panelists if they recognized a link between Hatch-Waxman and GDUFA. Beardsley responded first. “It seems to me that GDUFA is in many ways … a culmination of Hatch-Waxman. Hatch-Waxman has been one of the most successful statutes … We have a huge and vibrant generic drug industry, we’re saving money for patients; everything that it was intended to do it has done and more.”

LABELING

At the absolute top of GPhA’s priorities is its mission to protect patient safety and access to affordable medicines. One of the biggest threats to these guiding principles, says GPhA, is the FDA’s proposed rule on prescription drug labeling. Unequivocally, GPhA opposes the proposed rule because it undermines the essential “sameness” of the label between generic and brand drugs mandated by law. According to GPhA president and CEO Neas, it is difficult to overstate the confusion that would be created among health care professionals and consumers if multiple versions of critical safety labeling information were to make their way into the marketplace.

Neas says GPhA is working with stakeholders and policy makers to ensure that the FDA’s proposed rule reflects sound policy, not politics. Given the present administration’s track record on creating policy that specifically supports its political agenda, chances are good this is going to be a tough row to hoe for GPhA and the industry. In his keynote remarks, Neas noted that in its rule making the Agency explicitly stated that the Mensing decision alters the incentive for generic drug manufacturers to comply with current requirements to conduct robust post-marketing surveillance evaluation and reporting and ensure that the labeling for the drugs is accurate and up-to-date. “With all due respect to the FDA and the Obama administration,” said Neas, “that is simply false, and frankly they know better.” Neas explained to attendees that it is not merely regulatory obligations that drive member’s compliance with current law: “Rather it is their design to provide clear, meaningful and up-to-date information about their products to patients and health care providers.”

Neas reminded attendees, including regulators in the room, that generic companies proactively participate with the FDA in ensuring the timeliness, accuracy and completeness of drug safety labeling in concurrence with regulatory requirements. “Sadly,” said Neas, “the FDA’s proposal, by opening the door to different labeling to be placed on prescription drugs, would create the very confusion it has sought to avoid for the past 30 years.” He noted that among consumers and patients, pharmacists and providers, the confusion would endanger patient safety. “Let me repeat that,” said Neas emphatically, “this confusion would endanger patient safety. Additionally, neither the FDA nor the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), conducted a cost/benefit analysis as the PMB is required to do.”

Economist Alex Brill of Matrix Global Advisors was commissioned by GPhA to investigate the economic impact of the proposed rule with regard to liability exposure and Mensing on the cost impact on public and private generic drug spending, should the rule become law. “His analysis shows that the proposed rule,” said Neas, “could increase spending on generic drugs by a staggering $4.1 billion per year. Of this, government health programs would take $1.5 billion and private health insurance would cover $2.6 billion.”

Neas and the GPhA maintain that the proposed rule adoption could result in fewer generic drugs coming to market, the withdrawal of manufacturers from certain markets, drug shortages and the under-adoption of affordable generic medicines and, ultimately, increased spending on drugs. “All of this,” said Neas, “is antithetical to the basic purposes of Hatch-Waxman. Moreover, it could raise costs for general therapies at a time when this country is focused on the need to further expand the accessibility of health care and reduce its accelerating costs.

According to GPhA, the industry group plans, in concert with its partners and other concerned groups (including former FDA officials said Neas) to take its case directly to regulators in its formal comments to the proposed rule.

THIRTY YEARS AND BEYOND

Few can argue that Generic Pharma won’t continue to play a prominent, leading role in the pharmaceutical drug industry. The advent of Hatch-Waxman has changed the pharmaceutical landscape forever — and in a good way. Certainly there are some less than positive aspects of the industry coming to light, especially those manufacturing in countries where the true culture of the industry, i.e., patient safety, is seemingly subordinate to profit motive. But there is no call, nor a need to indict the industry as a whole. Such bad actors are being called on to the carpet and singled out to atone for their sins, while others may soon be as regulators step up their scrutiny. In the meantime, it’s high time Generic Pharma exercise the leadership it has worked so hard to earn.