Though medication non-adherence has been discussed with growing interest for several decades, the topic remains an important focus of the pharmaceutical industry. In 2012, it is estimated that 8% of the total healthcare spending in the United States – more than $200 billion – was spent on improper or unnecessary use of medications.1 Though many different patient subsets continue to be affected by poor adherence, children present a unique challenge.

Children remain a distinct challenge because of their fluctuating development, as well as the variable number of caregivers and treatment locations that may be involved.2 In the United States alone, more than 200,000 out-of-hospital medication errors per year have been reported to the National Poison Data System (NPDS), the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ (AAPCC) proprietary database since 2003. Approximately 30% of those reports have involved children 6 years of age or younger.3

Improving medication adherence requires the active participation of all involved parties. The pharmaceutical industry is well positioned to enact change at this level by focusing on formulations, simplified dosing regimens and packaging improvements to enhance caregiver convenience and understanding.

Significant Dosing Challenges

Children and adolescents are often physically limited in their ability to ingest larger solid dose medications, which has led pharmaceutical manufacturers to consider alternate forms of administration; different or limited taste preferences also pose a challenge.2 Syrups and suspensions offer greater flexibility, as a dose can be adjusted to account for weight or flavored for taste. However, both are also difficult to measure, easy to spill if a child is resistant, and offer little in the way of tracking from one dose to the next. Ensuring that accurate dosing cups, spoons, oral syringes, or droppers are provided can help to improve accuracy and eliminate the use of household measuring devices (e.g. teaspoons).

Of the medication errors documented in the NPDS from 2002-2012, over 80% involved liquid medications.3 Additionally, 20% of all dosing errors were categorized as the result of an accidental double dose.3 Offering multiple dosing options – tablets/capsules, chewables, granules and/or injectables, along with suspensions and syrups, can help to minimize many of the issues associated with liquid dosing; but dose size and accuracy are only part of the challenge.

The physiological differences in children may make certain excipients unsuitable for pediatric consumption, presenting an entirely different set of challenges for pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturers.2,4 A child’s size changes dramatically – an increase of up to 1900% during growth; the dose increase that should correspond with this may approach 100-fold.4 This leads to significant pharmacokinetic differences in young children, including drug metabolism, transport expression, renal clearance, gastrointestinal permeability, and drug absorption (based on surface area).4 With many of these differences constantly in flux, it can be difficult to ensure that a given medication will meet toxicity and excipient requirements. Thoroughly understanding pharmacokinetic impact on pediatric patients is important, but pediatric drug testing adds to development costs and has only recently started to increase.

Market Challenges

The pharmaceutical industry has historically viewed the pediatric market segment as only offering small financial benefits.5 To further complicate the issue, studies conducted on children present unique challenges related to both informed consent – with children 7 years of age and older being allowed to independently assent or dissent – and challenges with even the most routine procedures, including blood draws and urine samples.5 However, FDA regulations are working to increase pediatric studies to benefit patients and pharmaceutical companies alike. Though these studies place added responsibility on manufacturers, they help clinicians make more informed decisions, offering caregivers additional peace of mind.

In particular, the voluntary Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) has been significant, potentially offering six months of additional marketing exclusivity on drugs in pediatric studies, as well as all additional forms / formulations containing the same active-ingredient moiety.5 Both pharmaceutical companies and the FDA can initiate a pediatric trial under BPCA, but the FDA ultimately determines the potential pediatric health benefits of the drug. However, after voluntary measures in the 1990s failed to produce results, the FDA became aware of the need for mandatory research in addition to voluntary programs and, as a result, the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA) was signed into law in 2003. PREA aims to protect pediatric patients by allowing the FDA to require pediatric studies on both pharmaceuticals and biopharmaceuticals if it believes the substance will likely be used in a pediatric setting or could provide benefits in such a setting.5

Patient-Friendly Packaging and Labeling

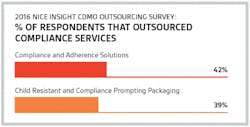

Following trials, one of the most significant ways pharmaceutical manufactures can help combat non-adherence is through improvements to both primary and secondary packaging. According to the 2016 Nice Insight CDMO Outsourcing Survey, many manufacturers are already turning to manufacturing partners for solutions in this area; compliance and adherence solutions were outsourced by 42% of respondents, while 39% outsourced child resistant and compliance prompting packaging.6

For primary packaging, single-use options are perhaps the most viable way of reducing dosing errors. Though all patient demographics benefit from the ease and accuracy of single-use packaging, children may be dependent on multiple caregivers in multiple locations. As the modern lifestyle becomes increasingly mobile, the portability of single-use helps ensure that medication is administered correctly, regardless of who is responsible for the dosage.7

Additionally, single dose packaging is suitable for oral, topical, and injectable medications.7 Blister or pouch packaging are frequently used for solid dose medications (e.g. capsules, gels, tablets, etc.) and can also be perforated for easy separation and transportation of individual quantities.7 For solutions, suspensions, stick-packs, gels and powders are ideal because no delivery devices are required, the pack material is highly durable allowing for safe manufacture, shipment, and caregiver handling, and the packs are easy for children to open.7 Stick-packs also reduce the risk of spilling. Further, single dose dispensing is often more sanitary; drug contamination becomes less likely as each dose is individually packaged.7 Finally, single dose packaging offers potential pharmacokinetic benefits, including a decrease in the number of ingredients in a given medication as it reduces or eliminates the need for preservatives.

Packaging readability is also a critical component of patient adherence. Drug labeling is the primary guidance for clinicians, healthcare professionals and caregivers, and it remains with the medication for the duration of its use. New trials, often as a result of both BPCA and PREA, offer dosing guidance for several medications. Highlighting these changes can help improve prescription accuracy and dosing effectiveness. With the recent surge in pediatric studies as compared to prior years and decades, labeling has been updated on over 80 medications, including ibuprofen – one of the most common over-the-counter pediatric drugs that originally offered no guidance for patients 2 years of age and younger – Zantac, Claritin syrup, and Pepcid in various forms.5

Though considerable progress has been made in the way of pediatric medication administration, non-adherence numbers are higher than ideal. Despite an increased focus on the issue, additional work is needed to help guarantee patient safety. The FDA continues to work with pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturers to increase the number of tests covering the pediatric space, examining everything from study ethics to pediatric oncology trials, and working in tandem with the American Academy of Pediatrics to keep clinicians aware of labeling changes and significant improvements that can impact patients.5 Ultimately, these efforts offer promise to pediatric patients and allow parents to feel more secure about the treatments they are providing to their children.

References

- IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics., Avoidable Costs in U.S. Healthcare: The $200 Billion Opportunity from Using Medicines More Responsibly. Jul 2013. https://www.imshealth.com/en/about-us/news/ims-health-study-identifies-$200-billion-annual-opportunity-from-using-medicines-more-responsibly

- Ivanovska, V., Rademaker, C., van Dijk, L., and Mantel-Teeuwisse, A., Pediatric Drug Formulations: A Review of Challenges and Progress. Aug 2014. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/07/09/peds.2013-3225.full.pdf

- Smith, M., Spiller, H., Casavant, M., Chounthirath, T., Brophy, T., Xiang, H., Out-of-Hospital Medication Errors Among Young Children in the United States, 2002–2012. Nov 2014. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/10/15/peds.2014-0309.full.pdf

- Chappell, F., Medication adherence in children remains a challenge. Jun 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/psb.1371/asset/psb1371.pdf;jsessionid=FCBA1FCC0624AA5859CF996F98A024DE.f01t03?v=1&t=inga7rl0&s=24caa5ebd8ccfe81b00ca6f19cdb3c0bc283a8d9

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., Drug Research and Children. May 2016. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm143565.htm

- The 2016 Nice Insight Contract Development & Manufacturing Survey. January 2016.

- Haehl, K., Choosing the Optimal Drug Delivery System to Meet Patient Needs. http://www.niceinsight.com/articles.aspx?post=2772&title=Choosing+the+Optimal+Drug+Delivery+System+to+Meet+Patient+Needs+