When the news broke in March 2019 that Biogen, a biopharma titan, was abandoning development for a drug targeting Alzheimer’s disease, the reaction was one of predictable disappointment — but not surprise. Another heart-sinking data readout. Another blow to millions of Alzheimer’s patients. Another company’s fortunes sunk by a single press release. Another day in Alzheimer’s drug development.

Although failure is the norm in pharma, for no other indication is that fact quite as harsh as it is with Alzheimer’s disease where the common calculation is that 99 percent of drugs tested ultimately falter.

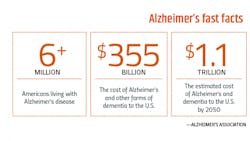

And perhaps for no other indication are the stakes quite as high. To date, no disease-modifying drug has ever been approved to treat Alzheimer’s, leaving patients with only a handful of medications to potentially alleviate symptoms. If just one could be shown to arrest the slowly advancing disease that robs patients of their cognitive functions and independence, the potential payoff for the company holding that holy grail would be astronomical.

“A new Alzheimer’s treatment would easily become a blockbuster,” says Pamela Spicer, senior analyst at Informa Pharma Intelligence. “The market is wide open.”

But although Biogen had decided to halt two late-stage trials of its drug, aducanumab, after a futility analysis concluded it was unlikely to provide benefit, the company didn’t toss the data into the dumpster fire. Instead, Biogen hunkered down, reevaluating its results and ultimately coming to a startling conclusion: The March analysis had been wrong, and one of the studies had trended in the right direction.

That October, in a move that sent shockwaves through the pharma world, Biogen announced that it would in fact file for approval of aducanumab with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) — a decision that could tee up the first new drug approval for Alzheimer’s in 18 years.

Confusion, controversy and conflicting beliefs have been swirling around the drug ever since.

Is aducanumab actually effective enough to warrant an FDA approval? Does it finally prove that drugs that help clear amyloid plaques in the brain slow the progression of Alzheimer’s?

Or would a regulatory approval offer false hope to millions of Alzheimer’s patients? And is Biogen, whose financial future is strongly tied to the drug, collaborating too closely with regulators to push through an OK?

Throughout the roller coaster ride aducanumab has since taken, critics and advocates have sprung up on both sides and remained sharply divided.

This June, the FDA is scheduled to finally render a verdict on aducanumab — a decision with major ramifications for patients, the industry’s wider pipeline for Alzheimer’s treatments, Biogen, and the science behind the drug. And as the June action date nears, the agency is navigating a complicated maze towards what will be one of its most consequential decisions of the decade.

Looming amyloid

Rooted within the debate about aducanumab is the idea that Alzheimer’s is linked to the build-up of beta-amyloid, a sticky protein that can collect in plaques in the brain along with tangles of tau, another protein that’s involved in transporting nutrients within nerve cells. What is known is that when beta-amyloid and tau clump up in patients with Alzheimer’s, it can trigger a cascade of brain cell degeneration and death, and ultimately, the hallmark symptoms of dementia.

What isn’t agreed upon is whether or not decreasing the amount of amyloid or tau can slow or reverse this progression of neuron destruction. Yet, for more than two decades, that idea — known as the “amyloid hypothesis“— has dominated Alzheimer’s drug research. And ultimately, the approach has led several major pharma companies including AstraZeneca, Roche and Pfizer, to drive head-first into an R&D ditch. The problem? Multiple drugs have been shown to help clear the brain of amyloid but haven’t improved clinical dementia symptoms.

It’s a situation that led one researcher to notoriously quip that by the time drugs clear amyloid, it’s too late, and the process is like removing tombstones from a graveyard — it won’t make the people buried there “any less dead.”

“Everyone thought that if you stopped these plaques, you could reverse Alzheimer’s,” says John LaMattina, the former president of Global Research and Development at Pfizer and the author of several books on the pharma industry. “But this is a great lesson in what can go wrong in drug development.”

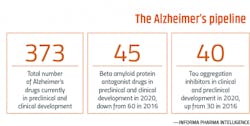

Although the amyloid theory is now teetering on the edge of a scientific cliff — many believe that drugmakers should abandon the target all together — today’s pipeline for Alzheimer’s is still filled with drugs targeting amyloid in different ways and, increasingly, tau. However, researchers are also fine-tuning their approach to amyloid while casting a wider net towards other targets.

“Right now there are over 120 Alzheimer’s drugs in clinical development and for the first time, over half are non-amyloid and non-tau drugs,” explains Dr. Howard Fillit, a neurologist and the founding executive director and chief scientific officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), an organization that helps fund Alzheimer’s drug development.

While some of the non-amyloid and non-tau drugs are aimed at new approaches to stopping Alzheimer’s disease, such as epigenetics, neuroinflammation and neuroprotection, Fillit says about half of the pipeline is devoted to testing repurposed drugs for Parkinson’s, hypertension, diabetes and more.

“We are trying to advance the field by taking risks on these repurposed drugs because we know the mechanism of action and there’s good evidence that they might be neuroprotective,” he says.

Yet, for those still in the amyloid game, such as Biogen, the goal has been to improve the odds of their drug’s success.

“All of these lessons have kept amyloid at the forefront because it is a hallmark of the disease, so it makes sense as a target,” Spicer says. “Despite the failures, pharma companies have learned and have refined their approach.”

Specifically, pharma companies have shifted to trialing amyloid drugs earlier in the disease progression — an approach they’ve been able to achieve thanks to the development of positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, which can reveal the presence of amyloid and tau long before a patient begins exhibiting symptoms. PET imaging, in fact, came into play in a big way during Biogen’s trials of aducanumab.

“It was a revolutionary aspect of the aducanumab studies because it was one of the first times everyone in the trial was proven to have Alzheimer’s through a biomarker test,” Fillit says. “Then the same PET amyloid test was used to test pharmacological efficacy by seeing the removal of amyloid plaques as measured by the scan. So this has become the first real rigorous tests of the beta-amyloid hypothesis.”

“Even though the amyloid approach is controversial,” Spicer says, “as we’ve seen [with aducanumab]…it’s on the cusp of potentially paying off.”

All those in favor

“Of the two studies … 302 was a positive study. We can’t argue about that,” Dr. Alireza Atri, a neurologist and the director of Banner Sun Health Research Institute, said during his introductory comments for a recent webinar Biogen gave on the results of its two late-stage studies of aducanumab.

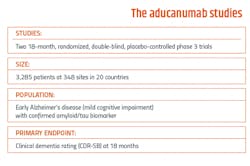

Organized by Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), the presentation by Samantha Budd Haeberlein, the head of Biogen’s Neurodegeneration Development Unit, was used to walk the audience through the results of its two key trials — dubbed ENGAGE (aka 301) and EMERGE (302).

There’s no doubting the scans. In patients with amyloid and tau present, brain scans using PET imaging are lit up in red and yellow where the plaques are growing. But follow-up scans from one year later of some of the nearly 3,300 patients involved in the studies revealed how those colors had faded as the amyloid cleared.

What’s more, Haeberlein said that patients given a high dose of aducanumab (10 mg) in study 302 showed improvement on their Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores, a global tool used in Alzheimer’s patients that measures memory, orientation, judgement and problem solving, personal care and more. When compared to a placebo, Haeberlein said patients on the high dose regimen of aducanumab fared 22 percent better on their CDR scores, while the lower-dose group had an intermediate effect of 15 percent.

Patients on the high dose of aducanumab in 302 also showed an 87 percent reduction in the clinical decline of neuropsychiatric scores that measure depression, anxiety and more. Caregivers of patients on the high dose also reported 84 percent less burden compared to caregivers of patients on a placebo.

There’s a caveat though — patients in 301 did not show the same level of improvement. Why the difference?

When patients in 301 had the opportunity for full dosing, Haeberlein said the results were similar to the positive outcomes observed in 302. She also pointed to a small group of patients with a rapidly progressing form of the disease who may have skewed the result.

In a recent interview, Atri spelled out why he believes that, despite the diverging results from 301 and 302, the bottom line is that the drug works to some degree.

“The data, though complex, is really clear and very consistent in critical respects,” he says. “The drug clears amyloid from the brain on average, and on a group level, there is a correlation between washing it out and having slower cognitive decline. When you look at CDR, the results are positive. Daily function? Same thing. Behavior? Same thing. We have all these different components we measure and they all went in the same direction.”

As for the futility analysis that caused Biogen to halt the late-stage trials in March 2019 because it predicted that they would not meet their primary endpoints? According to an update on aducanumab given by Biogen in October 2019, the analysis was flawed because it only considered patients who enrolled in the studies early and were not exposed to a higher dose for a long enough period of time.

Atri also says that aducanumab was a “victim of a miscalculation and a flawed futility analysis.”

Ultimately, Biogen has argued, the “totality of these data support a regulatory filing.”

Yet, Atri cautions that if approved, guardrails will have to be put into place when administering aducanumab. Although the safety profile of aducanumab is generally favorable, it can cause a potentially dangerous side-effect called amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).

“ARIA could potentially lead to hemorrhage or strokes if left unchecked,” he explains. “So in a real-world setting you don’t want an untrained doctor to select, infuse and manage a patient, and then that patient develops ARIA. We’ll need a lot of education, including for neuro-radiologists, to detect ARIA.”

Atri also admits that aducanumab shouldn’t be overhyped and that it’s not a cure. Additionally, there are several key questions hovering over the drug, such as whom the drug works best for, what dose is best and what other side effects could develop from long-term use. It is also still unclear what exactly the 22 percent improvement in CDR could mean for patients in the long-run.

“Theoretically, if you have 22 percent less decline over a year and a half, you’re going to have the equivalent of about four months additional benefit over that 18 month period,” Atri explains. “But if someone is diagnosed early, they may have 10-15 years of life left and a 20-25 percent slowing of disease progression could mean two to three years of additional benefit.

“We’ll learn more about that over time, which is probably going to take a decade,” he says.

Even with those lingering questions, major patient groups are pushing for approval.

“Advocacy groups are screaming for this drug,” Spicer says. “Right now, it is their only hope. Otherwise, there are only drugs that mask symptoms.”

But the mismatched results from 301 and 302 make it difficult to justify approving aducanumab. So groups like the Alzheimer’s Association have reasoned that instead of denying the drug, a good compromise by the FDA would be to offer a conditional approval that mandates a follow-up study.

Atri also argues that because of the large unmet need hanging in the balance, Alzheimer’s patients shouldn’t have to wait for Biogen to conduct another study before an approval is given.

“Are we really going to make people wait another five years for this?” he says. “I don’t think that’s right. People should have the choice to make an informed decision and have appropriate access to this.”

All those opposed

Ideally, data is meant to provide crisp, irrefutable evidence to help scientists avoid subjective interpretations. But as the situation with aducanumab shows, circumstances surrounding data can sometimes muddy what should be a clear-cut picture.

To some extent, the debate about aducanumab has been less about what Biogen presented — and more about how Biogen has made those presentations.

These concerns came to light on Nov. 6, 2020, when the FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee held a public meeting to vote on whether or not aducanumab should win approval. Minutes into the virtual meeting, it was clear that the feedback from the 11 scientists pooled to offer opinions on the aducanumab studies was not only going to be disapproving — it was going to be scathing opposition.

Right out of the gate, committee members took issue with a briefing document that the FDA put together ahead of the meeting. Rather than presenting its own separate information, committee members called out the FDA for taking the extraordinary step of collaborating with Biogen on a single document instead.

“Usually there is a sponsor’s briefing book and then a separate one from the FDA,” Dr. Scott Emerson, an emeritus professor of biostatistics at the University of Washington who served on the advisory committee, says. “But this one merged them.”

After learning that Biogen co-authored the FDA’s pre-meeting briefing document, Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy group known for not pulling punches with pharma, sent a letter to the agency’s Office of Inspector General demanding an investigation.

“We’ve been looking at pre-briefing documents for 20 years and have never seen anything like this,” says Michael Carome, the director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group. “This is what can go wrong with the FDA — the agency can be too biased with the industry’s interest. That can result in drugs coming to market that are not shown to be safe.”

Although Emerson, who has been serving on FDA advisory committees for about 20 years, says this wasn’t the first time he had seen a merged briefing document, he admonished the FDA clinical reviewers for presenting information on aducanumab that was “abnormally imbalanced” in its support for the drug.

“They didn’t present results — just conclusions,” he says.

The committee also expressed concerns about how many members of the FDA and Biogen have sought to explain away the negative results from the 301 study by focusing on the positive trends in 302. Emerson likened Biogen’s analysis to the Texas “sharp shooter fallacy,” a reference to a marksman who fires a shotgun at a barn and then draws circles around the bullet holes.

Caleb Alexander, a professor of epidemiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who also sat on the advisory committee for aducanumab, offered his own colorful take on why the FDA’s glowing support for aducanumab didn’t jive with Biogen’s data.

“It just seems to me like the audio and video on the TV are out of sync,” Alexander said during the committee meeting. “There are literally a dozen different red threads that suggest concerns about the consistency of evidence.”

Typically, the gold standard for winning approval from the FDA is two positive late-stage trials. And even if the FDA were to consider data from a single phase 3 trial, as it sometimes does, Emerson and others on the committee argued that the positive results from 302 alone are not robust enough to warrant approval.

When asked if 302 should be used as a benchmark to support FDA approval, the feelings of the committee were clear — 10 voted “no,” while one voted “uncertain.”

“This did not rise to the level of approval on a single pivotal trial and there were too many issues that were questionable,” Emerson says.

According to Emerson, Biogen took a number of other missteps on its path to seeking approval. The company, he says, rushed into the phase 3 trials, did not do a good job modifying the design of the studies, and because of the side effects associated with ARIA, many believe that the trials could not have been truly blinded. But most suspiciously, Emerson says that Biogen has yet to publish its results in a peer-reviewed journal.

“In this case, the peer-reviewed process would have made their presentation better,” he says. “Without that, I worry that they are trying to suppress the correct result.”

When asked if his opinion on aducanumab has changed in the months since the advisory committee meeting, Emerson is unequivocal: His concerns about aducanumab’s effectiveness have only gotten stronger. In fact, after digging through the available literature from the long list of other amyloid-targeting drugs that failed, Emerson came away with the conclusion that Biogen likely doesn’t have a positive study at all. Instead, Emerson believes Biogen generated the kind of “false positive” result that can happen from years of repeating similar studies.

“The more trials you do, eventually you find one that’s positive,” Emerson says. “But sooner or later we probably need to say that amyloid’s not the problem, because it is only a sign of the disease and not necessarily the root cause of cognitive decline.”

The FDA under pressure

In theory, FDA advisory committees are designed to provide the agency with scientific input from a group of outside experts. But according to David Gortler, who served as senior advisor to the FDA commissioner and was a member of the senior executive leadership team under former Commissioner Stephen Hahn, advisory committees typically back up the agency for decisions that have already been made.

“The FDA is looking for someone to validate what they already know,” Gortler says.

So what happens when the committee throws a curve ball at the FDA and votes against a drug the agency supports? Although the committee’s vote is non-binding — the FDA is not required to follow its advice — the agency usually does. Making any other move is certain to raise eyebrows.

“The agency could have denied approval by now but instead they received more data and analysis that would not have been available to the advisory committee,” Spicer says. “And the additional requested time may be a signal that they could go through with approval.”

Either way, the agency is undoubtedly moving carefully towards its final decision and there are several emerging factors that could come into play as the deadline nears. Chief among them is the lingering question of who will become the FDA’s permanent acting commissioner.

After the Biden administration took over in January, Hahn left his top spot at the agency and was quickly replaced by Janet Woodcock, the director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), who is now acting as the interim commissioner.

In a recent op-ed penned for Forbes, LaMattina wrote that Biogen has the most at stake when it comes to the impact of Biden’s final pick for commissioner.

Woodcock, who has worked at the FDA since 1986 and who Gortler calls a “landmark” figure with a “huge presence,” is the clear front-runner. Her storied history at the agency also offers insights into how she might view the aducanumab decision.

In particular, many have pointed to her decision in 2016 to support eteplirsen, a drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a rare and deadly condition that primarily impacts young boys. The drug barely performed better than a placebo in trials and the FDA’s advisory committee voted against approval. But with a chorus of patient groups demanding help, the FDA made the controversial call to give it the green light.

“[Woodcock] tends to be sympathetic to approving new drugs where there is tremendous medical need, but where the efficacy is not fully demonstrated,” LaMattina wrote in Forbes.

The decision-making mindset of the other candidate under consideration — Dr. Joshua Sharfstein — might be a little harder to predict.

According to LaMattina, Sharfstein, a vice dean at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who held a top position at the FDA under President Barack Obama, might be more concerned with maintaining public trust in the agency than appeasing patient groups.

“He is thought of as someone who would be tougher on the biopharmaceutical industry, particularly on the need for greater transparency with respect to the interactions that the FDA has with companies,” LaMattina wrote.

The Biden administration’s delay in naming a new FDA chief has left the door open for more public debate about the matter. Most recently, Woodcock critics have emerged among Democrats in the Senate, who accuse her of not doing enough to combat the opioid epidemic.

Now, reports have surfaced that the Biden team is looking beyond Woodcock or Sharfstein for the job. Either way, once the incoming chief is seated, there’s a good chance that person could have the final say about aducanumab.

“The approval process inside the FDA depends on the drug. Many will weigh in on the decision,” Gortler explains. “And if the drug fails down the line with one medical officer, someone else could appeal it up the chain. But the commissioner will have the ultimate authority.”

The conundrum for the incoming commissioner could not be much worse. No matter which way the agency sides, the decision will kick up a firestorm of backlash, either from patient groups who want the drug approved or from watchdogs who think the agency is too cozy with Biogen and want it rejected.

“It’s a no-win situation for the FDA,” LaMattina says.

Bracing for the fallout

Whatever fate awaits aducanumab, the FDA’s decision is going to impact a number of stakeholders. Here’s what the final word means for industry players.

Biogen

The exact estimates of how much revenue aducanumab could bring in vary, but its status as a sure-fire blockbuster is not in question. On the low end, analysts have predicted that its sales could reach $5 billion a year — others shoot as high as $34 billion, a number that would easily breeze past Humira, the world’s top-selling drug that is expected to rake in $20 billion this year.

For Biogen, who has been developing the drug with Japan’s Eisai, aducanumab would be a giant springboard out of its growing sales slump. Wall Street analysts believe that if aducanumab wins approval, Biogen’s shares could soar by 70 percent. But if not? The sales hole the company is already struggling with is likely to get much deeper.

Tecfidera, Biogen’s top seller, is now competing with a generic that hit the market last spring. Analysts predict that the new competition will cleave close to $3 billion off of Tecfidera’s sales this year, which pulled in $4.4 billion in 2019 and comprised 31 percent of the company’s total sales. Meanwhile, the company is also in a rut with Rituxan, a blockbuster autoimmune and cancer treatment, which is facing biosimilar competition and Biogen says will experience “significant erosion” this year.

All told, Biogen’s revenue slid by about 6 percent in 2020 to $13.45 billion.

Clearly, the company needs a boost and is counting on aducanumab to breathe new life into its financial forecasts. According to a recent Biogen earnings call, the company is planning to drop $600 million on launching aducanumab this year and has already allocated a “significant portion of its manufacturing capacity” to the drug.

The Alzheimer’s pipeline

According to Fillit, approving aducanumab would signal to drug developers and investors that amyloid-targeting drugs are worth the gamble.

“A lot of big companies have dropped neurosciences,” Fillit says. “But I think once we get some proof of concepts out there and if aducanumab is approved, I think you’ll see more interest in neurosciences in general, but in particular with Alzheimer’s disease.”

Aducanumab’s fate could also become entangled with an amyloid-clearing drug called donanemab being developed by Eli Lilly and Co. In January, Lilly reported positive top line results from a phase 2 trial that showed donanemab slowed decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale by 32 percent compared to a placebo. The potential success of another amyloid drug could give the FDA more scientific justification for approving aducanumab.

But because these successes in efficacy are still modest, others argue that an aducanumab approval could continue to focus too much R&D on amyloid — potentially steering investment dollars away from better treatments.

Atri, however, waves those concerns away.

“I think it’s a false argument that approving aducanumab will somehow stop the field from advancing,” Atri says. “It would be a first-generation drug…but later we’ll have second generation drugs that work better and may have less potential for side effects, just like we’ve seen with other drug classes for other indications.”

The FDA’s bar for success

What will the FDA’s ruling on aducanumab say about how it measures success with Alzheimer’s treatments?

According to Spicer, approving aducanumab could signal to the industry that the agency is willing to wave through a drug with lower efficacy.

“What happens with aducanumab could raise or lower the bar for regulatory approval,” Spicer says.

Biogen has also filed for approval in Japan and the EU, but Spicer says those countries are likely to wait on the FDA before making their decisions.

And because Biogen fell short of having two positive late-stage studies, giving the drug an approval but mandating post-market analysis may be the direction the FDA chooses to go.

Who’s going to pay for it?

“In the old days, you just had to worry about the FDA approval,” LaMattina says. “Now you have to worry about payers putting your drug on their formularies. So, this is going to be a dicey situation for aducanumab.”

Analysts estimate that aducanumab could cost as much as $50,000 a year, raising the critical question of patient affordability. Can America’s health care economy withstand the weight of aducanumab, given the millions of Americans who might be eligible to receive the drug?

It’s a piece of the puzzle that would need to be solved quickly, Fillit says, given the overwhelming patient demand that could follow an approval.

“If it’s approved I think there’s going to be a lot of patient demand for it,” Fillit says. Even with the various concerns surrounding aducanumab — such as efficacy and price — Fillit, who has been treating Alzheimer’s patients since 1980, says that doctors are still likely to get on board with a new drug that’s been approved.

“There may be doubters, but for most of us, there’ll be good reason to at least try the drug for our patients and get some clinical experience with it,” Fillit says.

Life without a cure

“This is far from a perfect drug,” Atri says. “It has modest efficacy. But this is going to be the tip of the iceberg for a new generation of Alzheimer’s drugs.”

Despite its flaws, many argue that approving aducanumab is critical to building what caregivers are going to need for Alzheimer’s in the long-run: an arsenal of multiple treatments.

“If we look at other diseases of aging like cancer or hypertension — none of these are treated by just one drug,” Fillit says. “There are so many pathways with cancer and the same is probably true for Alzheimer’s.”

In the meantime, prevention remains the best medicine for Alzheimer’s. Get good sleep, eat healthy and stay fit — mentally and physically.

“A recent report in Lancet estimated that 40 percent of Alzheimer’s cases could be prevented by lifestyle and co-morbidity management,” Fillit says, explaining how, if people used prevention methods to delay the onset of Alzheimer’s by five years, it could potentially reduce the number of patients by 50 percent — an achievable goal that could lower the globe’s Alzheimer’s burden.

Prevention will also remain important because when it comes to unlocking the secrets of Alzheimer’s, drugmakers still have a long way to go.

“We’re still in the early days of understanding this disease,” LaMattina says.