Still got it: Tips and tricks to keep your older pharma plants riding high

Everything you do in life catches up to you eventually. And just like the state of your complexion, pharmaceutical equipment loses its pep over time and cracks around the edges. Of course, these breakdowns are not only cosmetic. Without proper maintenance and occasional upgrades, old and faulty pharma equipment can increase the risk of contamination, which can trigger recalls and quality-related disruptions in production that don’t just slow down work at one plant — they can also be a major contributor to U.S. drug shortages.

In pharma plants, age definitely matters.

Ironically, there’s no shortage of new equipment that manufacturers can buy to replace their older machines. Walk the floor of any industry trade show and you can easily get lost in the sea of snazzy new isolators, tablet presses, packaging robots, fill and finish machines — the list goes on. But in a pharma plant, pulling off this “swaperoo” is much more complicated than chucking out an old machine and then plugging in a new one to replace it. In fact, the process can be a regulatory quagmire that companies aren’t likely to emerge from for at least a few years.

Manufacturing equipment is also a major investment and it’s no wonder companies want to put off replacing them to get as much mileage out of their equipment as they can. On top of that, there can be uncertainty involved in trying a new kind of equipment and a learning curve that could lead to production disruptions. Overall, this slow timeline for regulatory approvals and a fear of the unknown creates an environment that makes pharma companies wary of change.

“When it comes to new tech, no one wants to be the first to implement it — but everybody wants to be the fastest second,” says Maik Jornitz, president and CEO of G-Con Manufacturing, and co-chair of the Parenteral Drug Association’s (PDA) former Aging Facilities Task Force.

Yet, there are plenty of compelling reasons to give your aging facilities a needed facelift. Although the regulatory challenges are real, they’re not insurmountable and can often be conquered in a way that’s easier than companies realize. Also, putting off the process only delays the inevitable breakdown or a regulatory citation that’s likely to be more costly in the long run than an upgrade would have been.

Here, we’ll explore the critical link between these manufacturing issues and widespread drug shortages, provide real-world tips on how companies can improve quality control in aging plants, and explain why it pays to update older facilities.

The drug shortage link

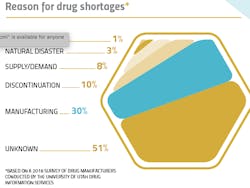

Throughout 2018, the number of drugs and medical supplies in short supply in the U.S. hovered around 200. It’s certainly not a new issue — back in 1999, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration launched a Drug Shortage Program to help conjure up solutions for keeping a healthy supply of the country’s high-demand medicines. Yet, the problem continues to vex regulators and the industry.

Since Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, creating production delays from one of the country’s hot beds of pharma manufacturing, this natural disaster has often taken the blame for ongoing shortages. But manufacturing hiccups that hamper product quality have been shown to be a much bigger culprit of supply problems. The issue is particularly acute in aging facilities where the use of older equipment can lead to higher rates of contamination.

A 2018 survey conducted by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) asked pharma manufacturers to identify the cause of shortages, the most-cited known reason was “manufacturing” issues (30 percent). The FDA has also estimated that over half of injectable drug shortages are due to quality problems such as particulate contamination. According to ASHP, the rate of shortages is increasing and “severely impacting patient care and pharmacy operations.”

Of course, no manufacturer wants to produce contaminated products, especially for critical medicines. But unfortunately, the economics of producing some types of drugs doesn’t provide incentives for making the needed investments that could help avoid problems with impurities.

Although the drugs on the FDA’s shortage list include a wide range of treatments, the majority are the most basic products for everyday patient care in hospitals, such as sterile water, lidocaine, saline, bupivacaine, and several kinds of opioids. These high-demand, older products also have low profit margins — making investments into production lines for the drugs less attractive.

Last November, the FDA held a conference on the issue of drug shortages and one panelist summarized the situation by saying that in short, the market doesn’t put a premium on creating a high-quality, reliable supply for these drugs.

How old is too old?

There’s no easy way to define what makes a pharma plant officially over the hill. Some experts have estimated that most pharma facilities are designed to run well for about 20 to 25 years. And because all plants are in various states of aging — in regards to both equipment and the facility — it’s difficult to get a handle on how many plants in the U.S. have passed the 20-year mark. But Sue Schniepp, a distinguished fellow with Regulatory Compliance Associates, has seen plenty of first-hand evidence that operations in some plants look like they’re from a bygone era.

“The oldest line I’ve seen was about 50 years old,” she explains. “The company had a completely open line, and the only protection was a shower curtain.”

According to Jornitz, lines that are operating with frequent interventions, such as those susceptible to glass breakage, are at the highest risk of contamination.

“It’s important to take the human factor out of the equation,” he says.

Jornitz says that the fill lines are often the most vulnerable to contamination issues, but that older utilities, such as outdated water systems, can also put products at risk. Schniepp agrees that contamination risks go beyond equipment.

“It’s also in the floors if they’re not state-of-the-art,” she says. “You have to also look at the ceilings — anywhere you’re bringing the walls and ceiling together there’s a gap that could harbor microbes. It’s one thing to put in a restricted access barrier system (RABS). But if there is microbial growth in some of the plant’s older joints, what good have you really done?”

Anti-aging for pharma plants

Naturally, regular maintenance and upgrades can go a long way in preventing some of these problems.

“All facilities are aging,” Jornitz says. “However, when the company is reinvesting funds into the facility and have rigid maintenance or technology improvement cycles, the facility can age much slower.”

One of the challenges, however, is that companies are often reluctant or unable to shut down their line to perform maintenance updates.

“When you’re a contract manufacturer especially, sometimes you’re running around the clock,” Schniepp says. “But you have to shut it down to see what’s wearing, what’s tearing — and jump on it before it becomes a problem.”

Despite the one-week shutdown that’s typically required for a maintenance check on a company’s line, Schniepp points out that it’s better to spot cracks in the system when it’s down because when it’s running, operations can start to “go awry.”

“Look at the line holistically and make sure the equipment is working together,” she says.

Jornitz also recommends that companies use predictive maintenance to proactively improve the most important parts of the process steps. Additionally, he says that companies often neglect the importance of their equipment supplier relationships and don’t keep track of the availability of spare parts for their machines.

“It’s very important to get early warnings from the supplier that one of their equipment pieces is turning obsolete, so the end-user can act accordingly,” he explains.

And putting off these kinds of assessments is likely to haunt companies in the end. Ronald Berk, chief technology officer and principal consultant at Hyde Engineering + Consulting, says that about half of the companies he’s worked with on updating aging facilities are in some kind of regulatory trouble.

“We worked for a company that constructed their manufacturing facility in the late 90s, and the drug they produced was in such high demand that there was a capacity shortage, and they never upgraded the facility,” he recalls. According to Berk, the company didn’t want to slow down production of the drug, so it “hit the snooze button for 20 years,” and never stopped to maintain and improve quality at the facility. Then, after the FDA inspected the facility, the company ended up in a consent decree situation (where the company enters an agreement with the FDA to improve parts of their line that are in violation of regulations).

It’s exactly this kind of regulatory scrutiny that should motivate companies to upgrade.

A tale of upgrading success

One of the major challenges companies face when dealing with aging facilities is navigating the landscape of regulatory requirements. In particular, companies are reluctant to install new equipment that the FDA could consider a major process modification under its Post Approval Change (PAC) rules. When this occurs, companies often have to revalidate their line, or go through all the tests needed for completing a prior-approval supplement (PAS), which can take as long as four years.

In 2014, the FDA set out to address this major regulatory hurdle by offering alternative avenues to updating technology. Now, the agency will allow companies to make updates to their operations without a PAS if the new technology is considered a “like for like” change with the older equipment. It’s this route that Schniepp used to completely overhaul the line of one CMO where she worked — a major process she was able to get to the finish line in about two years.

“By doing ‘like for like’ you still have to do media fills and qualifications of the line, but you can do it without going through the PAS — as long as you don’t change the footprint of the line,” she explains. “It would be like upgrading the vanity in your bathroom.”

Here are the major challenges Schniepp faced and how she worked with the company to overcome them:

Culture and communication: While working as the vice president of Quality for the CMO, Schniepp was tasked with updating a line that was the workhorse of the company, about 30 years old and produced 75 percent of its products. But in the depyrogenation tunnel, the cooling piping was above the products, which was causing fluid to sometimes drip into the vials. The contamination had cost the company approximately $28 million in lost products and triggered an FDA inspection. Yet, Schniepp still faced resistance to change.

“When you’re a CMO, your culture is to please the client,” Schniepp says. “When we wanted to upgrade the line, we had to coordinate between about 15 clients that had products on the line and get them all to agree on one approach.”

According to Schniepp, not all of the clients thought the “like for like” approach would work. While some were worried about the downtime involved in undergoing a potential PAS, others believed the changes could possibly be communicated to the FDA on an annual reportable. To get everyone on the same page, Schniepp made sure that she wasn’t just talking to the quality department of every client, but also bringing each company’s regulatory head into the discussions to get their input and help company leaders feel more confident in her plan.

Schniepp also ran her plan past the FDA to make sure the agency didn’t have any major concerns with the approach

“What regulators really want to see is: Have you thought this out? Can you defend your case? And is your product going to be as safe and effective as it was before? That’s how you win this game,” she says.

Working in stages: Once it was time to implement the upgrades, Schniepp says it was all about planning ahead to make sure the company had adequate supplies of its products to offset downtime in operations. The company worked to replace the entire line during a four month period using the comparability protocol specifying before-and-after results for the product requirements for the manufacturing line being replaced.

All told, Schniepp says it took a total of two years to update the aging line. Although the company had to deal with about four months of downtime during the process, it was much less of a burden to operations than it would have been to change the entire line under the PAS paradigm.

Training: Importantly, Schniepp says the company made sure to adequately train employees with the new equipment so that they could hit the ground running.

“We set up the line in a warehouse so the operators could work with it without making any products, because it was so different,” she explains. “They had to learn how to clean the RABS and change out the parts. All of that was going on while we were developing the comparability protocol for shutting down and restarting the line.”

Pain points

Just like when you’re making updates in your home, Berk says that pharma companies often fail to plan for unexpected bumps in the road when revamping their operations.

“One thing that gets underestimated is that if you have an old facility and you start trying to fix things, you might discover other things that need to be fixed or some equipment might break,” he says. “So some kind contingency plan for that is good.”

According to Berk, companies also often overlook the life expectancy of their automation and control systems, which can be much shorter than mechanical systems. Changeover to a new control system can also be more challenging than companies realize.

“The reality is that you need to spend quite some time testing and qualifying your control system, which can be very time consuming, and inevitably leads to a long downtime,” he explains. “I’ve been at sites where clients wanted to switch overnight. But the process can take up to a month — or half a year if it’s a large facility.”

The road ahead

There is hope on the horizon in the form of the industry’s newest technologies, if pharma companies are willing to adopt them. The rise of single-use equipment, for example, could help lower contamination rates, especially because they allow companies to forgo much of the water utility systems needed to clean stainless steel parts.

There could also be changes on the regulatory front and the FDA has demonstrated a commitment to helping companies make needed upgrades.

PDA disbanded its Aging Facilities Task Force in 2017, but the organization has since launched a new task force aimed at addressing the challenges of Post-Approval Changes. One of the group’s main efforts is to encourage the harmonization of the global regulatory approach to PACs so that companies don’t have to undergo separate approval processes for upgrades in different countries. If other countries accepted an FDA approval, for example, it could shave years off of the process.

“The No. 1 question is: How can new, robust technology be implemented faster?” Jornitz explains. “But also, how can we help harmonize global regulations?”

But for too long, Jornitz says that the industry has used this regulatory hurdle as an excuse for not updating their facilities.

“Ultimately, running assets until they break down will cost much more than continuous improvements,” Jornitz argues. And when it comes to dealing with the red tape, Jornitz says that companies that are updating aging tech have a strong case to make with regulators.

“If they can show that new technology improves patient safety and avoids drug shortages, I think regulators will listen,” he says.