Precious things are kept inside castles, locked up in fortresses, or protected by walls. Be it a king or damsel or an entire city, barriers are built to shield our most valuable assets.

For pharma, few things have been considered more precious than one of the most profitable drugs in the history of humankind.

AbbVie’s adalimumab, known to the world as Humira, is an immunosuppressive drug approved to treat many illnesses, including debilitating diseases such as rheuomatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Humira is a drug like no other — it’s ability to treat a vast array of indications has earned it the nickname the ‘swiss army knife’ of pharmaceuticals.1 Millions of patients have been treated with Humira worldwide, and it’s estimated that it will amass a revenue of $240 billion by 2024.2

But the world’s top-selling drug had humble beginnings as a mere phage system invented by the Cambridge Antibody Technology Group (CAT) in Cambridge, UK. The team, which included scientists from Knoll AG (later bought by BASF Pharma), used genetic engineering to create an artificial immune system that had the capacity to replicate human antibodies, working it out until they had a therapeutic product in their hands.

Four years later, BASF Pharma published the first positive results from a phase 1 clinical trial involving 140 patients with rheumatoid arthritis being treated with the drug candidate called D2E7 — and the rocket launched.

Seeing blockbuster potential in D2E7, Abbott Laboratories bought BASF’s pharma business for $6.9 billion in 2001, which included the drug candidate. Shortly after, D2E7 received its first Food and Drug Adminstration approval on December 31, 2002, and was introduced to the world as Humira. In 2013, Abbott split in two, and AbbVie — now the owner of Humira — was born.

The first phage display-derived antibody approved in the U.S., Humira rose straight into stardom — within its first year, it had been approved in 38 countries and prescribed to 50,000 patients.1

In adition to being a life-changing medicine, due to what some call ‘beautiful legal work,’ and others a sinister monopoly, Humira has remained unrivaled in the market since the drug’s conception. AbbVie protected the biologic with a web of patents for many indications, creating an intellectual property defense wall that no legal department could get through, extending the drug’s market exclusivity far beyond what was granted by the FDA.

In the U.S., a year’s supply of Humira costs around roughly $77,000 — and patients’ out-of-pocket costs vary greatly depending on insurance coverage. In the EU, adalimumab biosimilars have been available since 2018, and have taken over more than half of the market share, which has not only resulted in lower prices for patients switching to biosims but also has driven down prices for the branded drug. In the Netherlands, for example, the market entry of biosimilars triggered discounts of up to 89% on branded Humira.

Now, with competition scheduled to enter the U.S. market in early 2023 — and potentially 11 products lined up to compete with Humira3 — all eyes are on the adalimumab biosimilar charge, with many experts claiming that the future of biosimilars in the country will inevitably be shaped by the success or failure of these launches.

After years of battling through patent litigation, will these manufacturers have the fortitude to stand out in a soon-to-be saturated market?

A drug worth protecting

Adalimumab is a recombinant human IgG monoclonal antibody. Monoclonal antibodies — or single clones — are a type of antibody that targets a specific protein.

In the case of Humira, the mAbs specifically target the cytokine human tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which is implicated in generating inflammation as part of acute phase immune reactions. Since inflammation is behind many symptoms of autoimmune diseases, mAbs are powerful drugs.

Humira’s success is amplified by the drug’s ability to treat many autoimmune disorders, most of which require lifelong medication. Immune disorders are also very common, affecting more than 7% of the global population, with more than 23.5 million Americans being diagnosed each year. And that number is increasing.4

“Prescribers — mostly rheumatologists — suddenly had with Humira somewhat of a silver bullet. One medication that targets processes that occur across more than one disease,” explains Dr. Sarfaraz K. Niazi, adjunct professor of Biopharmaceutical Sciences at the College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois in Chicago. Niazi is also a patent law practitioner with more than 100 U.S. patents in the biotech field and has developed a biosimilar to Humira, as well as two other biosims that have FDA approval.

“Humira is a highly effective, powerful drug,” Niazi says, and the data agrees. According to results reported by AbbVie, nearly 20% of patients with autoimmune disorders can reach remission within four weeks of treatment.

With support from the science and healing potential of Humira, AbbVie did an incredible job building a money machine that fed itself. By investing in numerous clinical trials, Humira became the magic pen with which most autoimmune disorders could be treated, becoming a go-to for prescribers around the world.

In response to a drug pricing investigation by the House of Representatives, AbbVie reported investing a total of $5.19 billion in Humira R&D expenditures between 2009 and 2018 — approximately 4.2% of the company’s Humira worldwide net revenue over that period.5

The investment paid off, and today Humira accounts for almost two-thirds of the company’s revenue.

If the story had ended there, perhaps Humira would be looked at in a more heroic light. But in order to protect its favorite prize, AbbVie employed an expensive legal arsenal of resources to shield its technology from being replicated.

Building the patent wall

The FDA defines a biosimilar as a “highly similar” product with no clinically meaningful differences from an existing FDA-approved reference product. Manufacturers making biosimilars have to demonstrate that the product is not clinically different in terms of safety, purity or potency.

“A biosimilar is a receptor-binding drug that replicates the cell processes triggered by the reference product,” explains Niazi.

Enacted in 2010, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) created an abbreviated approval pathway for biosimilar biological products. The act also outlined a path for biologic drugs to seek interchangeable status, if the drugmaker could provide additional data proving that a biosimilar product could produce the same clinical results as the reference product in any patient, including a detailed comparison of the history, as well as similarities and differences between the two. Importantly, interchangeable products may be substituted for the reference product without the involvement of the prescriber, whereas this is not the case with all biosimilars.

Currently there are 37 FDA-approved biosimilars in the U.S., 22 of which are commercially available on the market — and only three have received interchangeable status.6

While the BPCIA — which was included in the Affordable Care Act — was helpful in terms of stimulating biosimilar approvals in the U.S., it did leave some loopholes.

Tahir Amin, co-executive director of the Initiative for Medicines Access and Knowledge (I-MAK), says that because these bills are built into larger legislative acts, it’s harder to crack them down and change them when necessary, such as in cases of patent misuse — of which critics, including Amin, have accused AbbVie.

“By drafting this legislation into large bills that might not be publicly associated with these issues, when you try to bring up changes to the BPCIA, people begin politicizing the legislation because it is part of the Affordable Care Act, making it difficult to extract that out,” says Amin.

Protecting the largest pharma empire of all time takes money and foresight, and must begin at the first patent filing, according to Amin, who practiced as an intellectual property attorney for 10 years in commercial law firms.

“The way that first patents are created informs how the subsequent ones are filed,” he says.

By carefully crafting the first patent, companies can set themselves up for intellectual property protection success for decades. If they purposely obfuscate details, they can file new patents with slight variations and extend patent exclusivity.

It’s a game of looking threatening, too. “These companies also focus on filing an excessive number of patents knowing that they might not need all of them but the sheer amount might scare drugmakers enough to keep them from developing their competitor product,” Amin says.

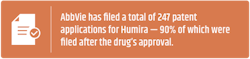

And it has been precisely this type of patent reputation that has kept AbbVie in the spotlight for the last few years. While the original patent expired in 2016, AbbVie has filed a total of 2477 patent applications for Humira — a portfolio it has aggressively used to knock down biosimilars challenging its market.

While most innovator companies insist vehemently that patents help protect innovation, Amin argues that FDA exclusivities provide enough market protection for companies to launch a product.

“Something that is not recognized or discussed enough is that when companies have a new biologic product, you get your BLA and receive 12 years of marketing exclusivity. So that is separate to any patent — nobody can come on the market for 12 years from the get-go,” says Amin.

Within that period, other drugmakers can submit applications for biosimilar approvals but can’t market them until the FDA exclusivity and any patent protection litigation is finalized.

The BPCIA mandates that biosimilar applicants disclose their FDA applications to the innovator companies within 20 days of filing that application. “And then the patent dance starts,” says Amin.

Niazi, on the other hand, believes that AbbVie’s construction of patents is “beautiful legal work.” He argues that while the first few patents filed for Humira covered many of the 14 worldwide and 10 U.S. indications it currently has, the company cleverly filed varieties, such as an auto-injectable pen or a stronger dose — that made all the difference.

“They [AbbVie] were smart to listen to patients’ requests once the product was live and make sure that their patent portfolio was reflecting the changes they were making in needle size, and such,” Niazi says. AbbVie also removed the citrate buffer that causes smarting pain; according to Niazi, it was known all along, but AbbVie let the patients suffer and made this change only when the patent expiry came near — a cruel strategic move.

AbbVie’s patent portfolios are aggressive indeed — when the drugmaker countersues companies attempting to bring a biosimilar to market, they litigate with as many patents as possible. “AbbVie’s patent thicketing strategy on Humira has become almost legendary, albeit for the wrong reasons, when people realize that none of these companies were able to litigate through them,” Amin says.

Patent litigation with generics is different from biosimilars due to the way that the drugs are developed in the first place. “Biologics are much more complex; they have way more patents because of the nature of the technology. There are many different ways to manufacture and develop it,” says Amin.

The result? An even thicker patent wall.

And protecting the wall comes at a hefty cost. According to patent litigation statistics, defending a patent can cost between $2 and $4 million per patent.

Brick by brick, the wall falls

Most of the arguments against AbbVie focus on the company’s misconduct and antitrust violations in connection with its aggressive enforcement of patents to prevent the sale of biosimilar versions of Humira in the U.S.

“It wasn’t just one case, with Humira, but actually all the litigations chipping away at this patent structure keeping the technology exclusive,” says Amin.

But the wall protecting Humira has started to fall, slowly but surely, brick by brick.

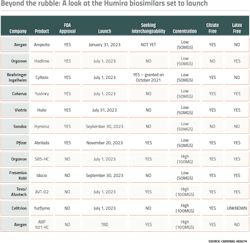

Leading with an impressive portfolio of biosimilars and a hefty legal department, the first to take on AbbVie was Amgen with Amjevita, which is lined up to be the first biosimilar to hit the market in January 2023.

Not long after the FDA accepted Amgen’s biosimilar application, AbbVie sued for patent infringement claiming that Amjevita infringed on 10 Humira patents and asked the court to block the launch if and when the FDA issued an approval.

“Intellectual property litigation is aggressive, and more often than not just intended to scare drugmakers with smaller legal teams away,” says Amin. AbbVie did precisely that, not only suing for the 10 patents but threatening to come after Amgen for 51 other patents as well.

While specific financial terms of the agreement were not disclosed at the time, the companies announced a settlement in September 2017, with AbbVie granting Amgen patent licenses for the use and sale of Amjevita worldwide on a country-by-country basis.

While each company making a biosimiliar argued similarly, it was Boehringer Ingelheim who sparked hope that perhaps a Humira copycat could launch before 2023, when they initially refused to settle and counterargued that AbbVie intentionally overlapped and added on patents.

“Boehringer came up with this novel argument saying that many of these patents were bad faith and that they would deliberately have this strategy from the start. And we thought actually, this is a pretty novel argument from a legal point of view,” says Amin.

Eventually, in May 2019, Boehringer agreed to settle and keep its product on the shelf until 2023.

While settlements and legal teams are expensive, defending the patents gives companies making the reference product control over competitive launches, allowing them to better prepare and forecast their financial future.

Also, reference-product companies can try to bargain with biosim drugmakers, who often sign away international markets when settling as they are focused on the U.S. rather than abroad. “Companies often decide to keep the U.S. one because the country’s market is much more valuable because there’s no negotiation, there’s no pricing control. They can charge whatever they like,” Amin says.

Alvotech, who is partnering with Teva Pharmaceuticals on the U.S. commercialization of its adalimumab candidate, has been the most recent one to settle, inking a deal with AbbVie in which the Iceland-based drugmaker agree to wait until July 2023 to launch its biosimilar. The companies had been in a lawsuit tug-o-war, with Alvotech accusing AbbVie of employing a “wrongful monopoly” on the drug and AbbVie later accusing Alvotech of recruiting one of its manufacturing execs to steal Humira trade secrets.

Climbing to the top

There are four main ways in which Humira biosims can set themselves apart from each other: dose concentration, interchangeable status, needle size, and a formula without latex or citrate.

Dose concentration matters because although both high-concentration and low-concentration versions of Humira are currently on the U.S. market, over 80% of prescriptions are for the high-concentration solution, providing an incentive for companies with a biosimilar that offers this option. None of the FDA approved biosims are offering high concentrations, but pending biosims, such as Organon’s SB5-HC, Teva and Alvotech’s AVT-02, Celltrion’s Yurflyma, and Amgen’s ABP 501 HC are all high concentration.

The second factor, interchangeable status, matters because it would allow pharmacists to replace Humira with a biosimilar without having to address the swap with providers. While there are only three interchangeable biosimilars on the U.S. market as a whole, two approved Humira biosimilars are seeking interchangeable status — Teva’s AVT-02 and Amgen’s second Humira biosim, ABP 501 HC.

Needle gauge makes a different in terms of patient comfort — the higher the gauge number, the smaller the needle. AbbVie initially designed Humira’s needle gauge to be a 27-gauge needle, later coming out with a 29-gauge needle. Most Humira biosims are offered in a larger-gauge needle with only Boehringer Ingelheim’s Cyltezo and Sandoz’s Hyrimoz’s needle sizes being 27-guage.

In adalimumab formulations, citrate and latex can both be used as excipients. Citrate, for example, acts as a buffer, helping the biologic retain its chemical and physical products. However, in Humira injections, it has been found to potentially cause pain, so drugmakers might be incentivized to remove it from the ingredient list. The only two biosims entering the market with citrate in their formulation are Organon’s Hadlima and Sandoz’s Hyrimoz — the rest are citrate-free.

With latex, the concerns have to do with allergies. While only less than 1% of the population is naturally allergic to latex, according to Mayo Clinic, repeated exposure to latex may increase sensitivity. In order to protect both employees and patients who might have a family history of allergy development, AbbVie and several of the biosims are offering latex-free formulations.

As to which drug will come on top, experts agree that to succeed in the biosimilar market you need timing, a lot of money, and legal teeth. “Biosimilars are not for the weak. The investment necessary to succeed in this market given the current regulatory expectations is massive,” Niazi says. “But you see that the drugmakers going after Humira are seasoned veterans.”

According to Niazi, due to the nature of patents, biosimilars, and trends seen in Europe, the drugmakers more likely to succeed are the ones who reach the market first. “Amgen is leading because in a way they were preparing for this by already having and working with a robust portfolio of biosimilars for years before going after the best-selling drug ever.”

Amgen is betting on this head start, says Gary Fanjiang, vice president and general manager of Biosimilars, at Amgen.

“We believe our five months head start on biosimilar competitors will support early adoption of Amjevita and are confident that our success in the EU will translate to the U.S. market,” says Fanjiang.

Amgen also has decades of experience — and Fanjiang says that will help set its biosim apart.

“We have over 40 years of experience manufacturing complex biologics and a history of reliable supply. We will also leverage our experience designing and delivering patient support programs for our innovator biologics to ensure patients receive the same level of support when starting Amjevita.”

And while patients will also see a reduced-price tag, a crowded biosim market on top of AbbVie’s settlements will mean that the change won’t be as drastic as it has been outside the U.S.

“It’s going to be a pretty saturated place in 2023. I don’t know how much the prices are going to come down because companies must still make a profit from their drug, and some of that money will go to AbbVie,” Amin says.

But despite the impressive number of roadblocks, biosimilars are still a highly profitable business opportunity for pharma. “Biologics offer a huge market in terms of the profit, numbers like nobody have seen before,” Amin says.

Biosimilars’ big moment

Despite it being a new market, the good news is that the industry has been through something similar — pun intended — before.

Although different in nature, biosim drugmakers can look at the introduction of generics as a rough guide of what disrupting a name brand market can be like.

Craig Burton, senior vice president of Policy and Strategic alliances for the Association for Accessible Medicines, and executive director of the Biosimilars Council compares the situation to the adoption of Prozac generics.

“When the first generic competitor to Prozac was made available to patients back in 2001, national newspapers and network television evening news programs ran stories about this milestone. Prozac was one of the most prescribed medicines, so this was truly big news; it was important for physicians and pharmacists and patients to know safe, effective and more affordable options were now available,” explains Burton.

This, combined with the years of good reputation that Humira has amassed should help.

“With competitors to Humira about to launch, biosimilars are about to have their big moment,” says Burton.