Author's Note: Listen here for an audio interview with Mary Cianni and Frank Giampietro of Towers Watson on what pharma has learned from past mergers and acquisitions.

Most of our biggest drug companies are what Mary Cianni, Global Practice Leader for M&A of the consulting firm Towers Watson, calls “serial acquirers,” who make a habit of snatching up smaller prey for sustenance. Drug pipelines are no longer developed but bought. Doddering big pharmas become burgeoning biotechs overnight through the magic of M&A. The serial acquirers must be forgiven for this—it’s in their business blood.

So it must be sheer hell out there for many of you, their past, present, or future employees. Conventional wisdom holds that whenever a company undergoes a merger or acquisition, employees suffer. First, there’s the emotional strain of whether or not you’re going to keep your job, or whether that job will irrevocably change for the worse—the new boss a tyrant, your workload doubling, your best work buddies shipped off to another site. Our worst fears come calling. Maybe you’ve already been told you’re out of a job, in which case you don’t want to hear about silver linings.

Sheer hell . . . or so I thought until talking with Cianni and colleague Frank Giampietro, a managing consultant, about studies Towers Watson has done of workers who have been through mergers and acquisitions. According to these studies, here is the drug industry’s general response to an M&A, in comparison with other industries: been there, done that.

A megamerger? A hostile buyout? A spinoff snatch-up? We’ve seen it before. There’s a “sense of resiliency” among pharma employees in regards to major upheaval, says Cianni. Workers tend to say, “We’re used to it. We’ve been doing this for a while now.”

In pharma, it’s not as if the down economy started the whole feeding frenzy. It goes back more than a decade. In the Towers Watson surveys, greater numbers of pharma workers reported no “direct impact” as a result of a merger or acquisition. “The majority of folks are still doing the same job, with the same ‘comp and ben’ as they had prior to acquisition,” says Giampietro.

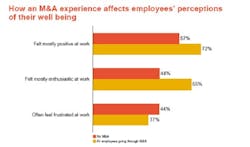

In addition, says Cianni, pharma’s professionals tend to be optimistic about M&A’s (see Figure 1), that this change may “offer more global experiences, in new therapeutic areas, and translate their skills and experiences into new opportunities and challenges.”

Figure 1. How an M&A Affects Pharma Employees’ Well Being

What’s more, these workers feel a greater sense of well-being than those pharma peers who have not undergone such a tumultuous change. This is not generally true to form in other industries, the two say.

Those same workers (that is, those in pharma that have an M&A in their past) also have a greater sense of their firm’s well-being, that it is sticking to its values and goals. The merger or acquisition, in other words, was part of executing a long-term strategy.

The Rest of the Story

But Cianni qualifies this rosy data: Because the survey was conducted via employers, the respondents are those who are employed and, theoretically, have not been badly burned.

Also, Towers Watson data shows that while pharma employees may handle a merger or acquisition period deftly, that doesn’t mean they don’t fret about what the future holds. For instance, those pharma workers who have gone through the M&A wringer express more uncertainty about their futures and their potential for advancement, and are thus more open to possible job offers, than do those who have remained under a single, consistent employer. They also express doubts about whether or not their new (or newly structured) company can meet their desires in terms of pay and long-term security.

To alleviate such fears, Cianni and Giampietro say that workers are looking for an “emotional connection” with their superiors during times of transition. Emotional connection? Is it reasonable to expect some kind of special bond between shop-floor Stu and C-suite Cheryl?

No, says Cianni. Workers just want to know that their execs are there for them. “When senior leaders are making decisions, is there a recognition of what the human impact on employees will be?” she asks.

Pharma execs, it seems, know this. “Many of our clients who are serial acquirers take away lessons learned from each merger or acquisition on how to do it better,” Cianni says. “There has been a learning along the way on how to lead through change.”

This learning now needs to be communicated to middle management. They’re the ones who serve as both conduit and buffer between the majority of workers and executives. If they break down, the M&A can break down.

“Senior management now understands how important it is to be visible all the time and make that emotional connection all the time,” says Giampietro. “Now it’s a matter of understanding not only how they need to lead but how they can support other managers in leading.”

Take it as a sign of hope, wherever you are employed in pharma, that we’re getting good at M&A’s. Who knows, maybe even this Roche-Genentech thing can work.