How many years has the pharmaceutical industry been talking about supply chain fragility? Despite remarkable pharmacological and medical scientific advancements, the pharma supply chain’s robustness has not advanced meaningfully.

But opportunities arise from crises. It has never been more apparent than it is in this pandemic era that there are ways pharma companies and the industry can strengthen long-discussed supply chain vulnerabilities.

Although the industry has enjoyed many triumphs throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the supply chain’s weaknesses have also been on full display. This is a challenging era for drug manufacturers to tackle supply challenges, and yet this work’s importance can no longer be denied.

So what is meant by the desire for a “robust” pharmaceutical supply chain? For this discussion, a robust supply chain refers to manufacturers’ ability to maintain target fill rates and service levels and reliably deliver therapeutics to their customers (the next link in a product’s journey to patients) that are safe, efficacious, on-time and in the quantities demanded by the market.

For years, the pharma industry and individual manufacturers alike have professed the need to improve the supply chain, and yet little transformative progress has been made. If the pandemic has not taught all of us the critical nature of pharma supply chain transformation, nothing will. But in order to get there, there are steps individual companies can take as well as considerations the industry as a whole must make together.

It’s not all COVID’s fault

The good news is that, despite shutdowns around the world, strained geopolitical relationships, and transportation challenges during the early months of the pandemic, some portions of the pharma supply chain held up better than many feared at the onset of the pandemic.

Although retrospective reviews will be required to assess the era accurately, the supply of starting materials, APIs, intermediates, and excipients for small molecule drugs seems to have held up reasonably well.

According to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), shortages spiked in the first quarter of 2020 as the gravity of the pandemic’s risk solidified and hospitals across the country stocked up in preparation. Drugs related to ventilating patients — analgesics, sedatives and paralytics — increased in demand sharply. Unquestionably, there were localized supply strains as the pandemic settled into different areas of the country at different times. There are lessons to be learned here, given that there were plenty of situations in which there was ample or even excessive product in one market, but exceptionally low supply levels in other markets.

Ultimately, the supply chain for the manufacture of small molecule drugs must improve; the drug shortage levels in any given year are much too high. These shortages risk patient health and cost the health care system hundreds of millions of dollars annually; yet the sector weathered the pandemic better than anticipated.

The formal tracking of drug shortages began in 2001. Over the last 20 years, the criticality of the drug shortage problem has ebbed and flowed, peaking in 2011 with 267 drugs in shortage. Despite lower numbers of drug shortages in recent years, unacceptably high shortage levels in key therapeutic areas, such as oncology, antivirals, antibiotics, pain relief, and numerous other areas, persist.

Drug shortages can and do occur for innovator drugs under patent protection; however, these shortages are less frequent than generic drug shortages. When innovator drug shortages do occur, they are typically caused by incidents such as natural disasters or other “black swan” events, severe and specific problems with raw material supply, or critical operational breaches within a manufacturing plant.

Generic drug shortages are more pervasive and occur for numerous less obvious reasons, including manufacturers’ exits from specific markets due to low profit margins; quality problems among API, intermediate, and excipient suppliers; quality problems within manufacturers’ operations; industry mergers; unforeseen disasters; and regulatory hurdles.

But as the COVID-19 pandemic surpasses the official one-year mark, a natural impulse might be to dismiss the supply chain pressures within the industry as solely COVID-related — or reactions to a once-in-a-lifetime event that must be endured.

However, while the small molecule drug sector seems to have fared well during the pandemic, quite a different scenario developed within the biopharma sector and, to a reasonable degree, small molecule aseptic products. The supply chain for cell culture media, buffers, single-use bioprocessing system components, aseptic fill-finish and related areas was pressured before the pandemic. Then, as Operation Warp Speed gained momentum and commercial vaccine production accelerated, points within the supply chain for many manufacturers became quite problematic.

While urgently working to manufacture vaccines for the largest vaccination effort the world has ever seen, the biopharma industry is struggling to manufacture a multitude of required therapeutics within the context of an already strained supply chain. Operation Warp Speed may prove to be quite successful, but what about all the biologics for other life-threatening conditions?

How pharma can strengthen supply chains

De-risk the forecasts used to run manufacturing operations — Forecasts are always wrong

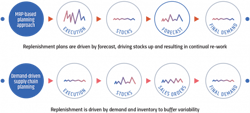

Today, nearly all pharma manufacturers run their organization’s operations on materials requirement planning–based systems. Enterprise resource planning systems use materials requirement planning (MRP) to link all the other financial and operational aspects of the company’s supply chain. The problem is that MRP-based systems require order volumes to function. Given that manufacturers lack concrete order knowledge, forecasts are used as the fuel to drive operations. Unfortunately, forecasts are always wrong, and MRP consumes them as if they were correct.

Stop focusing on investments in forecast improvement

Many pharma manufacturing supply chain professionals believe that the next technology step-change or more robust data will deliver needed forecast accuracy. They think that artificial intelligence and machine learning coupled with richer data will do the trick. Although these technologies are nice to have and are important, the most sophisticated assembly of forecasting technology and expertise in the world — the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) — tells a different story.

NOAA utilizes more than 100 years of historical data, supercomputers, AI, satellites — incredibly sophisticated technology tools and wildly talented analytical and scientific minds. Still, beyond 10 days, their forecasts are only 50 percent accurate. If this is the best NOAA can do with all the resources at its disposal, how can a pharma manufacturer possibly run its operations effectively based on forecasts?

Forecasting certainly has its place — revenue, trend and longer-term operational forecasts, for example. But manufacturers will never be able to improve their supply chains by running day-to-day operations based on forecasts.

Embrace demand-driven material requirements planning

For organizations using MRP push-based planning (virtually all pharma manufacturers), there is no coherent tactical plan for running the supply chain. Planners know the forecast data driving replenishment is incorrect, and they intervene daily, but their systems put them in a chronically reactive posture. They manufacture more when they see they will run short and stop production until the stock sells down when there is an excess. The result is a perpetual state of imbalance, leading to holding way too much of some inventory in some markets while experiencing shortages in others.

Even worse, the lack of a stable plan hides real supply chain cost drivers, resulting in less-than-optimal decision-making. The only lever to reduce costs, especially for generic drugs, is the unit cost. Manufacturers pursue the reduction in unit costs, often outsourcing all or certain key aspects of production to low-cost global markets. As a result, pharma supply chains have become extremely global, longer and more rigid — and the problem is getting bigger, not smaller. Unit cost may have come down, but agility, competitive advantage and total cost have all affected it negatively. This is not even to mention the dire ramifications of disruptions at any point in the supply chain for any reason.

Demand-driven planning resets the supply chain and addresses the root cause of planning failure by de-coupling the supply chain.

Execute a demand-driven operational approach

Effective demand-driven material requirements planning (DDMRPII) execution requires the right technology tools — specifically, tools built on a market service strategy foundation accepting that operations must be linked to a pull-based supply chain methodology. In a properly designed system, variability in demand is both accepted and understood. Supply chain setup decisions are based on capacity and segmented market strategies, entirely rooted in the manufacturer’s operational capabilities. It is quite simple: In a push-based approach, you are forced to match demand to your available supply, whereas in a pull-based approach, you match supply to your demand, which is fundamental for achieving target fill rates and service levels that ideally approach 100 percent.

DDMRPII approaches combine long-term strategic direction, market need and operational capacity. Marrying these factors with many tactical inputs such as product segmentation policies, material and plant capacity, resource planning, operational parameters, inventory buffer distribution and service-level policies generates a tactical plan tailored to accomplish defined business objectives.

Secure multiple sources of supply

Pharma manufacturers know that a lack of redundancy in the supply chain is problematic, but few have addressed the problem. Too often, pharma manufacturers continue to rely heavily on a limited number of suppliers — in many cases, a single source of supply. Although securing and validating multiple sources of materials and components supply is sometimes easier said than done, it must become a priority. Often, manufacturers will need to partner with global regulatory bodies to make this objective a reality. However, with a thorough understanding of both materials’ and processes’ critical quality attributes, manufacturers can determine and efficiently validate multiple supply sources in partnership with regulatory bodies.

Internally harmonize production

Even within their own operations, multi-plant companies often do not harmonize materials, equipment and processes. Take a biopharma manufacturer, for example. Suppose one facility is running low on single-use bioreactors. In that case, it often cannot tap excess supply at another facility within the company—many times, the same processes or similar processes are validated in different facilities, using different materials and processes. Even within the same company, facilities often cannot collaborate within their own network to manage supply. In many areas, a strong argument can be made for industry-wide harmonization; however, to start, biopharma organizations could implement consistent systems across their plants which would facilitate more efficient materials supply management within their organization.

Working together

Although individual companies can and must play significant roles to strengthen the pharma supply chain, there are areas where the industry as a whole, including equipment suppliers, international regulatory bodies and governments, must collaborate.

Materials of production harmonization

We can again use single-use bioprocessing systems as the example for this discussion, but there are many other materials of production in the industry with similar dynamics. In the case of single-use bioprocessing systems, various manufacturers’ bags and components designed for the same purpose often cannot be used interchangeably because there are slight differences in port configurations and other characteristics.

Sometimes, differences within systems contribute to improved performance; other times, systems companies fabricate differences to lock in their customer base. It is easy to understand single-use suppliers’ business strategies, but when biopharma manufacturers cannot tap other sources of supply, if individual manufacturers fall short, patients are ultimately put in an extremely vulnerable position. More consistency across the single-use market, and between systems companies in general, would enable pharma manufacturers to alter course if supply problems arise.

Regulatory harmonization

Heading into the pandemic, many pharma manufacturers had well-thought-out risk mitigation plans that included multiple sources of supply. However, in some cases, sources of supply that had been geographically distributed with considerable forethought were shut down simultaneously. For instance, a primary supplier in India, coupled with a secondary supplier in Italy, might seem like a well-crafted plan. A “black swan” event that shuts down many markets at the same time cannot be predicted and explicitly planned for. But, during an emergency, regulatory harmonization would allow processes to be moved worldwide much more quickly.

Reconsider generic drug market constructs

Generic drugs are critically important for keeping health care system costs under control; however, all stakeholders (including patients) have an interest in making sure generic drug manufacturers can manufacture safe drugs profitably. Payer-originated downward pricing pressures can inspire innovation and greater efficiencies — to a point. But a system that causes manufacturers to exit the market and essentially encourages dependency on substandard materials and manufacturers must be reconsidered.

Effective public–private partnerships

The pandemic has reminded us of the critical roles both the government and industry have in contributing to patient health. While the precise contours of new approaches to public–private partnerships require ample discussion, the need for ongoing communication and revised approaches is apparent.

Getting to work

From a pharma industry supply chain perspective, the pandemic era has been stressful and has further revealed and exasperated known vulnerabilities. Many of the weaknesses discussed at industry conferences and in board rooms for years were on full display in a potentially catastrophic context. For the industry and the nation, the idea that the pharma supply chain has a realistic possibility of breaking, creating untold levels of devastation, moved from theory to a genuine possibility. Unfortunately, that possibility remains very real.

However, crisis breeds opportunity. Manufacturers might now be able to move away from their reliance on push-based MRP-driven operations and their costly and inefficient reliance on forecasts. Additional moves, including internal production harmonization efforts, could help considerably.

Work requiring cross-market collaboration and new public–private working relationships will take time but is equally important.

Despite these challenges, the great news is that many other industries have addressed and solved the challenges the pharma industry currently faces. Let us learn from successes in other markets and get to work.