It started with an impassioned appeal for survival. Staring down a terrifying diagnosis with an average life expectancy of one year, patients and their advocates were screaming for a cure.

During the gap between the first published cases of severe pneumonia infecting otherwise healthy gay men in the summer of 1981 and the first Food and Drug Administration-approved medication in March 1987, over 40,000 cases of AIDS were reported to the World Health Organization. The agency estimated that it was likely that 5 to 10 million people were living with HIV infections worldwide.

Pharma companies began scouring their shelves, looking for compounds with the potential to combat AIDS, while cases and deaths continued to catastrophically mount. Burroughs Wellcome sent its nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, azidothymidine (AZT) — which failed years earlier against cancer but had showed promise against mouse and cat retroviruses — to the National Cancer Institute for further testing. Just six months after favorable lab reports from NCI, in July 1985 AZT was injected into a human for the first time — 20 months later, it had the first FDA approval.

The historically controversial approval — which at first was limited to only those who were severely ill with AIDS — brought about broader realizations about what science was up against in the AIDS fight. AZT’s toxicity led to brutal side effects and over time, patients began developing viral resistance to the drug. Although crucial to paving the way for future treatment regimes, it quickly became clear that AZT alone provided only modest benefit to those dying from AIDS — and certainly was not the silver bullet cure for which patients had been hoping.

Focus shifted towards finding new and safer treatments — and combinations of treatments — that could more effectively treat both HIV and AIDS. While the quest for a cure was never abandoned, many in the scientific community argued that given the constantly mutating virus and its stealth ability to hide in cell reservoirs, a cure might never be possible.

Now, over 40 years later, the FDA has approved more than 60 drugs in the buzzing HIV treatment and prevention space. With combination drug treatments started early, people living with HIV can not only survive but can potentially remain undetectable and unable to transmit HIV — living near-normal lifespans. Despite three isolated cases of individuals cured of HIV while undergoing invasive treatments for cancer, a scalable cure has yet to be found.

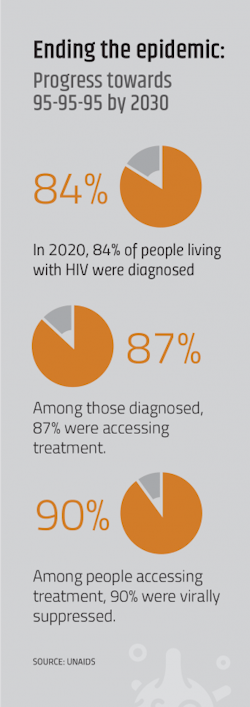

But the voices of those living with HIV are still ever-present and many engaged in the fight have united in an ambitious goal: ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The target year is 2030. In the U.S., there are two national plans in place to help stick to that timeline. Globally, the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has set the same 2030 deadline.

There are many parameters being used to define the epidemic’s ‘end’ and just as many plans to get there. But few, if any, federal or global initiatives expressly specify the need for a cure.

Pharma, however, has its own plan. Within the industry, optimism is high regarding the feasibility of ending the HIV epidemic. This race to the end has become a delicate — and at times, conflicting — balancing act between the hunt for continued innovation in a crowded treatment space and the ongoing, collaborative search for a cure. Ultimately, pharma’s ability to weigh these pursuits could pay off exponentially for both the industry and people living with HIV.

A formula for the end

The succinctness of the call to ‘end HIV by 2030!’ makes it highly effective as a rallying cry, but confusing as a quantitative goal. Ultimately, the objective is the end of HIV/AIDS as an epidemiologically-defined term, using certain criteria to measure progress. In the U.S., the HIV National Strategic Plan uses viral suppression as the main indicator of success. Specifically, the U.S. goal is for 86% of people living with HIV to be virally suppressed on antiretroviral treatment by 2030.

If no other factors were considered, epidemiologically, HIV could end without a cure. Given how lucrative the HIV treatment space has been for pharma companies (the industry’s top-selling treatment, Gilead’s single-tablet blockbuster, Biktarvy, is predicted to achieve sales of around $11 billion by 2025) it may seem contradictory that a company would pursue something — in this case, a cure — that could, in theory, make treatments obsolete.

But taking into consideration the vast amount of human lives affected, the myriad variables that come into play in the complicated HIV treatment landscape, and the commitment to end the epidemic by 2030, many pharma companies active in the HIV market have made the hunt for a cure a dedicated part of their epidemic-ending plans.

Pharma’s approach to ending the epidemic has evolved over years of observing the patient experience, and that evolution has brought the industry closer to a cure

Currently, an estimated 38 million people are living with HIV, facing a lifetime of antiretroviral therapy.

“The need for lifelong treatment of HIV with antiretroviral therapy poses multiple challenges for people living with HIV (PLWH),” says Brian Plummer, a spokesperson for Gilead Sciences.

PLWH often struggle with treatment fatigue or pill burden. Side effects from lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens can include weight gain, muscle pain, nausea and insomnia. Living with HIV also means confronting numerous social and psychological challenges.

The confluence of these factors can lead to poor drug adherence, which can result in drug resistance and suboptimal viral suppression rates — a direct contradiction to epidemic-ending goals. On the flip side, heavily treatment-experienced patients may also struggle to maintain viral suppression with currently available medication due to drug resistance.

Additionally, while the scientific advances made in the HIV space have fortunately led to substantial improvements in the life expectancy of people living with HIV, this too comes with challenges and a new set of considerations.

“The corollary of a longer lifespan is that PLWH are now faced with an increased risk of developing comorbidities and chronic diseases associated with aging, in addition to chronic HIV. Chronic comorbidities may also contribute to a greater pill burden and additional complications, which may negatively impact adherence to HIV therapy,” says Plummer. “Achieving a cure would have a dramatic impact on the challenges associated with lifelong treatment and the social stigma associated with HIV and is key to accomplishing the shared goal of ending the HIV epidemic.”

But lacking immediate prospects for a cure, the pharma industry has looked to address unmet patient needs with innovative, more convenient treatment solutions.

According to Kimberly Smith, M.D., MPH, head of R&D for ViiV Healthcare, “For the past decade, it felt like we had reached a plateau in how we treated HIV with once-daily oral HIV medicine. Once-daily oral medicine has been and remains the bedrock of our approach to treatment, but for many individuals, it can be challenging and to continue our progress towards ending the epidemic, we must look for innovative options beyond daily medicine.”

Davinderpreet Singh Mangat, Informa Pharma Intelligence senior analyst with a focus on infectious disease research says a change in treatment paradigms is already underway.

“There will likely be a continued shift towards developing long-acting regimens and that will become the new normal in 5-10 years’ time,” says Mangat.

ViiV’s Cabenuva, approved by the U.S. FDA in January 2021, was the first-ever, long-acting HIV treatment. It is administered via injection every two months instead of daily, significantly reducing dosing from 365 to as few as six times a year. ViiV — which was born out of a partnership between GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer in 2009, with Shionogi joining in 2012 — anticipates that between 10% and 15% of eligible patients will switch to Cabenuva from daily oral therapy.

Gilead’s most recent prospect, lenacapavir, is an investigational, long-acting HIV capsid inhibitor that could also facilitate treatment adherence by increasing dosing convenience. Lenacapavir is currently being investigated for use alone for HIV prevention or in combination with other antiretroviral agents for HIV treatment; as oral or injectable delivery, with potential multiple dosing frequencies, some as little as twice per year. (While Gilead recently hit a regulatory snag when the FDA declined to approve the treatment due to lenacapavir’s compatibility with the vials it’s stored in, the drugmaker is working with the agency to rectify its vial problem.)

“The next major breakthroughs will be about providing options that allow people to go even longer between their HIV treatments, like medicines administered twice or even once a year,” says Smith.

These treatment innovations have also helped nudge pharma closer to a cure. Functional cures — a scenario where treatments trigger long periods of viral remission in the absence of ART — could advance progress a step further than current long-acting treatments, potentially allowing people to go years between taking medicine.

Keeping tabs on the cure market

Despite the long-standing buzz surrounding the hunt for a cure, quantifying that interest — especially from the pharma industry — is challenging.

Leaders in the pharma space have backed their commitments to a cure with large amounts of funding initiatives and philanthropic endeavors.

For example, Gilead’s HIV cure grants program has awarded more than $29 million in grants to academic institutions, non-profit organizations and community groups engaged in HIV cure activities since initially announced in February 2016. ViiV Healthcare and GlaxoSmithKline have collectively invested $40 million into a collaboration with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, out of which came Qura Therapeutics and a dedicated HIV Cure Center.

The AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition (AVAC) and the International AIDS Society’s most recent Global Investment in HIV Cure Research and Development report indicated that global investment in cure research has been on the rise, hitting $328.2 million in 2019. All signs point to that number growing, especially given the National Institutes of Health’s recent decision to award approximately $53 million in annual funding over the next five years to 10 research organizations in a continued effort to find a cure for HIV.

These numbers, however, primarily consist of funding tallies from the public sector and philanthropies — AVAC acknowledges that industry funding is missing from those totals.

In terms of cures in the pharma pipeline, there are currently less than a dozen specified ‘cures’ in early-stage trials, five of which fall within market leader Gilead’s pipeline. (TAG Pipeline report, PhRMA Medicines in Development report)

Mangat notes that because there are no approved cures for HIV and that “candidates tend to go in and out of the pipeline,” the cure market generally gets rolled into the treatment market for assessment purposes.

In reality, the line between treatment and cures has become increasingly blurred with the proliferation of functional cures, which essentially trigger a state of ‘HIV remission.’

“Because what we are mainly talking about at the moment are functional cures, some of the HIV treatment pipeline consists of potential therapies that could offer a cure as well,” says Mangat.

Klaus Orlinger, Hookipa Pharma’s executive vice president of research, says that, in his experience, the designation between a potential cure and treatment can’t be made until clinical trials begin, although there are generally preclinical indicators.

“Together with our partners, we did run preclinical studies that make us believe that our vector can make a significant difference in this patient population, but you cannot mimic the situation of HIV positive patients that have previously been on ART in a preclinical model. That has to be addressed in a phase one clinical trial,” says Orlinger.

Hookipa, together with partner Gilead, plans to use its proprietary technology to design arenavirus vector-based vaccines, as part of a functional cure for HIV. If Hookipa’s trial begins as anticipated in 2023, the company will join a small number of pharma companies with potential cures in the clinical pipeline.

AbbVie | phase 1: ABBV-1882 is a combination of AbbVie’s budigalimab, an anti-PD1 mAb and ABBV-382, an anti-a4b7 mAb, being investigated as a functional cure for HIV.

American Gene Technologies | phase 1: AGT103-T is a single dose autologous cell therapy currently being tested as a one-and-done HIV cure in the RePAIR trial.

MacroGenics, NIAID | phase 1: MacroGenics, under a contract awarded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, completed a phase 1 study evaluating MGD014, a bispecific dual-affinity re-targeting (DART) molecule, in persons with HIV maintained on ART. A phase 1 study of DART molecule MGD020 alone and combined with MGD014 will initiate in 2022, with the goal of both molecules becoming part of a strategy to reduce/eliminate latent HIV reservoirs.

Excision BioTherapeutics | phase 1/2: EBT-101 is a CRISPR-based therapeutic that utilizes an adeno-associated virus to deliver a one-time intravenous infusion intended to functionally cure HIV infections.

Gritstone Bio, Gilead Sciences | phase 1: Testing an HIV-specific therapeutic vaccine that uses Gritstone’s proprietary prime-boost vaccine platform, comprised of self-amplifying mRNA (SAM) and adenoviral vectors, with antigens developed by Gilead towards the end goal of a curative treatment for HIV.

Gilead Sciences | phase 1b: Elipovimab is a first-in-class effector-enhanced broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody (bNAb) being tested towards the goal of reducing or eliminating the HIV reservoir in patients.

Rockefeller University, Gilead Sciences | phase 2: Two investigational broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) – GS-5423 and GS-2872 – developed by Rockefeller University and licensed by Gilead are being evaluated for use in HIV cure strategies.

Gilead Sciences | phase 2: Lefitolimod, a toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9) agonist being investigated as part of a functional cure for HIV by Aarhus University Hospital in collaboration with Gilead

AELIX Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences | phase 2: The AELIX-003 trial is evaluating a regimen of Aelix’s HTI T-cell immunogen vaccine and Gilead’s vesatolimod, an oral toll-like receptor 7, towards the end goal of achieving a functional cure of HIV infection.

GeoVax | phase 1: In collaboration with researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, the GOVX-B01vaccine is being tested as part of a combinational therapy towards the end goal of achieving a functional cure of HIV infection.

ViiV Healthcare | phase 2: N6LS, ViiV’s broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb), is being tested in the HIV cure space.

Richard Jefferys, Basic Science, Vaccines and Cure Project director at Treatment Action Group (TAG), a community-based research and policy think tank, says the last decade has brought a greater rise to the prominence of cure research. Part of Jefferys’ role at TAG is to update the organization’s highly-cited listing of HIV cure-related clinical trials and studies.

TAG’s 2021 pipeline report, which catalogs clinical trials and observational studies related to the research effort to cure HIV, listed just over 130 active studies, 19 of which were recently launched. However, the bulk of these trials is sponsored by academia or the public sector, not the pharma industry.

But momentum in the pharma industry is picking up, with several more companies like Hookipa aiming to launch cure-related trials by 2023. Among them, major players Gilead and GSK/ViiV Healthcare. ViiV plans to take its host targeted IAP inhibitor into the clinic this year on the path to demonstrating that the molecule has utility as part of a cure regimen.

Merck, partnered with Boston-based startup Dewpoint Therapeutics, plans to leverage Dewpoint’s expertise in molecular condensates to develop an HIV drug candidate with a unique mechanism with the potential to cure HIV.

Los Angeles-based gene-modified cell therapy developer Enochian BioSciences says it also anticipates launching a trial of its potentially curative cell therapy treatment that combines analogous Natural Killer and Gamma Delta T-cells.

If any of these cures were to advance out of the clinic, Mangat says drugmakers will face a new set of market considerations. The durability of the cure will play a big role in the pricing structure, with one-off cures being priced the highest and functional cures priced according to how long they enable life without ART.

“There will be additional considerations in terms of the regulatory process and uptake. It will be quite different from ART, likely more towards what you’d expect for conventional gene and cell therapies,” says Mangat.

And, of course, if any company could find the holy grail of HIV treatment, the financial rewards would be considerable.

“Although it can look as if it counteracts the industry’s first aim of providing treatment to patients, if one of these companies did manage to find a cure for HIV, it would be very, very lucrative for them,” says Mangat.

Two goals, one stone

While leaders in the HIV treatment space express confidence about ending the epidemic by 2030, they also acknowledge that it’s a process — and one that lacks a silver bullet solution. Fortunately, this process is already well underway.

“The reality is that we have the tools to start moving toward the end of the HIV epidemic now,” says Smith.

The process is driven by a continued search for innovation, and that innovation has been found by looking to areas of unmet need among the patient population. Key to understanding these needs, and ultimately, solving the puzzle of both ending the epidemic and finding a cure, has been widescale collaboration.

“As we continue innovation to discover a cure for HIV and help bring an end to the HIV epidemic, our partnerships and collaborations are more important than ever,” says Plummer. “A multi-pronged approach will likely be needed to achieve the goal of curing HIV. We are working closely with industry, academic and community partners on preclinical and clinical studies and sharing insights from our cure research program that can benefit the entire scientific community.”

This sentiment is shared by ViiV as well.

“We realized a long time ago that we could go much further in our efforts if we worked to bring together the best and the brightest in industry and academia to focus on exploring every avenue, mechanism and compound towards our end goal of an HIV cure,” says Heather Madsen, Ph.D., head of Bioinformatics and HIV Cure at ViiV Healthcare.

ViiV boasts more than 50 active collaborations worldwide with pharma and biotech companies, government agencies, academic institutions and non-profits. It’s industry-academic partnership at

the UNC HIV Cure Center is the only one of its kind dedicated to finding a cure for HIV.

“[The partnership] combines the best of cutting-edge basic research with the drug discovery and development expertise of pharma and importantly, allows a focused and dedicated effort to accelerate towards a cure,” says Madsen.

Leaving no one behind

Perhaps in no other treatment area are socioeconomic disparities more pronounced than the HIV landscape. These disparities not only affect the goal of ending the HIV epidemic, but are also a driving force behind the search for a cure.

In the fight against HIV, many lower-income countries rely on support from humanitarian aid programs, such as those set up by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and UNAIDS. But questions about the long-term sustainability of such programs create ongoing uncertainty for people living with HIV in lower-income countries.

“There’s people right now around the world that worry about what would happen if PEPFAR ended. If a new American president decided that they didn’t want to keep supporting that program, suddenly millions of people around the world could have their treatment supply cut off. Part of the impetus for wanting to get to a cure is to eliminate those uncertainties hanging over patients,” says Jefferys.

Even in high-income countries, the financial burden of HIV treatment is significant. In the U.S., government spending on the domestic response to HIV has risen to more than $28 billion per year. A cure represents the future possibility of freeing up that spending for other diseases.

From the beginning of the HIV epidemic when activists took to the streets in New York City and stormed the FDA headquarters in Rockville, Maryland to protest, the voice of people living with HIV has been instrumental in inciting progress. Pharma companies in the HIV space have learned to listen to these voices, fine-tune their approaches and engage with the HIV community.

“Our mission is to leave no one living with HIV behind, and as a former physician on the frontlines of the epidemic for over 20 years, I am committed to this, because it ensures that our efforts stay directly grounded in the community of people living with and impacted by HIV,” says Smith.

Ultimately, regardless of the mathematical calculation used to reach the end of the epidemic, all people living with HIV are part of the equation.

“When someone living with HIV reads about ending the epidemic, it doesn’t really answer the question of when it’s going to end for them. That’s why it’s so important to acknowledge that ending the epidemic will require a cure,” says Jefferys.

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'