It’s hard to find good help. That’s been a common refrain of employers since, well, maybe since Noah went ahead and built the ark all by himself.

It’s easy to understand this when unemployment rates are low—those who want to work can work, and employers have fewer qualified, motivated workers to choose from. But what about when jobs are scarce, as they are now in the U.S.? Is it still hard to find good help?

Unfortunately and paradoxically, yes. And this holds true within the manufacturing sector. Even though competent people are sometimes literally starving for work, manufacturers cannot always find people to fill open positions.

Incompatibility is a problem—people have skills, but just not the right ones. To some extent, community colleges and technical schools have dropped the ball, says Steve Sawin, president of Operon Resource Management, a firm which helps life sciences companies manage their workforces and “onboard” new employees.

There are exceptions, of course. Witness North Carolina’s Pharmaceutical Center in downtown Winston-Salem. The Center, a collaboration between local community colleges, partners with life sciences firms and government to monitor industry needs and trends, develop new (and often accelerated) courses based on demand, and help connect manufacturers who need “help” with professionals who can help.

But Sawin has a point. Community colleges, and undergrad and grad programs, are still struggling to align themselves with the drug industry’s present and future needs.

Manufacturers are not free from blame either, says Sawin. Many do a poor job of product and process training, especially prior to placement. They ask, “How do we make this resource ready to hit the production floor to make a contribution initially and to meet the expected learning period?” he says. “On the premise that quality and compliance can otherwise be maintained, it becomes a financial trade-off: learning curve attainment to idle labor cost.” Thanks to staff reductions, many managers and supervisors don’t have time to devote to mentoring and the oversight of training once workers are on the floor.

Another angle to the “good help” issue goes beyond training, however, Sawin says. It has to do with “employability.” An ambiguous term, but it relates not just to skills but to work ethic. Potential hires are just not all that enthused about the jobs they’re applying for and taking.

"What we're hearing from clients is that there are many candidates who simply lack a reasonably good attitude and work ethic," Sawin says. "That's troubling to me, because these are qualities that are developed in a home environment." In other words, work ethic is not something that can be taught or trained. (Or can it? I'd be open to hearing your ideas.)

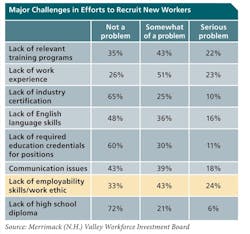

Sawin called my attention to a study that was recently conducted by New Hampshire's Merrimack Valley Workforce Investment Board (box), which polled manufacturers from various industries in that region about their challenges in recruiting new workers. The chart shows some of the results. While experience, language, and so on continue to be issues, employability and poor work ethic may be the biggest issues of all.

Each generation seems to say, "these kids today really don't get it." (After all, we are talking mostly about younger workers—the Facebook generation and those a bit older.) But as far as manufacturers' needs are concerned, is this now more true than ever?

Here’s another possibility: Some employers just don’t get it. They’re offering a salary, but little else. In a recent interview, Shire HGT’s Bill Ciambrone, senior VP for technical operations, reminded me that manufacturers, too, have an obligation.

“Most companies spend an awful lot of money on plant facilities,” he says. “I find it bizarre to not also invest in training, as if somehow you’re naturally going to get qualified employees off the street.”

“People are a key resource that we invest in,” Ciambrone says, “and it’s only good business to make sure that they’re adequately trained.”

So the next time someone tells you that it’s hard to find good help, nod politely in agreement. Then remind them that it’s also hard to find good work.