Editor's note: This article, which first appeared in the December issue of Pharma Manufacturing, was awarded an American Society of Business Publication Editors (ASBPE) National Gold Award. In addition, Meagan Parrish received the 2020 Stephen Barr Award — an award named for one of ASBPE's most honored journalists — for her work on this article.

“Much of what we will hear today will sound shocking, not only because of the scary state we find our drug supply in, but also because of how little attention it’s received — and it’s been years in the making,” Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) said in her opening remarks of a hearing this October for the Subcommittee on Health and the Committee on Energy and Commerce.

The focus of the hearing was on safeguarding the pharmaceutical supply chain and Janet Woodcock, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), was in the hot seat facing a Congressional panel.

A spate of recalls triggered by contaminated active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), many of which were produced overseas, wiped out a significant supply of heart medications in America this year — and Congress wanted answers.

What caused the contamination? How did we let these impurities slip into the American drug supply chain? How did U.S. manufacturers lose their foothold in the API market to so many companies overseas? How can the FDA get a better handle on the quality issues surrounding foreign-produced APIs — without causing disruptions to the supply of critical drugs?

In the midst of the questioning, Woodcock made an admission at odds with a top official charged with protecting the safety of American drugs.

“The generic drug supply is so fragile that the FDA has to make hard choices between enforcing quality at a plant and avoiding a drug shortage. Can you speak to this?” Eshoo asked Woodcock.

“Sometimes this is true — both for innovator and generic drugs,” Woodcock said, admitting that when quality issues at a plant arise, the agency often has to decide if patients can be without the treatment long enough for the agency to put remediation steps in place at the facility that would “render the product safe.” In other words, sometimes quantity has to come before quality.

Drug prices and shortages have drawn Congressional and consumer ire for years — putting pressure on the FDA to keep a healthy supply of much-needed low-cost drugs on the market. But the agency has been working against an inescapable truth of our free economy. Because many of these everyday generic drugs are sold at a low cost, it makes little financial sense to manufacture them in the often high-wage, high-tech environment of an American facility. Thus, the winds of economic incentives have blown production overseas — and farther away from the watchful eyes of the FDA.

It was really just a matter of time before a quality control issue came along and rocked the American pharma world.

“This is a crisis and today we will define it in depth,” Eshoo said. “Most importantly, we have to focus on solutions.”

The fallout from this year’s recalls of blood pressure treatments is still unfolding, and it’s unclear just how much the industry will pay for the debacle in lost product, regulatory fines and decreased patient confidence. But what is apparent is that API quality disruptions in far-away countries are creating a ripple effect through the supply chain that’s reverberating back to American manufacturers.

Now that the incident has brightened the spotlight on quality for all drug manufacturers and their suppliers, the industry and regulators have arrived at a new crossroads. Going forward, the question is how the FDA and American manufacturers can get control of quality throughout the global supply chain to avoid a massive recall mess all over again.

How we got here

“I’m going to be disparaging of drugs made in China and India,” Dr. David Gortler warned me at the start of our interview. Gortler was once an FDA official and has since held many noteworthy policy and consultant positions in Washington, D.C. — most recently with the consultancy firm, FormerFDA.

Our conversation began on an upbeat note about the FDA’s biggest wins in 2019, and Gortler complimented the agency on doing “a good job of removing the backlog of applications for generic drugs.” But the tone quickly changed when Gortler began detailing the downside of this accomplishment.

“While they’ve gotten rid of the backlog, we’ve become almost completely dependent on Chinese and Indian generic drugs,” he explained. “But they don’t meet quality standards. [Inspectors go to facilities there]…and find no running water, personnel running around barefoot, records kept in pencil, etc.”

The picture Gortler paints of the generic drug supply chain is, of course, much bleaker than the FDA’s perspective. According to the agency, the FDA’s standards for quality are among the highest in the world.

“FDA’s testing, going back to 2003, has found that only one percent of drug products analyzed deviated from acceptable standards,” the agency said in an emailed statement.

But when it comes to the APIs pouring into the American supply chain, the FDA’s grasp on the size and scope of quality issues only extends so far.

In a written testimony to Congress, Woodcock described how the landscape for lower-cost drug products, and particularly APIs, has evolved over the last few decades. Because the cost of doing business in China and India is so low with regards to labor, resources and regulatory controls, American and European countries can save an estimated 30-40 percent by outsourcing to these countries.

According to the agency, China and India API manufacturing facilities now account for about 13 and 18 percent (respectively) of all API facilities in the world. Although the number of facilities is not as high as those in the U.S. and the EU, the volume of APIs from those countries — and especially China — on the global market has been expanding rapidly.

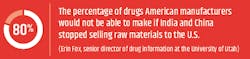

Woodcock stated in her testimony that the FDA is unable to track the real-time volume of APIs being sourced from countries like China, and is only able to retrospectively see what happened in annual reports. But Rosemary Gibson, a health care and patient safety expert at a bioethics nonprofit called The Hastings Center, and co-author of “China Rx: Exposing the Risks of America’s Dependence on China for Medicine,” has stated that China controls about 80 percent of the global API supply.

Although India, which has experienced a generic drug boom in the last decade, has received its fair share of negative attention for various quality issues, many of its generic finished dosage companies also source APIs from China, putting drugmakers there at the same risk of quality issues as those in the U.S.

When it comes to API quality issues, the common refrain is that “all roads lead to China.”

The consequences of poor quality APIs can be far-reaching as low-cost generics account for nearly 90 percent of all prescriptions in the U.S. The issue came to light in 2018 when traces of at least four impurities, including N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen, were found in common angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) medications such as valsartan. The findings triggered recalls of at least six generic versions of the medication in more than 20 countries. Because of the recalls, valsartan products, used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure, are now in shortage in the U. S. and prices for other formulations have shot up.

Since the ARB recalls, the FDA has been busy with inspecting facilities believed to be at the root of the problem and has issued a number of warning letters to companies in India and China. The agency’s most recent evaluations of the valsartan mess have pointed to manufacturing issues related to solvents, which are commonly used during the synthesis process in API manufacturing.

In an emailed statement, the FDA said “the nitrosamines found in ARBs may have been generated when specific chemicals and reaction conditions are present in the manufacturing process of the drug’s API, and may also result from the reuse of materials, such as solvents.”

In one November 2018 warning letter issued to Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceuticals located in Linhai, China, the FDA said that the company failed to adequately investigate and resolve manufacturing issues related to solvents after NDMA was detected in batches of valsartan API.

To be sure, recall events like the valsartan one are rare. To ensure quality, the FDA and the pharma industry have created layers of pre-market testing and post-market inspections meant to keep the drug supply safe. But, as the valsartan recalls show, it’s not a fool-proof system and there are several ways the industry and patients could be exposed to more troubles down the road.

When an FDA inspector comes knocking at the door of an American facility the rules are clear: The company must provide full access to its operations and records at a moment’s notice. Importantly, the agency doesn’t have to warn the company that it’s coming and if a company fails to comply, the consequences can be swift and severe. But overseas, the FDA often loses this critical element of surprise.

“If a foreign facility needs to be inspected…then our State Department has to get permission from that country’s State Department and they have to know everything about the inspector’s trip, and exactly what they are doing every hour of every day. That process can take six months,” Gortler explains. “By that time, foreign government officials can leak the information to the company [the FDA wants to inspect]. So, what you end up seeing is a ‘staged inspection.’ As soon as [the inspector leaves]…it’s back to monkey business.”

In her testimony to Congress, Woodcock admitted to this particular problem, but pointed out that inspections have increased in foreign facilities in the last few years. Under the Generic Drug User Fee Act, the FDA collects fees that have helped fund the number of foreign inspections and increase the total inspected from 993 in 2014 to 1,245 in fiscal year 2018.

Could more inspections alleviate quality woes? Even if they could, Woodcock said the FDA has struggled to find qualified inspectors to hire, making it challenging to cover more ground.

Also, when inspections target high-risk facilities only after a quality complaint, they can be a poor way of stopping an issue before it starts. This is where testing raw materials and finished products is supposed to come in.

Making the grade

The FDA selects dozens of finished dosages each year to test based on certain criteria including quality complaints or products that have been flagged for having a difficult manufacturing process. The agency also screens raw materials such as APIs being imported into the U.S. But according to Gortler and Lee Rosebush, a partner with the law firm BakerHostetler, the agency’s testing of these ingredients doesn’t go far enough.

“In a 2016 guidance document from the FDA, U.S. manufacturers of an API or finished product do not have to test every lot or batch that comes in for potency and purity,” Rosebush says.

Although Rosebush suggested that the FDA only requires impurity testing for every third or fourth batch that enters the U.S., Gortler says that the agency hardly ever requires tests of imports at all, and pointed out that if it does, the results are not made public.

“So if you [don’t have to test every batch], an issue can potentially slide through easily,” Rosebush says.

Instead, much of the quality control burden falls on the industry’s own auditing system.

“It’s on American companies to initiate the auditing process and see it through with due diligence,” explains Blaine Van Leuven, the CMC regulatory director of Clarivate Analytics, a research and analytical firm.

According to Van Leuven, when American manufacturers want to work with a foreign supplier, they will often send their own inspectors to qualify that company’s manufacturing process, and test APIs for potency, shelf life and impurities. Ideally, the process is ongoing and American companies audit their suppliers on a continual basis. Global regulatory bodies such as the FDA and European Medicines Agency also require this documentation to confirm product quality and compliance in order for drugs to be approved for sale on their markets. Ideally, American companies audit their suppliers on a continual basis. Yet, because of the cost of sending auditors overseas, Van Leuven says that some smaller American companies may opt to instead rely on communication and documentation from the supplier and confirmed internal test results.

Then, Van Leuven says that once the API supplier is deemed qualified, the focus shifts to testing finished drug products. Van Leuven admits, however, that testing for impurities in the finished product is not as specific as screening APIs.

“The reduced testing is kind of a loophole,” she says. “Testing a finished product for impurities is not as robust or as granular as when you’re testing APIs, because drug substance impurities are expected to be controlled and not increase during drug product manufacture.”

The quality fallout

Despite Eshoo’s call for solutions, it’s unclear what actions, if any, Congress plans to take on the issue of sourcing APIs from abroad.

In an emailed statement, the FDA said that the agency will stay “continually engaged” with lawmakers and that, “Generally speaking, FDA is encouraged by Congress’ continued interest in how we approach the complexities associated with greater API manufacturing.”

That doesn’t mean that the agency and industry haven’t been busy tackling the problem on their own.

Self-Yelp for pharma?

Earlier this year, the FDA’s Drug Shortages Task Force, which was created to determine the root causes of shortages and make recommendations for improvement, floated its first ideas to quell shortages. Among the three main solutions was a new system aimed at encouraging higher quality among American facilities, and thus alleviating shortages caused by manufacturing problems. The general idea is that pharma companies would publicly disclose their quality management system and rate their own performance.

“A rating system could be used to inform purchasers and even consumers about the state of, and commitment to, the quality management system maturity of the facility making the drugs they are buying,” the FDA stated.

So far, self-rating pharma plants is just one of several proposals, and there’s no word yet on when this kind of system would be up and running in the industry. To get it going, the agency said it will have to further engage with industry, academia and Congress.

Higher tech

During the hearing, several lawmakers grilled Woodcock about how the FDA can get more companies to produce APIs in America. The issue is complicated by the fact that the Chinese government has launched a deliberate initiative to boost its country’s pharma industry and sometimes financially supports its pharma companies.

“I think the horse has left the barn on this issue,” Van Leuven said when asking about re-shoring API production.

But Woodcock stuck to one potential solution — supporting advanced manufacturing technologies for American pharma companies. In an emailed statement, the FDA said that technologies such as continuous manufacturing and 3D printing can “improve drug quality, address drug shortages of medicines and speed time-to-market.”

“Advanced manufacturing technology, which FDA supports through its Enhanced Technology Program, has smaller facility footprint, lower environmental impact, and more efficient use of human resources than traditional technology,” the FDA said.

Increased transparency

When asked what the agency’s plans are for other forthcoming quality initiatives, the FDA didn’t mention increased pharma product labeling or more testing of API imports — but both are considerations that Gortler and Rosebush said should be on the agency’s radar.

“When you go to a pharmacy to purchase a drug, pharmacy labeling isn’t required to inform you where it’s sourced from,” Gortler says. “I think consumers would have serious misgivings about buying drugs from countries like India and China, which have had egregious quality control lapses.”

Gortler and Rosebush also both admonished the agency for not requiring testing for every lot of APIs coming in from overseas.

“Every batch without exception, especially from foreign facilities, should be tested, and prominently published for all to view,” Gortler says. “But there’s not even talk of it.”

“The fact that the FDA doesn’t require this testing scares me,” Rosebush says.

More recalls?

The valsartan recalls could be just the beginning. A report released earlier this year by Stericycle, a medical waste and compliance solutions firm, showed that although the number of pharmaceutical products recalled in Q2 of this year decreased, the total volume of drugs that were recalled shot up by about 86 percent over Q1. With more FDA eyes turning overseas, more recalls could be on the way.

“I think the scrutiny of the foreign supply chain will increase,” says Chris Harvey, the director of recall solutions at Stericycle. “So now I think there will be an increase in inspections in countries like China and India. Anytime there’s an increase in inspections, there are more opportunities to find more problems.”

Industry changes

Regardless of what the FDA requires, Van Leuven says that inside the industry, there’s going to be a “heightened awareness” now of quality issues related to foreign API suppliers.

“I think it’s a paradigm shift. Companies will start taking more responsibility instead of waiting until there’s a problem,” she says.

At Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, one of India’s biggest generic drugmakers, changes are already underway. Although Dr. Reddy’s wasn’t affected by the valsartan recall, the company was one of several who initiated a voluntary nationwide recall of its ranitidine medications in October due to confirmed contamination with NDMA.

According to Radha Iyer, vice president and head of Quality and Scientific Affairs for Global Developed Markets, Dr. Reddy’s has begun revamping its quality procedures in response to the ongoing NDMA scare. In addition to doing new risk assessments of their overseas API suppliers, Iyer says that Dr. Reddy’s has added new analytical methods designed to better detect nitrosamine impurities such as those found in valsartan. But Iyer says that companies like Dr. Reddy’s are starting to go beyond testing.

“We are using a much more holistic approach, which includes not just the technical perspective, but the overall management of quality,” she says. “We are reviewing and monitoring product performance as well as suppliers throughout our supply chain so we can secure end-to-end knowledge that will help us control quality problems.”

Van Leuven says that Clarivate also provides a platform called Newport that includes results of GMP inspections from global health authorities, which can be a useful tool for screening third-party manufacturers overseas.

Some pharma companies are also leveraging the potential rewards of China’s quality issues. In a recent press release about its forecast for growth in 2020, GVK Bio, a contract research and development organization based in India, stated that it is benefitting from a decreased interest in doing business in China.

“Over the past year, there has been an influx of interest from Western life sciences firms, looking to diversify their discovery and development services outside of China to mitigate risk. This is in part due to trade tensions, but also due to tightening regulations and safety-related plant closures in China,” the company stated. “The resulting disruption in the global supply chain, be it in discovery or development, has led to increasing interest in geographically diverse sourcing strategies.”

Iyer admits that the recent recalls will make it tougher for companies in India and China that are committed to high-quality manufacturing to maintain a good reputation in the industry.

“We have to learn from this and say, ‘What can we do differently?’” she says. “In my opinion [our bad reputation] is unreasonable and unwarranted. On the other hand, we have to think about why our reputation is declining.”

For American manufacturers, the emphasis on quality provides an opportunity to leverage high manufacturing standards and maybe, despite the challenges, bring some low-cost drug production back to the U.S. Either way, recent quality events have made one thing very clear — whether companies are manufacturing on U.S. soil or abroad, the issue of quality is going to stay top-of-mind for pharma and consumers.

“I think pharma quality is high as it is,” Van Leuven says. “But there are always going to be recalls, and then the rest of the industry is going to look to see how it can prevent this from happening again.”