EVERY EMPIRE HAS ITS DAY, and the sun may already be starting to set on U.S. and European domination of the world’s pharmaceutical industry. More than half of the 185 global industry executives recently surveyed by PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC) (see "Bullish on Asia" box, below) agree that global pharma’s center of gravity is shifting to Asia. A growing number of multinational drug companies now plan to move more strategic operations to India, China, Singapore and other growing pharmaceutical hubs [1].

Click here to read Business Week's June 18, 2007 cover story, "The Real Cost of Offshoring."

What do YOU think about offshoring's affect on the pharma industry? Click here to take our poll.

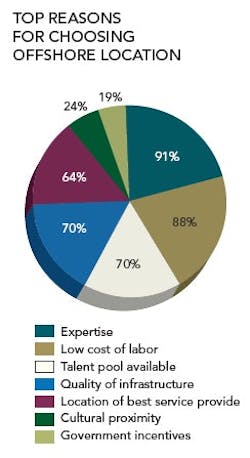

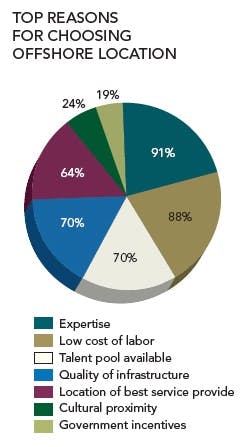

While cost savings may still be important in pharma offshoring and outsourcing strategies, speed and access to new workforces and markets are becoming equally critical. Last year, drug and healthcare companies cited “expertise” as their top reason for selecting an offshore location, according to “Next Generation Outsourcing: The Globalization of Innovation,” a 2006 Outsourcing Research Network (ORN) survey and study by Arie Lewin, professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and director of the University’s Center for International Business Education and Research.

The consulting firm, Booz Allen Hamilton, became involved in the annual study for the first time last year, says coauthor and Booz Allen Hamilton analyst Mahadeva (“Matt”) Mani. “Access to talent is becoming much more important,” Mani says. Comparing survey data from 2004 and 2006, he says, speed to market as an offshoring driver grew by nearly 70%, while cost savings inched up by 5% during that period.

ORN’s study takes a generally rosy view of offshoring and its impact on onshore jobs, suggesting that, at least when it applies to R&D, the practice has little impact on U.S. jobs and may even create more positions at home (see "Debunking Myths or Creating Them?" box, below) [2]. Pharma companies that have already outsourced like the practice because they’re seeing positive bottom-line results, Mani says.

Source: The Globalization of Innovation, p. 77.

For some, offshoring may offer an easier alternative to recruiting talent in the U.S., Mani suggests. “We’re starting to see a gap in the supply of M.S. and Ph.D.-level U.S. candidates in science and engineering,” he says. “For the past few years [before caps on these visas were reduced from 135,000 to 65,000 per year], H-1B visas have masked the problem.”

Last year, ORN and BAH interviewed 537 corporate executives for the study, Mani says, and several of them, across all industries, agreed that fewer qualified people are applying for new scientific and engineering positions. “It’s taking many companies from six to 10 months to find the right person, and important projects are taking longer as a result,” Mani says. “We may not be in a crisis right now, but if we continue down this road for too long, some may start to think it’s crazy to try to hire people for some positions in the U.S. when a supply is available elsewhere.”

Biotech feels the pinch

Although biotech may not exactly be booming right now, demand for talent is strong and some biotech companies, particularly in California, are already feeling the pinch. A senior scientist at one small biopharma manufacturer near San Francisco, who asked to remain anonymous, says that some new mid- and senior-level positions at his company have been unfilled for over six months. The Golden State looked into workforce issues across all industries last month, and concluded that the number of highly educated immigrants to California would have to more than double to meet projected needs. [3]

“Increasing the number of H-1B visa holders allowed to work in the U.S. is a good temporary fix, but the real solution is to create programs that continue to train the workforce,” says Joe Panetta, CEO of BIOCOM, a consortium of 550 leading biotech companies based in California. The organization has established a Life Sciences summer institute to allow students and teachers to work in the industry and experience “real-world” situations.

Is U.S. Pharma heading the way of U.S. IT?

But some fear that pharma and biopharma offshoring are already heading the way of IT and telecom in the U.S., and that the industry will offshore or increase reliance on foreign workers with H-1B visas, simply to avoid having to pay U.S. scientists and technical staff competitive salaries.

Although there’s no single, organized lobby for scientists and engineers, public concern has registered in Washington. In April, Senators Dick Durbin and Chuck Grassley introduced a bill designed to prevent exploitation of foreign workers and the loss of U.S. jobs. “Our immigration policy should seek to complement our U.S. workforce, not replace it,” Durbin said.

Blogger and former Dartmouth professor Geoff Davis, who now works for Microsoft Corp. and runs the Engineering Science blog on phds.org, has tracked NSF data and noted that the number of Ph.D.s awarded in the U.S. has been increasing since the mid-1990s. Indications are strong, he wrote last December, that the latest Ph.D.s may run into a tough job market. [4] In 2005, the U.S. graduated over 9,000 doctorates in life sciences fields.

An inconvenient truth?

Yet, many of these graduates may not have the skill sets that industry needs. “There are thousands of people languishing in low-paid post-doc positions, receiving $25-30K/year after more than 10 years of college and training, because biotech companies will not hire them,” wrote Dave Jenson, a recruiter from CareerTrax, Inc. on the career forum of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (www.aaas.org) last spring.

“There is actually an overage, rather than a shortage, of scientists in the U.S.,” he continued. “However, there is a shortage of people who have industry experience. This is due to the fact that biopharma companies do…nothing to help the glut of academically-trained scientists make the transition to industry. They cry and moan about the need to find good people, and they even work closely with junior colleges and community colleges to help programs that turn out low-level factory workers for their manufacturing plants.” [5]

Is the gap so wide between university science curricula and industry needs? “Too many U.S. graduate students in science are being trained to be, and given the expectation that they will be, independent researchers in an academic setting,” Davis wrote in April. [6]

The typical career track for many science degree holders in biotech is to gain experience at a small company, then move on to larger firms. As Lonza CEO Stefan Borgas told an audience at BIO 2007 in Boston last month, biotech companies need to start building talent from within, rather than pillaging from other manufacturers.

Addressing the needs of manufacturing, he suggested that academics are being overemphasized at the expense of training that would lead to a “skilled and vocationally trained workforce” (Article, p. 13). “We need more of an interdisciplinary focus, and more attention to the business side, not just the science, in training,” agrees BIOCOM CEO Panetta.

Is a U.S. pharma workforce crisis in the making? “If you believe industry, which is lobbying to increase the quota for H-1B visas, the problem is pretty serious,” says Fuqua’s Lewin.

Others disagree, among them Lewin’s colleague Vivek Wadhwa, a former tech industry CEO who is now executive-in-residence at Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering. “This shortage is a myth,” he says, and in engineering, the only deficits are being seen in civil engineering (coincidentally, the lowest paid of all engineering tracks in the U.S.). At the same time, he points out, U.S. engineering and science salaries have remained flat or decreased over the past 10 years.

Wadhwa is sympathetic to insiders who complain of post-doc slavery. “When you pay them $25,000/year stipends, you simply make it uneconomical for the brightest U.S. students to pursue graduate studies.”

Is industry contributing to the downfall of U.S. competitiveness? Absolutely not, Wadhwa answers. “CEOs are doing what’s best for their companies, and shareholders would fire them for doing otherwise, because dealing with social issues is not their job,” he says, “but rather, the job of the government.”

He suggests government labs such as NSF and NIH treble post-doc salaries so that they more closely approximate industry salaries. “Even if the cost of doing that amounted to $1 billion/year, that would be a small price to pay for ensuring and increasing the nation’s future competitiveness.”

Wadhwa already sees chilling portents. For example, nearly one-quarter of all U.S. patents are now being filed by foreign nationals on temporary visas. The comparable figure for U.S. citizens abroad doesn’t even come close. As for foreign holders of H-1B visas, Wadhwa suggests a modest proposal: Let them have green cards.

Whatever the solution, the U.S. should act quickly. “Competitiveness won’t improve while we pretend there are shortages,” he says.

China figures inflated

For anyone concerned about science education and skills shortages, few reports were more frightening than data published in 2005 comparing the 70,000 B.S. engineering degrees awarded in the U.S. with 600,000 in China and 350,000 in India (Pharmaceutical Manufacturing, November/December 2005, p. 9). Proposals called for increasing enrollments so that the U.S. would graduate 100,000 more U.S. engineers a year. This solution would only have led to a glut and lowered salaries further, as Wadhwa and his colleagues at Pratt and Duke’s Center on Globalization, Governance and Competitiveness (CGGC) learned.

The Chinese government’s efforts to discourage “elitism” caused science and engineering enrollments to increase by 140% between 2001 and 2006, they discovered. As a result, the skill sets and training of many graduates counted as “engineers” in Chinese statistics are not on par with those of U.S. graduates. Although comparable figures aren’t available for pure science degrees, for engineering, adjusted numbers show relative parity, with the U.S. producing 750 engineers and IT professionals per million citizens, compared with 500 in China and 220 in India. [7]

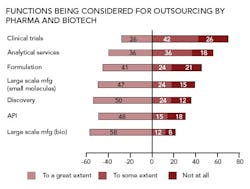

Source: Gearing Up for a Global Gravity Shift, p. 24

But looking at the number of science and engineering degrees being awarded in the U.S. will not tell the whole story, Lewin says, because more international students on visas, who make up 60% of U.S. engineering Ph.D. students [8], are returning home to start their careers. This situation started to change about seven years ago, as economies began to develop and more foreign governments began to offer incentives for students to return home, Lewin says.

What do you think about offshoring's affect on the pharma industry? Click here to take our poll. |

NSF has estimated that about half of all the foreign engineering and science doctorates in the U.S. return home soon after graduation. According to the Pratt/CGGC study, roughly 30% of all Chinese engineering Ph.D. students in the U.S. returned home in 2005. “Industry assumes that an increase in visas will address the problem, but underestimates the attraction of returning home, the draw of nationalism and the desire of people to work in their own countries,” Lewin says.

Even if one doesn’t believe there is a workforce shortage today, there are strong signs that one is coming, as two trends collide. In the U.S. and Western Europe, the workforce is aging (at least it is outside of the Scandinavian countries, where workforce entries and exits are in balance, Lewin says). “Even if the proportion of scientists and engineers remains the same in the overall labor mix, more people are retiring from than are entering the fields of science and engineering,” Lewin says. At the same time, fewer students are graduating from U.S. high schools with the math and science training required to study engineering and science in college.

There’s clearly a need to improve elementary and secondary education in the U.S. Yet, suggesting that U.S. education is inferior or is causing the outsourcing and offshoring trend would be oversimplifying. There are differences. For instance, in Asia, students are exposed to more complex scientific concepts much sooner than students in the U.S., Mani says. However, the Pratt/CGGC study found, the best U.S. science and engineering graduates are highly creative and more likely to challenge the status quo than their Asian counterparts, who, in turn, are more likely to trump U.S. grads with their work ethic. [8]

While the controversy over visas and immigration continues in the U.S., pharma’s staffing picture is changing every day. If skills gaps exist in the U.S., they are also developing in some hot spots in Asia, and top technical salaries are hitting record highs in cities such as Bangalore [9]. There’s no doubt that the hunt for talent will continue, both on and offshore, but as Lewin puts it, “Smart companies are thinking very hard about why they’d outsource, and where."

References

1. Gearing Up for a Global Gravity Shift – Growth, Risk and Learning in the Asia Pharmaceutical Market, PriceWaterhouseCoopers, May 2007.

2. Lewin, A., and Couto, V., Next Generation Offshoring: The Globalization of Innovation, Offshoring Research Network, Duke University Fuqua School of Business and Booz Allen Hamilton, March 2007 (link available on pharmamanufacturing.com).

3. Johnson, H. and Reed, D., Can California Import Enough College Graduates to Meet Workforce Needs? The Public Policy Institute of California, May 2007, p. 3.

4. Davis, G., “Watching a Train Wreck” December 2006, http://blog.phds.org/2006/12/13/watching-a-train-wreck-part-1).

5. Jenson, C., Career Forum, AAAS, April 2007.

6. Davis, G., "A Crisis is a Terrible Thing to Waste,” PHDS.org (blog), April 2007.

7. Gereffi, G., Wadhwa, V., et al, Framing the Engineering Outsourcing Debate: Placing the U.S. on a Level Playing Field with China and India, 2004 (available on pharmamanufacturing.com).

8. Wadhwa, V., Gereffi et al, “Where the Engineers Are,” Issues in Science and Technology, University of Texas, 2005.

9. Tucker, S. “A Bidding War Makes for Crazy Salaries Across Asia,” Financial Times Germany, May 18, 2007.

Bullish on Asia

Despite the risks of setting up operations offshore, most pharma executives are optimistic about offshoring in Asia, according to “Gearing Up For a Global Gravity Shift,” a PriceWaterhouseCoopers report published in May. A growing number have seen positive results from past efforts in the region and are dedicating more resources to set up joint ventures and other operations in Asia.

Survey results also suggest that cultural and other barriers proved to be less significant than offshoring companies had expected. However, there continue to be some concerns about intellectual property (IP) protection and about the potential for fraud, in illegal extensions of the connection-making that’s summed up in the terms Bakhsheesh or Quanxi. Such extensions moved China to sentence the former director of its FDA equivalent, the SFDA, to death last month.

Half of the respondents from global pharma companies view corporate fraud as a concern and 38% said corruption had led to difficulties in existing ventures in Asia. However, most respondents believe that their corporate policies can deal with the problem. IP protection was also noted as a concern, but 74% of respondents are optimistic or very optimistic that the IP environment will improve over the next five years.

Debunking Myths or Creating Them?

As offshoring of higher-skill jobs increases, fewer jobs are being eliminated onshore, according to "Next Generation Offshoring: The Globalization of Innovation." The Offshoring Research Network’s 2006 study, which surveyed 537 companies in the U.S. and Europe, also found that only 27% of respondents were not considering offshoring.

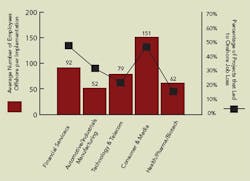

Since 2005, the percentage of offshore projects that resulted in the loss of jobs onshore has decreased by 48%, the survey says, and the number of jobs lost per offshore project has fallen by 70%. In general, pharma offshoring has resulted in less job loss than offshoring in other industries (Graph), and offshoring of R&D, in particular, is not expected to lead to a reduction of U.S. jobs, the study says.

Although onshore job loss was significant for offshoring of financial and back-office functions, 90% of all R&D offshore implementations did not lead to job losses onshore, the study says. However, the new innovation paradigm will require new ways of thinking. U.S. and European companies will need to better integrate globally dispersed teams of knowledge workers. Also, as offshore workers become responsible for higher skill functions, colleagues in the U.S. and Europe will have to learn how to better communicate, collaborate and compete with them.