They’re everywhere you look — pinkies intertwined on a playground, trusting handshakes, loving vows.

Most, if not all, of our collaborative efforts and therefore most of our major successes as a species have come to fruition because of the promises we make to one another.

While we may not think much of them at first, each kept promise throughout history has acted as a brick of trust in the greater relationship we have built as humans. Just the same, broken promises are behind some of the most painful experiences known, from heartbreak to war.

Within pharma, there’s a new promise on the horizon: a world without disease made possible through cell and gene therapies (CGT). Through the power of editing the minute and complex biological mechanisms that are to blame for things going wrong in our bodies, scientists dream of using CGT to eradicate diseases.

But harnessing the power of our cells and genes to potentially cure disease is the ambitious endgame in a long, complex process. Beginning to embrace the age of personalized medicine will require that biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes meet demand — and CGT is in demand like never before.

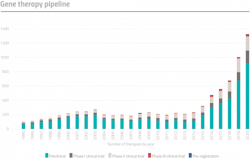

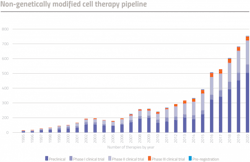

The drugs aren’t necessarily built on new technologies, but their exponential growth, catalyzed by the first Food and Drug Administration CAR-T cell therapy approval in 2017, has launched these therapies into a stardom state. Currently, there are 3,579 cell and gene therapies in development, and over 1,000 clinical trials are underway, which could result in the industry having as many as 10 to 20 new therapies approved every year starting in 2025.

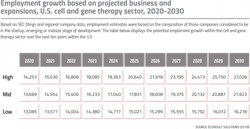

But while the demand for these life-changing drugs is skyrocketing, the industry is facing a rampant workforce shortage which, if not rectified, stands to derail the promise of CGT. If cell and gene therapies continue to grow as projected, the industry will need a steady supply of well-trained experts ready to manufacture tomorrow’s therapies.

Fulfilling the promise of a world where previously unmet disease states might now be able to be treated requires all the brains and hands the industry can find. And for CGT, moving through the ‘talent crisis’ will call for a change in perspective of what experts look like, how workers are trained, and an urgency to cultivate the talent ecosystem of the future — one that is capable of meeting the demands of a booming industry.

Harnessing cells’ powers

The U.S. FDA encompasses cell therapies to include drugs such as cancer vaccines, cellular immunotherapies, and other types of both autologous and allogeneic cells for certain therapeutic indications, like stem cells.

Gene therapy intends to manipulate the expression of our genetic instructions or change biological mechanisms in cells to treat disorders or prevent disease altogether. Within the scope of gene therapies, the FDA lists plasmid DNA, viral vectors, bacterial vectors, human gene-editing technology, and patient-derived cell gene therapy products.

While these therapies might seem new, cell and gene therapies have been around for a while. Cell therapies can be dated back to the ‘40s when the first bone marrow transplant was givento a patient with aplastic anemia. And while gene therapies didn’t pop onto the scene until later, scientists dosed the first patient with a genetic therapy back in 1990 — a 4-year-old girl who suffered from severe combined immunodeficiency.

Despite the technology having decades of research to support its potential success, it seemed that initial momentum stalled. While exciting, the risks seemed too high for patients.

Things changed in 2017 when the FDA approved the first genetic therapy, Novartis’ Kymriah, a CAR T-cell therapy used to treat certain pediatric and young adult patients with a form of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

“Everything changed when the FDA granted the first approval. Suddenly that told the world that cell and gene therapies can be used to treat diseases in a different way,” says Catarina Flyborg, vice president of Gene and Cell Therapies at Cytiva, a biotechnology company focused in advancing and accelerating future therapeutics.

Up until that point, Flyborg adds, the main challenges for CGT had to do with the unknown safety profile of therapies, as well as funding and public perception. Now the industry is tackling a different beast.

“Most things done thus far have been to address the symptoms. But here we have a life-changing technology and the number one challenge is that we don’t have enough people to produce it,” says Flyborg.

Staffing a promise

While it’s easy to blame COVID-19 for everything, experts believe that the pandemic did in fact cause a major disruption in the American labor force — and the numbers add up.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce estimates that since 2020, the labor force participation rate is 62.4%, down from 63.3% in January 2020. In 2021, more than 47 million workers quit their jobs, citing a search for improved work-life balance and flexibility, increased compensation and strong company culture.2

The same report outlined that labor participation is different across all industries; some have a shortage of labor, while others have a surplus. In the cell and gene therapy sector, economic growth has made the labor shortage more apparent, creating a deep need for skilled workers to meet the current demands.

“The economic success of our industry has amplified the need for skilled workers,” explains John Balchunas, who currently serves as the workforce director at the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL).

At NIIMBL, Balchunas provides strategic direction regarding the education and workforce and talent development activities for the public-private partnership dedicated to advancing biopharmaceutical manufacturing innovation and workforce development. He says that the conversation surrounding the workforce shortage has become more and more frequent, and companies are starting to realize that addressing the problem is mission critical.

Scott Gottesman, vice president of Human Resources at Avrobio, adds that from his perspective, CGT’s success can be considered a double-edged sword. “We are headed toward a seismic change in how much more talent you need in the industry,” he says. “If you’re more successful at advancing some of those trials and if we have a labor shortage, where’s the talent going to come from? How do we acquire it?”

According to the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, there are more than 1000 cell and gene therapy developers in the world, with more than half of them based in the U.S. Econsult Solutions projected the U.S. cell and gene therapy sector could potentially employ more than 32,000 workers in commercialization and R&D by 2025.3 But this hinges on being able to find enough qualified labor to fill these positions.

While drug manufacturing is always a resource-intensive endeavor, manufacturing cell and gene therapies requires specialized knowledge. Due to the nature of these products, companies who produce them are hands-on in both upstream and downstream processing.3 Cell and gene therapy products, especially those made using an autologous procedure, must be closely followed through the manufacturing process, beginning with the material collection, and ending when the treatment reaches the patient.

So while other biopharma products allow companies to use conventional channels to distribute drugs, cell and gene therapies must be delicately hand-held through the pipeline — but currently, there aren’t enough hands.

“It’s just too much demand for the supply that already exists and might exist in the future. So we see a significant talent gaptoday that we’re all quite worried about,” Gottesman says.

This labor gap Gottesman and Balchunas speak of is not limited to CGT, as the U.S. commerce report states that there are 11.5 million jobs in the U.S., and only 5.9 million unemployed workers. If every unemployed person in the country found a job, we would still have nearly 5.6 million open jobs.

To make matters slightly more complicated, within biopharma, and specifically within CGT, the need is not just for workers, but for specialized,highly skilled talent. “It’s taken decades to get the ‘cutting edge science’ to commercially available products, but now that CGT drugs are further down in the pipeline, we see a spike in the number of companies in this space and a drastic need for specialized or unique talent,” Gottesman adds.

In some ways, the CGT talent shortage can be considered the result of a positive phenomenon, one in which the industry is flourishing with the promise of new products and new cures. But who is going to fulfill that promise if there aren’t enough workers?

The bottleneck equation

While it is true that many industries are facing the same issue, when it comes to CGT, the stakes are high. In some cases, it’s literally life or death. It’s the patients who end up taking the brunt of the shortage, which is why there must be urgency in addressing the labor crisis.

“Our priority must be to get the treatments to everyone who needs them, and without having enough workers this becomes quite challenging,” says Flyborg.

Many patients receiving these products are severely ill, and time is not a renewable resource. Not having enough workers to manufacture these products creates a bottleneck that most patients can’t afford to wait through.

For example, one area of gene therapy that has generated excitement among patients and providers alike is CAR-T, an immunotherapeutic approach to treating blood cancers. In these therapies, T-cells are taken from the patient’s blood and are altered in a lab by adding a gene for a receptor (called a chimeric antigen receptor or CAR), which helps immune cells, T-cells, to attach to a specific cancer cell antigen. Then, the altered CAR-T is given back to the patient.

This process, known as vein-to-vein time, can take up to three weeks. But some patients don’t have three weeks, and some clinicians have noticed further delays in the manufacturing processes for these products.

Another concerning numeric relationship within the bottleneck equation is that there are currently six CAR T-cell therapies approved by the FDA for cancers such as lymphomas, some forms of leukemia, and, most recently, multiple myeloma. But every year, approximately 178,520 patients are diagnosed with these types of cancer.

And while there are roughly 70 cancer centers across the U.S. that can prescribe CAR-T, these lifesaving treatments are only available to a very small percentage of patients. Sometimes these centers have as little as 1 to 2 slots per month.

Flyborg emphasizes that the talent shortage is a contributing factor. “There aren’t enough people to scale up the products, which creates a delay in patients getting the treatment.”

Growing experts

There probably isn’t anything that incentivizes problem-solving more than when lives are on the line. According to Balchunas, solving the talent crisis needs to become an industry-wide priority.

“The industry really needs to start embracing new ways of demonstrating experience,” Balchunas says. “While approaches such as credentialing, apprenticeship and two-year technician training programs are slowly being embraced in our industry, widespread adoption requires more intentional buy-in from hiring managers.”

From a talent acquisition standpoint, Gottesman adds that the shift has begun. “We’ve seen a shift in perspective, from a traditional academic standpoint. Historically scientists would need to have a Ph.D. We don’t see that in our space anymore.” Now, he says, hiring managers are re-examining what traditional models, qualifications and titles determine expertise.

The industry is realizing that experts are not born, they’re made.

Organizations like NIIMBL, for example, have a track record of successfully catalyzing the development of new education, training, and professional development opportunities for workers coming from all experience levels including retraining and courses and skills development for those new to the industry. NIIMBL’s academic and non-profit member community itself is home to most of the world’s leading centers for specialized biomanufacturing

training.

Even companies themselves have started to create programs and allot resources for the cultivation and education of a new cohort of experts. Beyond hiring, companies like Avrobio and Cytiva are focused on fostering an internal talent ecosystem.

“Creating a self-sustained talent ecosystem where companies have their own educational system and develop their own talent becomes very important,” Gottesman says. “Having knowledge cross-pollination empowers companies and workers.”

Accelerating change

We all want to believe that fulfilling the promise of a world without disease as we know it is ultimately possible. But unlike other industries, the CGT labor shortage can’t be ‘fixed’ by any one silver technology bullet — the industry simply needs more humans.

“Although automation helps reduce wait time for patients, we still need more humans doing the science, having a relationship with the technology, and driving innovation,” says Flyborg.

Unfortunately, another thing that is needed is what many patients don’t have: time. “When you look at workforce development and talent development, generally, it’s a slow change endeavor. You’re not going to change it overnight,” Balchunas says. “You’re really talking about changing the mind of every hiring manager, every recruiter who’s out there so that they’re looking at different populations and different backgrounds to hire outside of their comfort level.”

When companies take control of the education of their workers, experts can go from being difficult to find to everywhere you look. “As we look at the future, the more you can shape or control a self-sustained ecosystem of talent, likely those companies will succeed more,” Gottesman says.

This ecosystem of industry talent ultimately impacts the larger ecosystem of our society. “I hope in 10 years, researchers, biotechs and pharmaceutical companies will have accelerated the development and commercialization enough so these therapeutics are available to anyone who needs them. Making these life-changing, and for some, lifesaving therapeutics accessible will change lives and our entire society and our global health care ecosystem will benefit,” says Flyborg.