One could say that the desire to find consensus among diverse groups is built into the framework of Switzerland.

The Swiss Confederation is comprised of 26 member states, called cantons, which can vary significantly in geography, culture and even language (the country has four national languages). Prior to the establishment of the Swiss federal state in 1848, cantons existed as fully sovereign states, with their own armies, border controls and currencies.

The quest for consensus between different groups is further facilitated by Switzerland’s unique political system. The Swiss executive body is composed of seven Federal Council members from different political parties, all with the same rights and powers. Referred to as a concordance system, decisions are made through negotiation and compromise.

This mindset has also permeated the country’s pharma industry. The Swiss pharma industry is harmonized across the entire value chain, with robust representation in active pharmaceutical ingredients, clinical research, drug development, manufacturing and contract services.

With a population less than the city of London, Switzerland is known for consistently “punching above its weight class,” with its multifarious, well-networked pharma industry. The industry is considered a pillar of the Swiss economy, accounting for 5.4% of the country’s gross domestic product and over 40% of Swiss exports.

Much of this success, according to Michael Altorfer, CEO of the Swiss Biotech Association — a non-profit, member-driven organization representing the Swiss biotech industry — can be attributed to the stability and balance that has been built into the infrastructure of the industry over the course of its long history.

“Switzerland is so broadly and strongly established that there is no field where you would not find activity. There has been decades-long investment into infrastructure on all levels, from education to research development, to hospitals, to manufacturing capacity,” Altorfer says. “The attitude of Switzerland is really reflected in the pharma industry.”

But for the past three decades, a key piece of this well-oiled Swiss pharma machine has been R&D startups and biotech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which have thrived in the Swiss international collaboration model. Now, as countries around the world push for more nationalized approaches to supply chains, the Swiss pharma industry’s major source of innovation could come under fire.

The Swiss appeal

“Switzerland offers a stable and attractive tax environment for companies, and has a business-friendly regulatory climate,” says Sirpa Tsimal, director of investment promotion at Swiss Global Enterprise, the federal government body focused on external trade promotion.

“But the main driver — why international pharma companies are setting up shop in Switzerland — is the specialized life sciences know-how and the high quality talent pool they find here,” she says.

The talent pool is being filled from both internal and external sources. The Swiss education system offers traditional universities as well as universities of applied sciences. The latter focus on practice- and application-oriented degree programs. Additionally, Switzerland is one of the most popular expat destinations in the world and roughly one quarter of the country’s workforce talent comes from abroad.

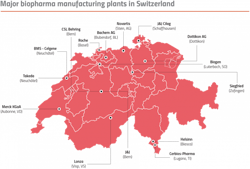

It’s no surprise that Switzerland has won the hearts of world-leading pharma companies such as Novartis, Roche and Lonza Group, who all call Switzerland home. Foreign heavy-hitters, including Merck KGaA, Celgene (Bristol Myers Squibb), Biogen, CSL Behring and Takeda have substantial — and growing — manufacturing footprints in the country.

Merck KGaA, which has had a presence in Switzerland for almost a century, now operates eight Swiss sites, five of which are manufacturing facilities. Over the past two years, the drugmaker has invested close to $500 million in new production capacity in Switzerland.

Importantly, the Swiss pharma industry isn’t limited to industry titans — in fact, a large portion of the country’s 250 pharma companies are SMEs — and it’s these types of companies that Altorfer feels are driving the industry forward.

“At Swiss Biotech, we represent the SMEs and the startups, which, over the last 20-30 years really have become the predominant force for innovation,” says Altorfer.

Many innovative projects started by small companies end up being acquired or licensed — and ultimately commercialized — by multinational pharma companies.

“Today, around two-thirds to three-quarters of new products launched in pharma began in SMEs and startups,” says Altorfer.

The overall startup scene in Switzerland is vibrant and biotech is leading the charge. According to the 2021 Swiss Venture Capital Report, the biotech startup sector grew by over 31% in 2020.

What’s more impressive, according to Altorfer, is that the sector has done this largely without cash infusions from the Swiss government.

“The Swiss government is very cautious in providing funding and doesn’t like to invest directly into biotech companies,” says Altorfer. “There is very strong support from the government when it comes to public/private partnerships, for example collaborations between private biotech companies and academic research organizations, but in cases like that, the funding goes to the academic research partner.”

To fill the void, philanthropic foundations such as Lausanne-based Venture Kick, have been established to help companies get off the ground through operational and financial support.

“This has enabled Switzerland to build a very effective biotech startup environment,” says Altorfer.

According to Tsimal, being small and diverse works to Switzerland’s advantage.

“Having corporate leaders, entrepreneurs and researchers in various disciplines so close together is a breeding ground for new ideas that make it fast to market,” she says.

Growth amid the pandemic

Although Switzerland did not commercialize any homegrown vaccines, the country played a significant role in the global pharma industry’s response, providing basic research, diagnostic solutions, treatments and much-needed contract manufacturing capacity.

In May 2020, Basel-based Lonza and Moderna announced a strategic collaboration to manufacture Moderna’s mRNA vaccine. To meet an ambitious annual goal of 300 million doses, Lonza spent $200 million building three vaccine production lines in Visp, an industrial center in the canton of Valais.

About three hours north, Novartis is busy helping to manufacture more than 50 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine at its Stein fill-finish facility. Earlier in the pandemic, the Basel-based drugmaker launched several trials aimed at repurposing existing drugs as COVID treatments.

And while the spotlight has definitely been on COVID-related projects, Altorfer says that Swiss biotech SMEs did not lose sight of their quest for innovation in other areas of unmet medical needs. Throughout 2020, they continued to invest heavily to expand R&D and manufacturing infrastructure, and to advance and broaden their portfolios of new drug candidates.

Growth for the collective pharma industry was a modest 2.8%, but according to an Ernst & Young analysis, 2020 was one of the strongest years ever for Swiss SME biotechs. The sector generated revenues nearing $5 billion, raised $3.75 billion in financing, increased R&D spending by 10%, and secured a record number of U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency approvals.

“If we look back at 2020, one may have thought that with the pandemic it would have been a year of struggle for the industry — but frankly in terms of biotech, we saw figures we’ve never seen before,” says Altorfer.

Rethink the reshore

Geography perfectly positions Switzerland to be a European pharma hub. And for an industry that thrives on exports — Swiss pharma exported over $100 billion in products in 2020 — open international networks are a must.

Since Switzerland is not a member of the EU or the European Economic Area, over 100 bilateral agreements are in place to secure European market access for Swiss pharmaceuticals.

When it comes to scientific discovery, the Swiss government has long pushed to make international collaboration a key part of its science strategy, offering grants and backing programs to that effect.

On the regulatory side, Switzerland and the EU have a mutual recognition agreement in place regarding GMP compliance — which means regulatory authorities in the EU and Switzerland’s drug regulator, Swissmedic, can rely on one another’s GMP facility inspections, waive batch testing when products cross borders, and share information on inspections and quality.

If ever there was time when industry collaboration was put to the test, it was the COVID-19 pandemic. The global pharma industry’s rapid achievements in treatments and vaccines would never have been possible without international scientific cooperation and coordination.

This need played directly to the strengths of the Swiss pharma industry, and even when borders were closed and lockdowns were rampant across Europe, the well-networked pharma industry was able to respond to the pandemic.

But now, with the worst (hopefully) behind us, Altorfer worries that the collaborative tide is shifting — and he’s concerned about the effect this could have on the innovative biotech sector.

“It is surprising to see that after this huge success of international collaboration, we find ourselves in a situation where there seems to be strong competition between countries. Various countries all seem to be working towards establishing their own supply chain, their own reserves, their own capacity,” he says. “It’s disappointing in the aftermath to see these nationalistic approaches where one is not willing to share with others. It seems we are drawing the wrong conclusions from what we have just experienced.”

This growing trend certainly contrasts with Switzerland’s approach of international collaboration.

“Switzerland is a small country. We depend on international collaboration. There is no question that for us the development of isolated R&D silos and national segmentation is not desired,” says Altorfer.

Future developments

Reshoring is not a new initiative — in fact it has already played out in Switzerland’s own antibiotics market. Antibiotics generally fetch low profits and face limited demands. As a result, research and investments dried up, and the production of antibiotics and ingredients shifted to lower-cost countries.

One proposed solution that could help stem the offshoring trend is the application of biotechnology to organic chemistry and production. Referred to as industrial biotechnology (IB) and considered a “green” technology, the process uses enzymes and microorganisms to produce products in many different markets, including small molecule APIs and intermediates. The goal is to improve chemical manufacturing performance and energy efficiency, which can ultimately translate into more cost-effective and sustainable small molecule drugs.

The IB field is nascent in Switzerland, but the Swiss Biotech Association and the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences (SATW) are looking to change that with the joint initiative, “Development of Swiss Biotechnology beyond the Biopharma Sector.” The initiative aims to support the formation of an IB cluster, connect stakeholders and identify ways in which Switzerland can contribute innovative solutions.

The hope is that Switzerland can build on the successes of a thriving biopharma sector — one that is ripe with achievements in advanced areas like monoclonal antibodies and cell therapies — and combine that with its ability to create innovative startups to establish a strong and connected IB sector.

The Swiss pharma industry’s collaborative approach has successfully driven global innovation in past decades and Altorfer predicts that the industry will continue to offer strength, experience and open attitudes going forward.

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'