Without the coronavirus pandemic, it’s possible that the impact of Rosemary Gibson’s work would have mostly been felt inside the policy and industry circles of pharma. But in the topsy-turvy world of COVID-19, experts have suddenly been propelled to a new kind of notoriety as they’ve been called upon regularly to explain the various issues in our health care system — Gibson among them.

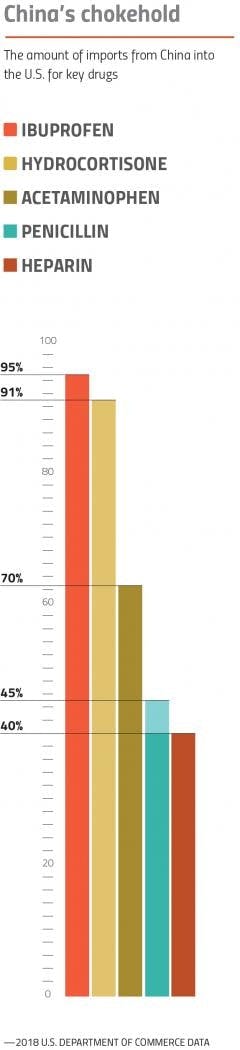

Since publishing her book, “China RX: Exposing the Risks of America’s Dependence on China for Medicine,” in 2018, Gibson has been kicking up a storm about our over-reliance on drug imports — particularly active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for generic drugs. And evidence of our vulnerability to China’s control of the drug supply was on display even before the coronavirus.

In 2018, a massive recall of blood pressure medications swept through the industry, triggered by tainted APIs from China. By the end of 2019, the push to improve the quality and security of America’s global supply chain was gaining bipartisan steam in Congress.

Then, the pandemic struck. As U.S. hospitals reeled, shortages of personal protective equipment and essential medicines gripped the public consciousness and revealed weaknesses in our health care supply chains. The finger pointing and calls for change were swift — and the revelations about America’s vulnerable supply chains collided with coronavirus frustrations and an anti-China drumbeat growing louder among some lawmakers.

Cue the “China virus.” Cue an increasing sense of nationalism about America’s drug supply. Cue the calls to put drug manufacturing back on home soil. Cue Rosemary Gibson.

“It’s a great day for our country,” Gibson said in mid-May on a prominent daily radio show.

Her appearance was scheduled within days of the U.S. government announcing an agreement worth up to $812 million with Phlow Corp., a startup in Virginia promising to provide end-to-end manufacturing capabilities for a host of essential generic medicines.

“Tomorrow morning, Americans will be going to work to make critical medicines that we need to help people with coronavirus recover. Those medicines will be made right here, in the United States of America,” she said.

The movement to reshore generic drug manufacturing to the U.S. was truly underway.

The case for reshoring

In the months following the Phlow announcement, the efforts to support American generic manufacturing gained momentum. In addition to quality and supply concerns, the implications for America’s national security continues to play a dominate role in calls for reshoring.

China hasn’t withheld drugs from America yet, but as trade tensions rise, turning off the drug spigot remains an option for Beijing. In late August, as if to prove the point, the South China Morning Post reported that a high-profile economist and government advisor in China suggested that Beijing should weaponize its exports of drugs if the U.S. cuts off its supply of semiconductors.

“We will not take the lead in doing this, but if the U.S. dares to play dirty, we have these countermeasures,” the Chinese advisor, Li Daokui, said.

With these threats looming, arguments for moving production away from China have found a welcome home in the White House.

In August, President Trump signed an executive order with provisions that require that certain government agencies begin buying “essential medicines” — which will be determined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration — from companies in America. The so-called “Buy American” order exempts certain drugs if they are already in abundant supply or if procuring them in the U.S. would increase the cost by more than 25 percent.

Yet, a major problem has been hanging over the White House’s approach — the pharma industry isn’t exactly enthused.

With each new executive action, blowback from trade groups has intensified. Although industry discontent started with widespread acknowledgement that the U.S. has lost too much manufacturing ground in the market for generic drugs, concerns about the deals the government has struck and the mandates being handed down are creating friction in the efforts to bring essential medicines production back home.

Rising China

Behind the scenes, Gibson is humble and thoughtful as she describes China’s “deliberate strategy to drive Western companies” out of the generic drugs business.

Despite the fact that her work plays into the suspicions and hostility towards China that has seized political discourse on the right, Gibson maintains that she isn’t aligned with any special interest — and that, in fact, being an outsider has allowed her to more openly speak the truth.

Although she has become a leading voice on the issue and has testified before Congress, Gibson was by no means the first to report on it. For over a decade, the story of penicillin has often been cited as a grim case-in-point.

After World War II, penicillin was mass manufactured in plants around the U.S. But in the 1980s, China upended the market by making major investments in penicillin fermenters, which sunk its price on a global scale. In 2009, The New York Times reported that Bristol-Myers Squibb had shuttered the last plant in the U.S. that manufactured APIs for antibiotics like penicillin, leaving the U.S. exposed to any supply chain disruption that could arise.

Within a few years of BMS’ plant closure, lawmakers began to express anxiety about America’s over-reliance on China for several essential drugs and the FDA’s lack of adequate data on exactly how much APIs the U.S. is sourcing from abroad. Over 10 years later, the story is much the same.

Although the FDA knows the number of API facilities in the U.S. and abroad, the agency still doesn’t track the exact volume of imports for APIs into the U.S. supply chain. In “China RX,” Gibson claims that China controls 80 percent of the U.S.’s supply for core generic drug components — an estimation that is now frequently cited as proverb by lawmakers and often in the press. In reality, the exact volume is anyone’s best guess.*

There is substantial evidence, however, that generic API manufacturing capacity is growing overseas. Every year in the Federal Register, the FDA releases its outline of fees being levied under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). In addition to collecting fees for new generic drug approval applications, the FDA also sets a rate for API plants based on the number of facilities calculated from generic drug submissions.

In the last few years, the number of generic API facilities identified in the U.S. has remained stagnant — 81 for fiscal year 2021, 76 in 2020, and 79 in both 2019 and 2018.

Internationally, however, the number of generic API facilities continues to climb — 583 were identified for fiscal year 2021, up from 548 in 2020, 534 in 2019 and 513 in 2018.

“With the GDUFA fees, one of the things that has come to light is the smaller number of facilities that manufacture APIs in the U.S.,” explains John DiLoreto, executive director of the Bulk Pharmaceuticals Task Force, a trade organization representing API manufacturers. “The smaller the universe of domestic API manufacturers you have, the more pressure there is to bring more manufacturing capacity back to the U.S.”

When looking further up the supply chain at key starting materials (KSMs), the needed precursors for APIs, the situation could be even worse.

“A lot of these are both basic commodity and specialty chemicals,” DiLoreto says. “There might be a few key suppliers in the U.S….but KSM manufacturers are scattered around the world and centered in China.”

Much like APIs, the economics of making KSMs are not on America’s side. Manufacturing KSMs is widely considered a dirty affair that can generate a large amount of toxic byproducts and waste, making China — where environmental regulations are generally not as strictly enforced as in the U.S. — a more desirable locale for production.

For generic APIs, the high cost of keeping up with FDA regulations also continues to play a strong role in diminishing the appeal of American manufacturing. While U.S. facilities have to prepare for FDA inspections that occur — often without warning — at least every two years, overseas companies are not investigated as often and always know when the FDA is on the way.

“API manufacturers want a level playing field,” DiLoreto says. “It takes a lot of resources to put a quality program in place.”

But despite this backdrop of challenges keeping generic drug manufacturing out of the U.S., Jonathan Kimball, the vice president of Trade and International Affairs at the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), the U.S. generics industry’s largest trade organization, argues that the supply chain issues may not be as bad as they seem.

Is reshoring even necessary?

When asked if the concerns surrounding China’s control of the generic drugs may be overblown, Kimball doesn’t hesitate.

“Definitely,” he says. “When you look at how the generics industry has performed since COVID, for the vast majority of products, the market has operated very well.”

One of the biggest concerns since the coronavirus pandemic began is that supply chain disruptions could trigger drug shortages.

For years, the FDA has leveraged a number of tools to help mitigate drug shortages and the efforts have paid off. In the last decade, the number of new shortages reported each year has fallen dramatically. (The total number of drugs on the FDA’s shortage list, however, has stubbornly hovered each year around 100.)

In late February, Stephen Hahn, the FDA’s commissioner, tweeted that no drug shortages had been reported — even for the 20 drug products sourced solely from China — because of COVID-19. Some shortages did arise in spring, especially as demand spiked suddenly for certain medicines, such as hydroxychloroquine. Yet, many of those shortages were quickly resolved.

“In the instances where there have been shortages, it’s because companies could not have predicted the necessity of the COVID-related drugs,” Kimball maintains.

Rather than reshoring production, Kimball and others argue that if America wants to bolster its generic drug supply chain, there is a better way.

Alternate supply chain fixes

“Reshoring sounds for some like a silver bullet,” says Vincent Colicchio, vice president and head, Supply Chain and External Manufacturing — North America Generics at Dr. Reddy’s. “But at Dr. Reddy’s, that is not a foregone conclusion. We will evaluate reshoring on a holistic basis and determine the benefit over the long term.”

Based in India, Dr. Reddy’s is one of the world’s largest generic drug manufacturers. Currently, Colicchio says that Dr. Reddy’s manufactures 70-75 percent of its finished dosage forms for the North American market in India and the U.S. Because India is also a purchaser of APIs sourced from China, the country has been affected by many of the same supply chain concerns as the U.S. To make sure that the company does not experience severe disruptions, Colicchio says that Dr. Reddy’s is taking several measures to “de-risk” its supply chain.

The idea, Colicchio says, is to always do a bit of doomsday prepping in order to make sure that any sudden shift in demand will not quickly deplete stocks.

“We strive to maintain sufficient finished goods inventory levels with at least two to three months on hand. That’s why it’s critical to procure sufficient levels of APIs and other raw materials.” he explains. “In pandemic conditions, it is advantageous to target having at least three to four months of API supply available to deal with potential disruptions, which will also help stabilize your cost of goods in the event that suppliers increase API costs.”

Colicchio also argues that reshoring in America could put patients at risk by potentially causing dramatic price increases.

“If the federal government mandated that companies had to produce a high percentage of pharma products in America within the next 10 years in order to minimize the dependence on India and China, that ultimately will cost them more — not 10 percent more, but potentially 30-40 percent more.”

To be further prepared for sudden API supply shortages, Colicchio says that companies should also ensure they have secondary suppliers lined up.

“Let’s say the FDA inspects one of your API suppliers and identifies there are significant compliance gaps at their production facility. They could halt API production — for weeks to months — until the compliance violations are remediated,” he says. “You need to have a secondary API supplier in place to ensure business continuity.”

DiLoreto also argues that moving production to the U.S. isn’t going to eliminate supply chain risks.

“It would be great if we could identify all of the KSMs and APIs and bring them back to the U.S., but then you don’t have redundancies,” DiLoreto says. “What if you were manufacturing in the U.S., let’s say in Florida, and there was a hurricane coming? Then what would you do?”

Kimball also points out that despite the threatening rhetoric from Beijing, there are major financial disincentives in China to cutting America off.

“China is an important part of our industry, so we hope that they will continue to play a responsible role in delivering medicines,” Kimball says. “But the real goal is ensuring that there are redundancies so that if there are disruptions, other countries are able to stand up and produce more of what’s needed.”

Yet, despite the efforts from regulators and industry to shield the generics supply chain from hiccups, and the arguments that the market is generally performing well, the push to reshore production — at least for “essential” medicines — is clearly on course. Now the question is: How can the industry get in on the action?

Engaging the industry

For proponents of reshoring, the generics manufacturing deal with Phlow was the first victory on a road being built to create jobs, provide economic stimulus, and reduce our reliance on API imports. Months later, another deal to make generic APIs was announced — this time it was a $765 million loan with long-time camera and chemicals maker, Eastman Kodak.*

But inside the generics industry, many were scratching their heads. Why did the first major contracts created to reshore essential medicines production go to companies without a proven track record in generic drug manufacturing?

“Almost every one [of the manufacturing companies] said, ‘How do we get considered for a deal like that?’” explains DiLoreto. “As existing API manufacturers, they were dismayed by not having an opportunity to be a part of any government effort to increase API manufacturing.”

This lack of engagement from the White House didn’t set a cooperative tone. As far as DiLoreto knows, the generics industry was not approached before the Phlow or Kodak deals were finalized and there was no apparent bidding on the contract.

“I think there was a lot of concern that these contracts were given to any existing manufacturer…without looking at how [the government] could get a good deal by inviting competition,” DiLoreto says. “It was a fire, shoot, aim approach. They are jumping into the river but don’t have a boat yet.”

Kimball would not comment on whether or not AAM was contacted by the White House ahead of the Phlow announcement. But, he said that AAM is in talks with a number of people in the Trump administration about what can be done to attract additional investment for its member companies.

“Our policies have received strong support from the Trump administration,” Kimball says. “We’ve had a number of good discussions and we hope that as policies develop further we will continue to engage in those conversations and they will be supportive of broad-based generics manufacturing.”

The policies Kimball is referring to were included in AAM’s “Blueprint for Enhancing the Security of the U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain,” which was created by the organization to demonstrate how the White House should use more carrots than sticks to make reshoring attractive.

Show me the money

Since the “Buy American” policy was first floated by the White House this spring, the issue has riled the entire pharma industry — from branded to generics. Although there is support for some of the measures in what became Trump’s executive order in August — such as identifying vulnerabilities in the supply chain — many contend that mandating government purchases from U.S. suppliers could do more harm than good.

In June, Stephen Ezell, vice president of Global Innovation Policy at Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington think tank, published an in-depth smackdown of the order, concluding that “Buy American policies…could unwittingly reduce supply chain resiliency, while doing little to boost U.S. innovation competitiveness.”

“A better solution would be to use financial incentives,” Ezell says.

Among the policy initiatives that Ezell recommends are more investment in R&D for advanced manufacturing processes and leveraging the tax code to encourage greater levels of drug manufacturing.

“America needs policies that encourage but don’t compel the reshoring of production,” Ezell wrote in his analysis.

AAM’s “Blueprint” involves similar policy recommendations, including a 50 percent tax credit to “offset the costs of manufacturing medications on the priority medicines list.”

“Our proposal involves everything from tax incentives to grants to an international trade agreement that recognizes the value of the global supply chain,” Kimball explains.

Overall, Kimball says that the U.S. should focus on ways to make reshoring a safe bet for manufacturers.

“How do you create a system in the U.S. that encourages generic production that is competitive and doesn’t lead to higher prices? That is the equation that we think is going to be very difficult to answer,” he says.

Yet, as the deal with the U.S. government shows, Phlow Corp. thinks they have an answer.

Intensifying the process

Despite the eyebrows that were raised after the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) announced that it had tapped a newcomer on the generics scene to receive the massive manufacturing contract, Dr. Frank Gupton, one of Phlow’s co-founders, says that having a bit of outsider perspective has given the company an edge.

Launched with CEO Eric Edwards — who previously co-founded a pharma firm called Kaleo —Phlow has been willing to approach generics manufacturing with fresh eyes to see how the system can be improved, says Gupton, a longtime pharma and chemical engineer.

The impact of the CARES Act

In March, Congress passed sweeping legislation aimed at providing economic relief during the pandemic. The CARES Act also included key provisions for drugmakers designed to mitigate coronavirus-related shortages that could also reveal more about America’s supply chain for generic drugs including:

- Expanded reporting requirements for potential shortages, including projected API shortages and reasons for the shortage

- New volume data on the “amount of each drug … that was manufactured, prepared, propagated, compounded, or processed … for commercial distribution” in the U.S.

- The new reporting requirements were supposed to take effect on Sept. 23, but the FDA recently stated that the electronic portal it is creating for data submissions isn’t up and running yet.

Originally, Edwards and Gupton had set their sights on manufacturing hospital treatments for pediatric patients struggling with rare, genetic diseases. But Edwards was also struck by another problem: hospital patient deaths due to drug shortages. With Gupton at his side and the coronavirus spreading, the pair eventually sharpened their focus on manufacturing essential medicines. Recognizing that they could help provide a solution to shortages, Edwards contacted the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and pitched an idea for end-to-end manufacturing. Through this relationship, the BARDA deal with Phlow was born.

Now, the name of the game at Phlow is process intensification. In addition to using automated continuous manufacturing methods to produce APIs, Gupton says the company has been tweaking the process to make it more efficient and environmentally friendly.

“One of the areas I was always concerned with is catalysts,” Gupton explains. “There is one that is used a lot in API manufacturing that is made from heavy metals that are highly toxic. You have to do multiple operations to purify the drug.”

Using a new technology, Gupton says that Phlow is able to “immobilize the catalysts on a solid support to separate them,” which he says improves the process, reduces waste and “has a much smaller footprint than in the past.”

“No one has committed to this kind of low-cost, automated manufacturing,” Gupton says.

As part of the four-year $354 million contract BARDA (which includes a potential $458 million option after the base period to maintain long-term sustainability), Phlow will set up end-to-end capabilities to manufacture essential generic drugs for the strategic national stockpile using KSMs sourced from AMPAC Fine Chemicals, APIs made by Phlow, and finished dosages produced by Civica RX, a nonprofit created in 2018 to manufacture generics for a consortium of health systems and hospitals. Gupton says that if a particular KSM is not available in the U.S., AMPAC will find a workaround by using a different chemical or engineering process.

Under another deal with HHS, Phlow has already delivered more than a million doses of five different drugs for the national stockpile. Gupton says that Phlow, which is registered as a public-benefit corporation, doesn’t know exactly when it will start cranking out essential drugs for the BARDA agreement, but that it could be a few years.

“We’ve got our heads down,” he says. “We’re working hard every day.”

Gupton says that Phlow plans to price its drugs lower than other generics on the market, but doesn’t know how much lower that price will be yet.

“Our goal is to be competitive,” Gupton explains. “We will look at every aspect to make sure that we’ve identified every opportunity [to keep prices low].”

One thing that is for certain: Even without the U.S. government investing in reshoring, the tide could be turning against Chinese drug manufacturing.

America or bust

The way Harry Moser tells it, American industries have been “spoiled” by China for far too long.

“China is now looking to clean up its environment, so over time, they will not be as enabled for low-cost manufacturing,” Moser, president at Reshoring Initiative, a think tank/trade association aimed at bringing manufacturing back to the U.S., says. “If [the generics industry] thinks they’ll be saving money by having the Chinese dump their chemicals into a river, that won’t happen forever. That advantage is going to be taken away.”

Gupton also sees the market shifting away from favoring China in the long-run.

“The current issues associated with sourcing health care out of China are quite obvious,” Gupton says. “However, over the long-term, the federal government is in the process of creating a more level playing field for U.S. manufacturers to effectively compete with Chinese health care providers for formulated products and active ingredients, as well as key building blocks to produce these materials.”

The current landscape may still be tilted in China’s favor, but Moser is unmoved by arguments that America can’t rebuild its generic manufacturing infrastructure.

“Can it come back in five years if companies get started now? Or would you rather still be dependent on China?” Moser posits. “Or are you willing to put in the effort, money and work to be self-sufficient again?”

Although Republicans have wholeheartedly embraced the issue of wrestling manufacturing out of China’s hands, bipartisan support for producing essential medicines in the U.S. remains strong. None of the experts interviewed for this article think that the results of the 2020 presidential election will hinder the momentum towards reshoring.

“We wouldn’t lose steam under [Joe] Biden,” Moser says.

Yet, there is hope in the industry that instead of one-off measures, the government will come forward with a comprehensive, long-term plan to make reshoring more beneficial for companies here.

“The government hasn’t yet engaged the generics industry the way they have with [coronavirus] vaccine manufacturers like Moderna, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, GSK, etc., and also with new alliance corporations to provide COVID-19 pandemic medicines,” Colicchio says. “Engaging generics companies now to open a dialogue to provide affordable medicines is an important step that will help.” DiLoreto agrees.

“If the whole point of reshoring is to ensure that we have essential medicines in the U.S., then we should know what those drugs are, how we get them here and start laying the groundwork for how we can manufacture them in the U.S.,” DiLoreto says.

Going forward, Kimball says that the industry will need the government to be a financial partner in the efforts to bring generic manufacturing back.

“What the Phlow contracted demonstrated is that you need government investment,” he says.

As for Gibson, she’ll still hold a front row seat in the efforts to reshore for the foreseeable future. Now a member of Phlow’s board of directors, Gibson says she’ll use her role to help ensure that the company continues working “in the public interest.” She also points out that it will be up to other companies in the generics industry to demonstrate that they’re willing to do their part to secure America’s supply of generic drugs.

“We have had drug shortages in this country for 20 years and nobody stepped up to the plate to offer to help fix them. Nobody,” she says. “You have to show that you’re willing to help — not just to take, but to give.”

Footnotes:

*Some have publicly questioned the validity of Gibson’s 80 percent estimate, which includes KSMs and APIs, that she says was based off a comparison between the U.S. market and an estimate made by the Indian government, who stated that they receive about 70 percent of their KSMs from China. “If India is in that situation then the U.S. must be in at least the same situation,” she says. “Add on top of that the substantial percentage of APIs we get from China, and that’s how I came up with 80 percent.” That figure is also in line with estimates from other major countries — such as Russia — about the volume of generic API imports they receive from China.

*Within days of the Kodak announcement, the loan was put on hold after the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched an investigation into potential wrongdoing associated with trade and executive stock purchases made around the time the deal went public. The loan will remain on hold until the SEC completes its probe, which could take months.