"I became aware of a growing myth on Capitol Hill about the Housewife from Connecticut. They told each other, ‘She’s no housewife’ but I knew I really was. I simply honed skills attained in the PTA and Scouts to fight City Hall on a larger scale, all the while hoping I would get home in time to do laundry or cook.”

These are the words of Abbey Meyers, a self-described 1970s housewife who not only went on to found the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) but who is also considered the primary consumer advocate responsible for the passage of the Orphan Drug Act of 1983. Meyers’ mission went into high gear when the medication her son was taking to treat his Tourette’s syndrome became unavailable after the sponsor, a division of a major drug company, cancelled the trial.

While Meyers is nothing short of a legend in the rare disease world, you don’t have to look far within the space to find an inspiring story about a determined parent who fiercely advocated for their child’s diagnosis and treatment.

“The industry is full of these stories. While each is special, unfortunately they are not unique. There are lots of parents who have kids diagnosed with a rare disease and despite having no medical backgrounds, they’re just not willing to watch their kids die,” says Tim Coté, former director of the Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD) at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Thus, the rare disease space became quite literally a mom-and-pop industry — where everyday people become advocates, fundraisers, lobbyists and researchers. The niche space has been painstakingly built on the backs of patients and caregivers, with many treatments either compounded for individual patients in labs run by academic institutions or manufactured by small, newly formed biotechs.

Notably absent in the scrappy history of orphan drugs are multinational pharma giants. The very term “orphan drug” has its roots in the pharma industry’s lack of interest in the rare disease space. The term was first coined by a pediatrician in 1968, who lamented the “orphaning” of the pediatric population given few drug developers found it worth the cost of studying drugs in children. But it was not until 1982 that Dr. Marion Finkel, the first director for the FDA’s OOPD, championed the use of the term exclusively for rare disease therapies in place of the less palatable “significant drugs of limited commercial value.”

Now, 35+ years after the passage of the pivotal Orphan Drug Act, the pharma industry has seen incredible scientific advancements and an evolution in regulatory guidance. Personalized treatments tailored to specific genetic profiles as well as cell and gene therapies with the ability to cure disease are in the pipelines and on the market. And increasingly, as the industry becomes more adept at developing drugs for small patient populations, multinational pharma companies are becoming more visible in what is now a swelling rare disease space.

A deeper dive into the factors motivating this shift reveals a pharma industry that, if willing to stay true to the core values of the once niche space, can realize countless benefits — for both their bottom lines and the 300 million patients worldwide suffering from rare diseases.

Then and now

While the study of rare diseases dates back hundreds of years, the story of orphan drug approvals largely began with a pivotal piece of bipartisan legislation passed into law in 1983.

The Orphan Drug Act (ODA) provided financial incentives to attract the pharma industry’s interest through a seven-year period of market exclusivity for approved orphan drugs and tax credits of up to 50% for R&D expenses (this was reduced to 25% in 2017). It also authorized the FDA to designate drugs for orphan status, provided grants for clinical testing of orphan products, and offered up the agency’s assistance in framing investigational protocols.

“Essentially they recognized that nobody was going to make orphan drugs unless there was some sort of incentive for it,” sums up Coté. “The bill was heralded as one of the most effective pieces of legislation ever passed by Congress. And the numbers actually do bear that out.”

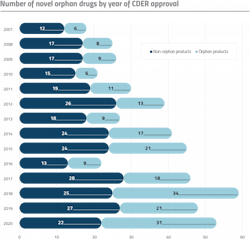

Those often-cited numbers are difficult to deny: Prior to the ODA, less than 10 orphan drug products were brought to market from 1973 to 1983. Since the inception of the Act, more than 4,500 orphan designation requests have been granted, and over 730 products have been developed and approved for more than 250 rare diseases.1

And yet, despite the incentives offered by the ODA, passing the law was not an instant floodgate for orphan drug development.

“The big companies really ignored the orphan drug opportunity for the first number of years after the Act, so a whole new segment of the industry grew up around orphan drugs, consisting of little companies, many of them biotech. They were the first to recognize the importance of the law and its incentives,” said Meyers, in a 2016 interview.

Coté had a similar experience while at the FDA. “So when I started at the OOPD [in 2007] people weren’t very interested in orphan drugs. I once went to visit a well-known large pharma company and I tried to talk them into making more orphans. At the time I was served some very, very nice coffee as I was sitting there in my uniform from the FDA. They all smiled a great deal, nodded their heads, and not much was done,” recalls Coté.

But today, it is unlikely that any pharma company would shrug off a discussion about a market that’s predicted to surge to $217 billion by 2024. According to Evaluate Pharma, after nearly four decades of relatively consistent growth, orphan drugs now comprise a cornerstone of the pharma market. It is so robust that rare diseases now take home the majority of drug approvals in the U.S. — in 2020, more than half of FDA’s novel drugs were approved to treat orphan diseases.

Recent acquisitions back pharma’s faith in the potential of the rare disease market. In 2019, Bristol Myers Squibb spent a monstrous $74 billion to acquire Celgene, a leader in the orphan drug space. The same year, Roche picked up Spark Therapeutics, a biotech with a focus on gene therapies for rare and genetic disease, for $4.8 billion.

Most recently, AstraZeneca unveiled the largest biopharma deal of 2020 when it announced a proposed takeover of rare disease specialist Alexion Pharma in mid-December during the COVID-19 lockdown.

“It’s probably the first time a deal of that magnitude was done without constant real-life interactions,” says Marc Dunoyer, AstraZeneca’s chief financial officer.

According to the British drugmaker, the deal, which will enable the company to establish a rare disease business unit, will also unlock a new chapter of growth.

“We know that the field of rare disease is still completely untapped. There are about 5% of diseases that are being treated with drugs that are approved by regulators. So it’s an enormous field of discovery for years to come. The global rare disease market is forecasted to grow by a low double digit percentage in the future,” says Dunoyer.

A wider net

When it comes to the public discourse about orphan drugs, the therapies with shocking price tags tend to steal the headlines. Under the Orphan Drug Act, treatments are given seven years of exclusive rights to the market — meaning the FDA won’t approve another drug to treat that rare disease until that period expires. And this, according to critics, enables monopolies and drives up drug prices.

“What happens when you make something like exclusivity the financial incentive is you get some eye-popping numbers where the average orphan drug is like 200-grand a year per patient, which is like buying a new house in a lot of parts of the country,” says Coté, explaining the public outrage.

It’s true that the 10 most expensive drugs on the market — led by Novartis’ Zolgensma, a one-time gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy with a list price of $2.125 million — are all treatments with orphan drug designations. This type of highly noticeable pricing has caused policymakers to assail orphan drugs, and the companies that make them, for contributing to skyrocketing health care costs.

But according to NORD, the leading rare disease patient advocacy organization, this is simply not true — they even commissioned a study to prove it. Ultimately, the study found that orphan drugs only account for a fraction — less than 7.9% — of total drug spending in the U.S.4 The topic continues to be the center of decades-long debate, with payers, advocacy groups and pharma companies often producing studies with conflicting numbers and lawmakers frequently proposing new legislation to refine the ODA.

But many are not convinced that it’s simply the temptation of one-off orphan drug superstars that’s driving pharma further into the rare disease space.

Take, for example, a big perk of AstraZeneca’s Alexion buy — the blockbuster Soliris. The treatment was approved in 2007 to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, a rare blood disease, and later gained additional approvals for other rare indications, increasing annual sales to $3.5 billion and making it one of the most expensive drugs in the world.

But according to AstraZeneca, there’s a bigger picture to be seen particularly in terms of Alexion’s complement biology platform.

Alexion’s legacy in rare disease is rooted in being the first to translate the complex biology of the complement system — part of the immune system that is essential to the body’s defense against infection — into transformative medicines. Alexion has applied this technology to a broad spectrum of immune-mediated rare diseases caused by uncontrolled activation of the complement system.

Increasingly, modern pharma companies are looking to these types of platform technologies in order to standardize and become more efficient; essentially applying a consistent set of well established technologies or methods to the research, development or manufacture of different products.

“AstraZeneca, with its large oncology pipeline, has experience in disease state areas that have had to be innovative and very fast paced. And so it’ll be interesting to see how they apply or don’t apply the learnings from those experiences into the rare space as they are acquiring these smaller biotech companies,” says Pam Rattananont, vice president of Development & Marketing Communications at Global Genes, reflecting on the 20 years she has spent observing the business side of the oncology space.

According to Dunoyer, AstraZeneca has big plans for Alexion’s platform.

Dunoyer highlights the opportunity for “sharing Alexion’s expertise in complement biology across the group to explore its further application in immunology and other fields of medicine.”

This type of springboard approach aligns with the history of rare disease study, which has often led to advances in broader areas of medicine.

“Studying rare diseases has informed our understanding of normal biochemistry, normal human physiology, normal functioning,” says Coté. “Take, for example, the urea cycle disorders. This is a collection of wicked rare little enzyme defects that only affect a few thousand people in the U.S., mostly children. By learning all the different ways that all these enzymes screw up and what happens as a consequence, that’s how we figured out what the urea cycle is — by seeing what was broken, we were able to determine what normal was.”

What pharma brings to the table

For many, the first thing that comes to mind when multinational pharma companies are mentioned is money — and in the case of the rare disease space, this is a big benefit.

It is estimated that close to 95% of the identified 7,000+ rare diseases have no FDA-approved treatments. This equates to a huge unmet need in the market for orphan drugs.

“When you look at it, there are a lot of small disease states that don’t have a lot of hope because there’s no therapy available. What I see as the big positive here is the pharma companies have the money to invest and to bring products to market, whereas some of these smaller companies really have a shoe string budget,” says Donovan Quill, president, CEO and founder of Optime Care, a pharmacy, distribution and patient management organization focused on patients with rare disorders.

Despite this, Coté feels it’s important to point out to pharma companies that in the orphan drug space, the spending doesn’t have to be exorbitant. A pathologist by training, Coté is busy writing a book to demystify the process of bringing an orphan drug to market, while developing his own drug to treat Behçet’s Disease, which he says can go all the way to market for a total investment of somewhere around $7 million.

“The FDA doesn’t have any rule that says you have to spend a certain amount of money on bringing drugs to market. There are a lot of rare diseases that could be approached with drugs that could be very inexpensive, so that’s the beautiful message that doesn’t always resonate in the halls of large pharmaceutical companies,” says Coté.

But before you can push potential treatments through the approval process, you need funds to begin the research — and often that’s the hiccup.

“There are a lot of rare disease states out there that just quite frankly, don’t have the funding to even get research started in some cases. With the larger pharma companies having the funding to actually look at it and to fund even just early clinical research, that’s a big positive,” says Quill.

Here, patient advocacy organizations are playing a growing role in attracting the attention of pharma companies. Global Genes, which is a global rare disease non-profit with a foundation alliance of more than 750 rare disease patient advocacy organizations, says advocacy groups are “on a mission to get industry invested in them.”

“What has changed in the landscape is that patient advocacy organizations have realized their role is not just patient and family support. They have to be drivers of research in order to gain traction with industry,” says Christian Rubio, vice president, Strategic Advancement at Global Genes.

Advocacy groups are accomplishing this by mobilizing and building umbrella organizations focused on building data platforms that span potentially related diseases, rather than phenotypic and singular gene-based diseases.

“More patient advocacy organizations are looking outside of just their own specific genetic diagnosis and defining umbrella organizations of their own. They’re building their own data sharing networks that build linkages of understanding across different molecular issues so that they can create more meaningful, insightful platforms to work with pharma,” says Rubio. “They are building the data sets of disease burden and doing enormous amounts of heavy lifting to help identify shared etiologies that will support the scaling of the development of and access to life-changing therapies.”

Don’t rock the boat, pharma

Pharma’s success in the orphan drug space will rely heavily on the industry’s ability to focus on the patient.

Rare diseases tend to have a debilitating impact on the lives of patients, many of which are children, so sensitivity to this impact is vital to the development process for orphan drugs. Every part of the process from initial research to trial designs to drug manufacturing needs to revolve around individual patient needs. Additionally, because natural history studies — epidemiological research that focuses on describing the frequency, features and evolution of a disease by collecting real-world data from patients — are often incomplete or not available for most rare diseases, every detail learned from patients is vital data.

And while the concept of patient-centricity is not new and is becoming increasingly relevant as more pharma companies move into areas like personalized medicines and gene therapies, most agree that historically, this is not a strong point for large pharma organizations.

But the pharma companies pursuing the rare disease space know they need to step up their game and fortunately, they don’t have to go it alone.

Many patient-focused organizations are more than willing to collaborate. The Global Genes RARE Corporate Alliance, for example, is a coalition of more than 100 rare disease industry stakeholders, many of which are pharma companies, who have come together to improve and expedite access to effective therapies for all rare patients.

“They’re [pharma and biopharma companies] looking for ways to better partner with the patients,” says Rattananont. “And to get that patient voice and be very patient-centric we have to work closely together to make progress.”

Quill’s company, Optime Care, is predicated on a patient-first care model. Drawing from his own family’s experience with rare disease, Quill wanted to create a company that offered specialized expertise, transcending the limitations of traditional, legacy care organizations that often fail to fully address the needs of these patients. The company has now partnered in the launch of more than 25 orphan products — and according to Quill, this can involve helping larger pharma companies adjust to cultural changes.

“Our job as professionals in the industry with the experience is to try to either change that mindset or prevent the larger pharma companies from trying to do what they would do for their massive patient populations. We want them to think differently,” says Quill.

“Sometimes it’s like moving the Titanic, but I think it’s an opportunity for large pharma companies to really start taking a patient-first approach to what they do.”

For pharma companies making acquisitions in the rare disease space, there’s also a great opportunity, if they are willing, to learn from the specialized experience of companies they are buying.

To this end, AstraZeneca has chosen to keep the Alexion business as a separate business unit, maintaining its Boston headquarters.

“The sort of philosophy we’re going to utilize is going to be ‘autonomy with bridges.’ So, what does this mean? It’s not autonomy with walls. You’re not living in a sort of a fortified city where you are autonomous but have walls around your city. You have your own city, you have your own decision-making, but you can, and you should, leverage every capability that you can from AstraZeneca,” says Dunoyer.

Sharing the seas

During our interview, Rubio referenced a startling piece of insight that had been shared at a recent Global Genes symposium: Considering it has taken over 35 years to find treatment for roughly 250 rare diseases, if we continue at this rate, it will take approximately 2000 years to find cures for all the known rare diseases.

“Just like the internet facilitated the explosion of crowdsourced content and democratized media, and elastic computing lowered barriers for new tech ventures, the federation and sharing of rare disease patient data and pre-competitive research will be essential to generate improvements to this forecast,” says Rubio.

For the millions living with undiagnosed rare disease or diseases without treatment, the clock is perilously ticking as they push to raise awareness and funds.

“A lot of these folks have hope, but without seeing some action behind it, the hope kind of starts dwindling,” says Quill.

More players in the rare disease space means more opportunities to bring cures to patients who desperately need them. But still, large pharma’s growing interest in the market does not necessarily mean that industry giants will completely take over the space. Despite the attention garnered by big players, overall, 1,292 companies are developing 1,387 drugs that have received Orphan Drug Status.

“There will continue to be a big place in this industry for small companies with creative ideas,” says Coté.

About the Author

Karen P. Langhauser

Chief Content Director, Pharma Manufacturing

Karen currently serves as Pharma Manufacturing's chief content director.

Now having dedicated her entire career to b2b journalism, Karen got her start writing for Food Manufacturing magazine. She made the decision to trade food for drugs in 2013, when she joined Putman Media as the digital content manager for Pharma Manufacturing, later taking the helm on the brand in 2016.

As an award-winning journalist with 20+ years experience writing in the manufacturing space, Karen passionately believes that b2b content does not have to suck. As the content director, her ongoing mission has been to keep Pharma Manufacturing's editorial look, tone and content fresh and accessible.

Karen graduated with honors from Bucknell University, where she majored in English and played Division 1 softball for the Bison. Happily living in NJ's famed Asbury Park, Karen is a retired Garden State Rollergirl, known to the roller derby community as the 'Predator-in-Chief.'