One of the great medical discoveries of all time was born from innovative Canadian research.

When four Toronto researchers (Banting, Best, Collip and Macleod) discovered, developed and tested insulin, they created the first effective treatment for diabetes — revolutionizing the standard of care and undoubtedly saving millions of lives.

The development of insulin was a bright spot in Canada’s rich history of scientific discovery.

But if the country is going to reach the ambitious goals laid out by the federal government two years ago — doubling the size of the health and biosciences sector and becoming a top-three global hub by 2025 — the pharma industry will have to push beyond its core competency.

“When you look at our ecosystem it’s done a fantastic job of generating a lot of early stage companies, but unfortunately we’ve failed to take a lot of those companies across the finish line,” says Andrew Casey, president and CEO of BIOTECanada, a national association whose mission is to lead the advancement of the Canadian biotechnology ecosystem.

Hindered by a complex regulatory environment and conflicting policy direction regarding drug pricing, the pharma industry has its work cut out for it. But many believe the industry — described by Casey as “diverse and deep in its nature” — is up to the task.

Lofty goals

Announced in 2017, the Canadian government’s Innovation and Skills Plan was focused on making the country a world-leading center of innovation by supporting economic growth in six key sectors, health and biosciences being one of them. Part of this plan included a new model for industry-government collaboration, which in turn produced the Health and Biosciences Economic Strategy (HBEST) in 2018.

At the time, Canada ranked fourth in global health and biosciences hubs, behind the U.S., U.K. and Germany. The HBEST action plan laid out several economic growth targets for the Canadian pharma industry including doubling health and biosciences exports to CA$26 billion (~$20 billion USD) and doubling the number of companies to 1,800.

According to Casey, even pre-COVID, these HBEST objectives were a “stretch target.” But given the industry’s strong foundation — a globally recognized capacity for scientific research — he still believes the goals are within reach.“The plan recognizes some fantastic existing strengths in the Canadian ecosystem and the desire to push the industry even further,” says Casey. “It is a way of challenging every part of the ecosystem to do a better job recognizing that we do have a very strong foundation upon which to build.”

Getting to market

A well-known obstacle when it comes to bringing drugs to the Canadian market is the country’s lengthy marketing approval timeline. And while Health Canada’s drug approval process is frequently criticized for being slower than its American or European counterparts, the regulator is just one part of a sequential, time-consuming process.

After Health Canada evaluates a drug candidate for safety and efficacy, the approved drug must then undergo a health technology assessment through the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Established by the federal government, the small but powerful independent agency is responsible for making recommendations to the provinces and territories about treatments accepted for public drug plans.

Following the CADTH review, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA), an alliance of provincial, territorial and federal governments, steps in to conduct joint negotiations for drugs (both brand and generic) in order to achieve the best value for publicly funded drug programs and patients.

“Getting these steps compressed has been difficult. It’s getting better but still could be significantly streamlined. There’s movement afoot to deal with it but as long as it remains separate entities, it’s always going to be a challenge,” says Casey.Pharma hates uncertainty

But a labored drug approval process is not what is holding the industry back from achieving the government’s economic goals. In fact, many argue that government itself is handcuffing the industry with new price control measures.

Last year, the Canadian government passed what is being touted as the biggest reform to the country’s drug pricing policy in over 30 years. A hotly debated policy issue, the amendments to the Patented Medicines Regulations are currently set for implementation on Jan. 1, 2021, after COVID pushed the original July 2020 date.

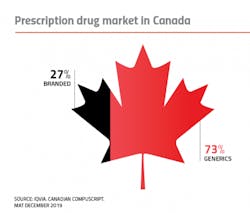

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) conducts ongoing reviews and, if necessary, investigations of individual patented drug prices to make sure they are not excessive. In short, the reform will change how the federal agency calculates the fair price of branded prescription drugs (notably excluding countries with high prices, such as the U.S., as price comparator countries) and enable the agency to consider the cost-effectiveness of new medicines. Proponents say the adjustments will reduce the list prices of current and future branded meds in Canada by an average of 20 percent, saving patients US$10 billion over the course of a decade.

But critics — among them, the pharma industry — says this siloed approach to reducing health care spending is limiting Canadian’s access to innovative medicines, as well as creating an inhospitable environment for investment.

“Uncertainty created by policy process, like the amended PMPRB regulations, gives companies pause when or if they bring products to the Canadian marketplace,” says Casey. “Pharma hates uncertainty.”

Perhaps more concerning is the indirect effect that pricing uncertainty could have on the overall pharma ecosystem in Canada. The majority of large branded pharma companies in Canada are foreign multinationals with Canadian subsidiaries. Of the top 20 selling drug corporations in Canada, only Apotex, Bausch Health (formerly Valeant), Pharmascience and Teva Canada (formerly Novopharm) are Canadian-based.

The presence of commercially active multinational companies looking to replenish pipelines creates opportunity, as they provide a vital source of capital and support for smaller, early stage companies in Canada. Pharma-led investments and partnerships have led to the maturation of several significant Canadian companies with a number now poised to become commercially active.

But these investments and partnerships taking place in Canada are at risk through the new pricing dynamic.

“If you make this market uncomfortable and unattractive for large multinationals, they will change their business practices. They will likely decrease their investments and partnerships in Canada — and that’s problematic. Maybe clinical trials start slowing down as well. It’s a slippery slope,” says Casey.

Ripple effects

The government push to drive drug prices down to the lowest possible price line in Canada is creating an effect felt beyond the Canadian borders. Critics of the new pricing policy see it as a disservice to the global pharma industry as a whole.

“Our drug prices have to stay aligned with the global marketplace,” says Casey. “In some ways, what is happening in the U.S. reflects the fact that we are allowing the Trump administration to point us out as bad actors.”

What Casey is referring to is an executive order, part of four orders designed to lower the price of prescription drugs for U.S. patients, signed by President Trump in late July. If implemented, the Executive Order on Increasing Drug Importation to Lower Prices for American Patients will allow for the commercial importation of certain prescription drugs from Canada.

While the real-world implications of this order may be fairly limited — only a small subset of drugs are able to be imported under the statute — it does highlight a large disparity in prices between countries.

For years, Americans have routinely skirted federal law by tapping online pharmacies in Canada to buy prescription drugs at a fraction of the price they would pay at home. While the Trump EO does not address personal importation, this practice has led to considerable concerns about drug safety, exposing American patients to nefarious characters as drugs travel across borders — an issue that critics of the new EO say could be seen at the wholesale level as well.Wholesale imports of drugs from Canada also raises supply concerns for the Canadian pharma industry. The country already has a pharmaceutical trade deficit: In 2019 Canada imported US$13.9 billion worth of drugs, versus the $8.4 billion it exported. A previous study predicted that if 20 percent of U.S. prescriptions were filled using Canadian sources, the demand from the U.S. for patented drugs would deplete the Canadian branded drug supply in just 201 days.4

In addition to causing supply shortages for Canadian patients, importing drugs from Canada would likely do little to ease the price burdens in the US.

“Let’s say, hypothetically, you were able to take every single pill out of Canada, I’m not sure you’d have enough to address the problem in a county in Florida, let alone the entire U.S.,” says Casey.

The timing is right

The Canadian pharma industry continues to push back on the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board’s modernized regulatory framework, contributing alternate proposals that the industry feels can address health care fiscal challenges while also supporting pharma’s business model. So far, the industry has been unsuccessful in achieving the type of change it wants to see and many fear the extent to which the new regulations will impact the country’s ability to attract investment to commercialize Canadian innovation.

However, the pandemic, as we all know, has changed much in the world. Unfortunately, some economic sectors that previously generated high amounts of revenue may be slow to recover, if at all. And many are wondering how countries will compensate for this loss in revenue.

“I look to innovation and biotech, certainly the pharma and biotech industries, as potential replacements for some of that,” says Casey.

Economic recovery and a return to any semblance of normalcy hinges on testing, treatments and vaccines — and the global pharma and biotech industries have mobilized at unprecedented speeds to make this possible.

Casey hopes that pharma’s progress will create a new appreciation for the value the industry brings, and that, in turn, may influence policy in Canada.

“In this paradigm is there an opportunity for a new discussion that is a bit more holistic and not so narrowly focused on pricing? I hope so,” he says.

Overall, if the Canadian pharma industry wants to achieve big goals by 2025, it will take a combined effort from industry and government. Government policy can help or hinder the pharma industry’s ability to attract the investment and capital needed to support a thriving market for pharmaceuticals.

“If a good idea isn’t attracting investment where it is, that good idea will go to where that investment is and we will lose out on the commercialization of that product,” says Casey.

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'