Designing a regulatory roadmap for psychedelics

Renaissance. Resurgence. Revitalization. No matter how one chooses to characterize it, this is an exciting time for neuropsychiatric research involving psychedelic compounds.

More than 80 organizations have publicly embarked on psychedelic drug development efforts recently. Regulatory bodies — including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Health Canada, and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) — have supported some of these efforts by allowing expedited drug development pathways.

The upsurge in interest is largely due to unprecedented mental health awareness sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic. As long-standing stigmas around mental health conditions have diminished, pleas have arisen for more efficacious treatments for depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and other neuropsychiatric diseases. Some psychedelic compounds suggest therapeutic promise, albeit mainly with limited initial safety and efficacy data in small proof-of-concept studies.

Although regulatory and funding agencies alike have shown more willingness to support psychedelic research, most psychedelic pharmaceuticals (with a few notable exceptions) are in the early stages of clinical exploration. The landscape is far from settled. However, it appears that regulatory agencies will continue to encourage more collaborative working relationships during psychedelic drug development — an advantage that sponsors, contract research organizations and other stakeholders should actively embrace.

Caution flags

As stewards of public health, the FDA and other regulatory agencies understand the drawbacks of current mental health therapies. They appreciate psychedelics’ potential but also acknowledge the substantial challenges and knowledge gaps that exist.

To begin with, these studies typically involve exposing vulnerable patient populations with difficult mental health diagnoses to altered states of consciousness. Furthermore, our collective understanding of psychedelics is limited despite generations of use by some Indigenous cultures. Their pharmacology is complex, and we do not fully understand their long-term and short-term safety profiles. Safety profiles in general are promising, but we know little about what predicts the adverse effects that do occur — and some are severe.

Even when psychedelics appear to yield positive outcomes, science doesn’t wholly comprehend the durability of their efficacy or whether a mystical experience is required to achieve positive effects. Some people describe the use of psychedelics as a highly profound, often spiritual, experience that evokes a sense of unity with the universe. Early data suggests that the more deeply patients have this experience, the better their clinical outcomes. Still, we have much to learn. We also have not definitively answered whether psychedelic drugs alone can provide optimal results, or whether concomitant psychotherapy is necessary.

In addition to the many clinical complexities involved, most psychedelics currently are Schedule I controlled substances with very strict legal and regulatory requirements. That means researchers typically must receive federal approval — as well as state approval in the U.S. — to study them.

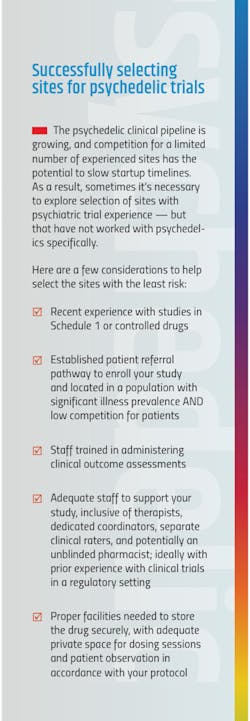

These restrictions are enforced not just by U.S. regulatory agencies, but internationally through constructs such as the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Every country has its own terminology, processes and complexities. Still, under the U.N. Convention, special licenses or authorizations are required to manufacture, trade, distribute or possess Schedule I drugs. Consequently, the number of sites experienced in running psychedelic clinical trials is quite limited (see sidebar).

Because many psychedelic compounds are difficult to import and export, not all drug distribution vendors will handle them. Sponsors, therefore, often try to simplify processes by conducting studies in the same region where the compounds are produced.

In most regions, sponsors must also ensure compliance with manufacturing standards. While the public often perceives psychedelics as ‘natural’ because some originate in nature, they generally need to be manipulated or otherwise manufactured. Even if the study drug arises in nature — such as mushrooms containing psilocybin — sponsors must meet strict chemistry, manufacturing and control (CMC) requirements. This is as much a strategic endeavor as it is a tactical one.

At heart, CMC entails a quality strategy that must be thoroughly planned with both scalability and the duration of the drug development journey in mind.

In the U.S., the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) establishes annual Aggregate Production Quotas (APQ) for Schedule I controlled substances. Those registered by the DEA to manufacture Schedule I controlled substances must file a quota application and receive approval. Interestingly, however, the DEA agreed to raise the manufacturing APQs for 2023 for some psychedelic compounds.

At the same time, moves to ease a few of the regulatory hurdles associated with psychedelic research have gained traction in Congress. The Breakthrough Therapies Act, a bipartisan bill, aims to give additional muscle to the FDA’s Breakthrough Therapy designation. If the legislation were to become law, Schedule I drugs that receive this designation could be reclassified by the DEA as less-restricted Schedule II drugs.

The landscape around psychedelic research is clearly shifting. While it’s exciting to ponder the potentially positive implications, the rapid pace of this evolution only compounds the sizable clinical and operational challenges intrinsic to psychedelic studies. Thus, many sponsors could benefit from guidance to maintain the rigor of regulatory-controlled research. Fortunately, regulatory agencies increasingly appear to be open to such collaboration.

Expedited pathways

Regulatory agencies require the same data and clinical trial processes for psychedelics as for any other drug in their intended therapeutic area. Still, some drug development programs may be eligible for expedited pathways.

For sponsors conducting studies in the U.S., the FDA offers four expedited pathways: Fast-Track designation, Breakthrough Therapy designation, Accelerated Approval and Priority Review. Each pathway has very clear criteria which must be met. As a rule, though, expedited pathways are intended for drugs designed to address unmet clinical needs and/or improve upon existing treatments for serious conditions.

None of these pathways are new. Fast Track was first implemented in 1988, Accelerated Approval and Priority Review were unveiled in 1992, and Breakthrough Therapy designation arrived in 2012. But recently, Breakthrough Therapy designation has been granted for several psychedelic studies.

Used for early-phase studies, the powerful Breakthrough Therapy designation speeds up drug development and review. Sponsors must provide evidence that the drug “…may have substantial improvement on at least one clinically significant endpoint over available therapy.” However, Breakthrough status imparts all the features of the Fast-Track pathway — including earlier and more frequent communications with the FDA — plus, it provides intensive FDA guidance involving senior FDA officials throughout the entire drug development journey.

Indeed, sponsors are strongly encouraged to engage regulatory agencies early in the process and work with them for the duration of development. Expedited pathways enable regulatory scientists to essentially become members of the development team, which can help sponsors alleviate costly and time-consuming oversights. For example, traditional CMC requirements might be difficult to comply with given a Breakthrough Therapy’s accelerated development timeframe. Yet early and collaborative conversations with regulators could help sponsors navigate potential CMC pitfalls.

Over the past few years, the FDA has approved the Breakthrough Therapy designation specifically for some psychedelic-assisted therapies. In 2017, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) was granted the designation for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. In 2018, COMPASS Pathways received it to study psilocybin-assisted therapy for treatment-resistant depression. In 2019, the designation was granted to the Usona Institute for its clinical trials of psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder.

Regulatory collaboration

Regulatory collaboration is a much-welcomed advantage that can deliver strategic benefits for sponsors and the patients they ultimately serve. It’s not an opportunity to be wasted.

Within each of the various expedited pathways are built-in occasions for regulatory discussions. For instance, sponsors usually request Fast Track designation at the investigational new drug stage, which enables early and ongoing communication with the FDA. During the drug development phase, sponsors can talk with the FDA about applying for Accelerated Approval; even when applying for drug approval, sponsors can request Priority Review.

In addition to these innate conversation points within the expedited pathways, sponsors should also seize upon invitations from regulatory agencies for early engagement meetings, continual development meetings, and pre-submission meetings.

Formal advice routes — such as scientific advice, for example — exist for products and/or studies. On occasion, sponsors may have the chance to receive parallel advice from the FDA and the Scientific Advice team at the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Speaking to appropriate national regulatory agencies and/or innovation offices may be another available option.

Sponsors should ensure that regulators have all the information they need to make informed decisions. Opportunities for collaborative discussions are not the time to curate what is shared. Moreover, in response to regulatory feedback, sponsors must be prepared to pivot. One of the biggest benefits of early collaboration with regulatory agencies is the chance to gain critical feedback that should not be ignored.

Ideally, sponsors should be open to defining and engaging all stakeholders in the drug development ecosystem. They should think about the different points in the drug development journey and recognize that collaborations sometimes require the involvement of multiple stakeholders. Then, to optimize their engagement with regulatory agencies, they should consider seeking the knowledge of either internal or external regulatory experts. A regulatory expert’s role is to help the wider team think strategically and carve out the optimal regulatory pathway feeding into the overall development journey. They are tasked with constantly assessing risks and changes, and helping stakeholders adapt and pivot as necessary.

In the current psychedelic research climate, no sponsor or stakeholder has to go it alone. Collaboration early and often could help shorten the drug development journey, saving both time and money and getting potential therapies to vulnerable patients faster.

The path forward

In recent years, psychedelic studies were primarily within the purview of academic institutions. Today, that dynamic is shifting as rapidly as the regulatory climate. Driven by an intense public focus on mental health, industry and academic researchers alike are ramping up their exploration of psychedelic therapies.

Still, the path forward is not easy. Clinical trials must be designed strategically, with the ability to change course as the regulatory landscape evolves. The learning curve can be steep for sponsors that are less experienced with psychedelic studies. Yet, with the right regulatory collaborations, sponsors can find opportunities to optimize their studies of this emerging therapeutic paradigm.