You’ll hear people say that pharma is “going green,” but in many ways it’s already there. The drug industry has taken great strides in environmental conservation. In Newsweek’s recently released Green Rankings, pharma places third among all sectors. J&J places third among all manufacturers with Bristol-Myers Squibb and Allergan in the top 20.

The drug industry is on the cutting edge of green, says Walt Tunnessen, national program manager for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program. “Corporate social responsibility is extremely important in the pharmaceutical sector,” he says. “Big pharma companies are at the forefront of climate initiatives, and yet the sector is a blip on the radar in terms of overall emissions.”

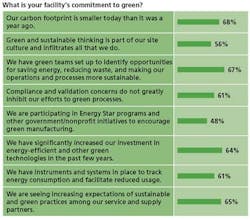

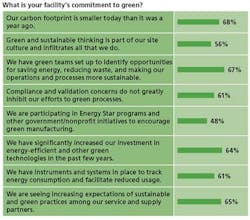

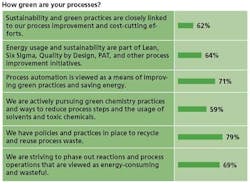

We conducted some informal surveys of our online readers (see Boxes), and found some interesting data:

- Three-quarters of respondents said their companies’ executives are committed to sustainability and have communicated a clear green strategy to employees.

- More than three-quarters said that all of their company’s facilities have green initiatives in place and contribute to idea-sharing across facilities.

- Roughly two-thirds say that employees are appropriately rewarded and recognized for furthering corporate green and sustainable initiatives.

- Roughly two-thirds say that their companies’ carbon footprint has shrunk within the past year, and that their facilities have significantly increased investments in energy-efficient and other green technologies.

- More than 50% say that their companies have dedicated corporate energy directors and energy teams

While our numbers are not statistically significant, they do provide a broad picture of how green pharma manufacturers are, and in what areas.

Not all the numbers were glowing:

- Just 40% said that there is accountability for employees and projects that do not meet green or sustainable expectations.

- Only 50% said that their facilities are participating in government/nonprofit initiatives to encourage green manufacturing.

Still, pharma has energized its green efforts, especially in the area of energy management. Most major manufacturers have comprehensive energy management programs, and this year, for the first time, four pharmaceutical plants—two from AstraZeneca and one each from Schering-Plough and Allergan—were given Energy Star ratings for top performance. “Five or six years ago, there was a lot of variability within big pharma companies,” says Tunnessen. Not so any more, as energy prices have continued to rise, companies have committed to reducing their carbon footprints, and to reducing operating expenses across the board.

It’s an ongoing process. “We’re still working to improve methods of tracking and trending energy,” says Chaz Calitri, senior director of Pfizer Global Engineering. “Some sites in our network are very sophisticated, but most still use a hybrid of manual and automated systems. Our ultimate goal is to be able to track all of the sites centrally in real time. I am not aware of any companies of our size that do this today; however, we believe that this long-range goal is reasonable and achievable.”

And Pfizer, like many large manufacturers, realizes that its green goals are rooted in culture change. “If we can mobilize every Pfizer colleague to be more conscious of energy use (and energy waste), we will realize tremendous energy savings and accompanying business benefits,” Calitri says.

What happens at Pfizer and its peers has not necessarily trickled down to small and mid-sized manufacturers, who may lack the wherewithal to systematize their energy practices.

Our informal survey reflects this:

- Roughly 85% of respondents at large companies (those with over 1,000 employees) say that executives have formulated and begun to implement a meaningful, corporatewide green strategy, whereas less than 50% said this is the case at smaller manufacturers (less than 1,000 employees)

- Roughly three-quarters of those at large manufacturers said their company’s carbon footprint was smaller than a year ago, while half at smaller manufacturers said the same.

All manufacturers will need to improve. While critics might say that corporate environmental responsibility is “greenwashing,” merely for good PR, it’s widely held that going green is a business imperative. Reduced energy usage, for instance, means lower operating costs and less exposure to fluctuating energy prices, and regulatory requirements upon manufacturers to reduce carbon footprints will increasingly pressure small and large manufacturers to step up. There is really no choice.

The Stars Are Aligned

Many factors are conspiring to bring energy issues to the fore of drug manufacturing, not the least of which has been elevated energy prices. At Wyeth’s 300-acre Pearl River facility, its largest, last year’s surge in prices kicked the facility’s green initiatives into high gear, says Bill Edsall, the site’s energy manager. “Cost was the big driver,” he says. (In our survey, 90% said that cost savings were driving their green initiatives.)

The key green metric by which Wyeth gauges itself is CO2 output, and Edsall says Pearl River’s emissions have dropped 14% in two years. (The company’s goal is to reduce overall emissions by 10% by 2012, though the bar may be raised following the Pfizer-Wyeth merger. “From an energy management perspective, I’m looking forward to the merger,” Edsall says. “Pfizer’s always been a bit more aggressive than we have.”)

Edsall has money in his annual budget for metering, and has overseen efforts to upgrade metering at all electrical substations, and for most steam operations. (“Steam is a tough animal to maintain,” he says. It’s a 24/7 operation that’s hard to shut down.) Meanwhile, most production buildings have metered equipment. “I know what my air compressors or chillers are doing,” he says.

Air compressors and chillers have long been considered the low-hanging fruit for reducing pharmaceutical energy usage. So has lighting. Pearl River worked with Orion Energy Systems to replace all the low-pressure sodium lights in one warehouse with energy-efficient, sensored lighting—ROI on the project was just a year, Edsall says.

But in Pearl River, as at most facilities, there is no such fruit in GMP areas. “I don’t know what my blenders and fillers are doing,” Edsall continues.

The idea of adding new equipment, or perhaps retrofitting old, inefficient lines and equipment, stirs fears of revalidation (and associated costs). “Some people think that there’s nothing you can do [without revalidating],” says EPA’s Tunnessen, “and that they can only tweak things around the periphery,” Tunnessen says.

That’s true, but manufacturers with proactive energy programs learn to take advantage of opportunities for upgrades. “A lot of it is timing,” Tunnessen adds, “of making efficiency upgrades when the opportunity presents itself,” such as when a line is being reconfigured or a new piece of equipment is being purchased.

That’s been the case at Wyeth Pearl River, says Edsall. Energy efficiency upgrades are usually “back-burnered” in GMP areas, until there’s an opportunity for change. “If you’re going to make changes for any reason, that’s the time to incorporate [energy upgrades],” he says.

Public and Private

Wyeth has also benefited from support from the public sector. It worked with a consultant from NYSERDA (the New York State Energy and Research and Development Authority) to install variable-primary loops in its chilled water systems, for example.

The EPA has been the biggest champion of energy change, namely in the creation of an Energy Star program for drug facilities to aspire to. Another significant development has been the establishment of a pharma-specific Energy Performance Indicator (EPI), now available on the EPA web site. The EPI is an Excel-based tool that relies on specific data about factors such as plant size, hours of operation, annualized energy purchases, heating and cooling degree days.

While the EPI is being used as a measuring stick for facilities seeking Energy Star recognition, it’s also a means for manufacturers to get a sense of where they stand in comparison to peers, and to discover what they can improve upon. The EPI allows manufacturers to compare cross-facility comparisons, intra-facility comparisons among different spaces, and to perform modeling and manipulations.

And while the EPI was developed with U.S. facilities in mind, manufacturers are using it to benchmark their global operations, says Duke University statistician Gale Boyd, who spearheaded the development of the Pharma EPI.

There are public-private initiatives taking place across the globe, on multiple levels, to encourage sustainability, from regional energy councils to organizations that promote “triple bottom line”—people, planet, profit—business practices. A new project worthy of mention is Labs21, or “Laboratories for the 21st Century,” an informational and educational program co-sponsored by EPA and DOE to improve the environmental performance of laboratories, particularly where energy and water usage are concerned. (More info is at www.labs21century.gov.)

Another collaborative effort has been the development of an impending ISO 50001 standard, now in draft form, that will establish a framework for industrial facilities (as well as commercial) to manage energy. Having an ISO standard in place will go a long way towards encouraging pharmaceutical manufacturers to step up.

Vendor Upgrades

Energy consciousness has also become marketable, and so most major vendors working with drug manufacturers are promoting their value as green partners. (In Newsweek’s green rankings, two key pharma vendors, Agilent Technologies and Pall Corp., led all companies in the Industrial Goods sector.)

There’s more of a market for sustainable practices these days, says Marcia Walker, program manager for Rockwell Automation’s Sustainable Production Solutions. Manufacturers are moving from projects that focus on the low-hanging fruit to those that take a more comprehensive approach. “The next step for any real savings is going to have to be on the industrial side,” says Walker.

In the past, she says, industrial energy consumption was typically viewed in terms of a given allocation per square feet of plant space. That won’t fly any more, as pharmaceutical companies are under much greater regulatory pressures. In the U.S., that means not only FDA pressure regarding product and process risk, but also pressure from the Department of Energy, EPA, and other federal agencies.

The problem is, Walker says, that manufacturers have tended to view sustainability in limited terms—turning off lights, installing solar panels, recycling waste—saving energy and implementing green practices here and there. The classic case is one in which corporate leadership institutes sustainability goals, but by the time those goals get translated to the plant floor, there is little clarity and substance to them.

Manufacturers will have to understand their energy usage at the line and equipment level, Walker says. For most, “it’s a big guess. If line 1 were using three times as much energy as line 2, most manufacturers wouldn’t know it.”

Naturally, this becomes more difficult for smaller manufacturers with fewer resources. Less than 40% of respondents at manufacturers of less than 1,000 employees said that they have significantly increased investment in energy-efficient and other green technologies in the past few years. Nearly 80% of those at larger manufacturers said they had upped such investments.

Dovetailing

Energy management also dovetails nicely with the transformative initiatives taking place in the pharmaceutical industry, such as Process Analytical Technologies (PAT) and Quality by Design (Qbd) and Lean Six Sigma, and continuous manufacturing, and with trends such as the overall movement towards outsourcing of non-core competencies.

The potential to use PAT for energy monitoring is one exciting development taking shape. Energy saving is usually a “frequent, collateral” reason for using PAT, says consultant John Carroll, one of this magazine’s editorial advisors. He uses the example of fermentation: If you monitor and control key parameters, you can shut down the fermenter as much as a day or two earlier than usual. For a biopharma plant that has a dozen or two 15,000-gallon vessels, the power and cost savings can be staggering, Carroll says.

Carroll has witnessed this first-hand (though he can’t say where), in which operators used a combination of real-time metrics—dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, and glucose—to estimate the completion of batch fermentation and shut down equipment early.

The idea holds for small molecules as well, Carroll says. If bin blenders, granulators, fluid bed dryers and other process “energy hogs” can be made more efficient via PAT, the payoff will be rapid.

Energy management will also prod the transition from batch to continuous manufacturing, he adds, since continuous operations use less energy to begin with and scale up more easily and efficiently than batch. Energy management and energy savings are a critical part of the economic analysis when converting from batch to continuous processes, agrees James Evans, associate director of the Novartis/MIT Center for Continuous Manufacturing.

Outsourcing and Due Diligence

Pharmaceutical OEMs and solutions providers are thinking green and making energy management part of their selling point. Sometimes, it’s their primary focus, as for Rockwell. Vendors are supporting energy management, and in some instances it’s being outsourced completely to building management specialists.

This summer, contract manufacturer Patheon announced that it was outsourcing the energy management of all its facilities to Canadian firm Emcor, in order to standardize energy management and maintenance across multiple facilities—a move it says could save it more than $3 million over the next year and a half. The deal with Emcor is part of a comprehensive plan at Patheon, based upon Lean Six Sigma principles, to eliminate waste throughout the company.

Energy costs have become a key factor in contract manufacturing negotiations, consultant Carroll notes. The key decision point regarding whether or not to outsource is cost, he says, and ability to save on energy costs ranks with savings related to personnel, inventory, and manufacturing capacity.

“Energy is at the forefront of consciousness” in all of pharma’s decisionmaking these days, Carroll says, “where it might not have been a few years ago.”

Where’s the Trickle Down?

Contract manufacturers should have no problem seeing the value of becoming more energy efficient. What about other small-scale manufacturers, whether in branded pharmaceuticals, biotech, or generics? Are they ready and willing?

While Big Pharma is clearly on board with the Energy Star program and are using the pharma EPI, smaller manufacturers remain hesitant, Boyd and Tunnessen say. For one thing, getting an accurate read on a facility’s energy usage requires the right technology, and a “certain amount of submetering” that most plants are not equipped to do, Tunnessen says.

Another scenario is that smaller manufacturers don’t know what they’re missing. The EPI, for instance, is a “reality check,” says Boyd. Some manufacturers realize that “what they thought was great is really just average.”

And some manufacturers may not want to know. When manufacturers investigate their energy practices, or use a performance indicator as a gauge, it increases transparency at the corporate and individual level. “People are afraid that this tool [the EPI] could be used to show they’re not doing a good job,” Boyd adds.

The greatest challenges, however, are getting the word out and raising awareness, say Tunnessen and Boyd. For most small- to medium-sized manufacturers, “there just isn’t anyone steering the ship with energy management,” says Tunnessen.

In our survey, half of respondents at smaller manufacturers said that they didn’t have a corporate energy manger or someone specifically dedicated to energy management. “The issue with smaller manufacturers in particular is that they don’t know what they don’t know,” Boyd says. “The exercise of collecting information may show things that they have never looked at before.”